Chapter 2 The user patient journey

KEY POINTS

Individuals who are the recipients of care should be informed of standards and guidelines available and the relevance to their care

Individuals who are the recipients of care should be informed of standards and guidelines available and the relevance to their careINTRODUCTION

Society as a whole has little understanding of Musculoskeletal Conditions (MSC) and the consequences to the individual. This can have a significant ‘knock on’ effect to the individual with joint disease particularly, as MSC may cause individuals to stop working, contributing to high levels of claims for incapacity benefit, depression and poor self esteem (Department of Health 2006). People with MSC are the second highest group claiming incapacity benefit (which, for new claimants since October 2008, is now termed Employment and Support Allowance).

For individuals with MSC (e.g. osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and back pain) the consequences of their disease, both to the individual and society, are immense (Department of Health 2006). Many individuals fail to seek medical advice despite having significant pain and disability, believing there is “nothing that can be done”. This presents challenges when encouraging people to seek medical care as they may be dissuaded by public opinion and have little encouragement from family and friends to do so (Department of Health, 2006, Oliver 2007). Recent patient surveys have identified poor knowledge and support for those with MSC in the workplace and limited educational or financial incentives for support in these areas (The National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society 2004, 2006, 2007).

THE USER-PATIENT JOURNEY – MAPPING PROJECT

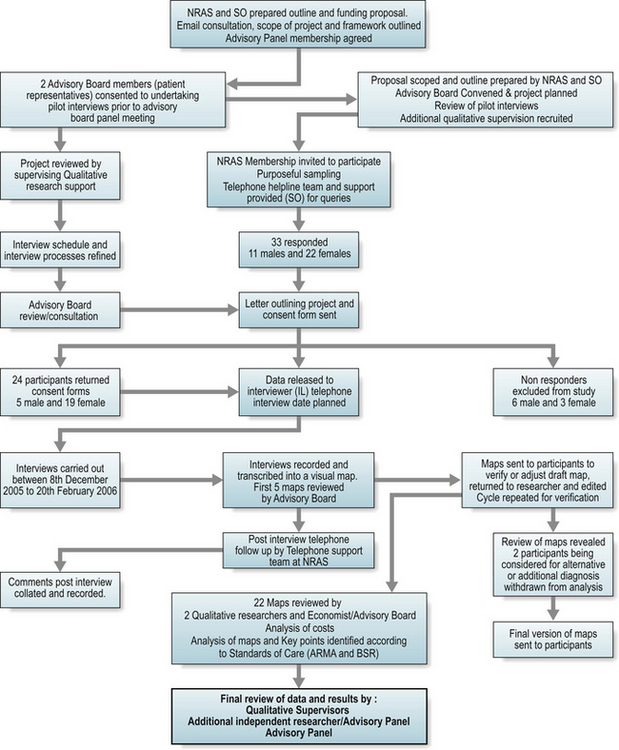

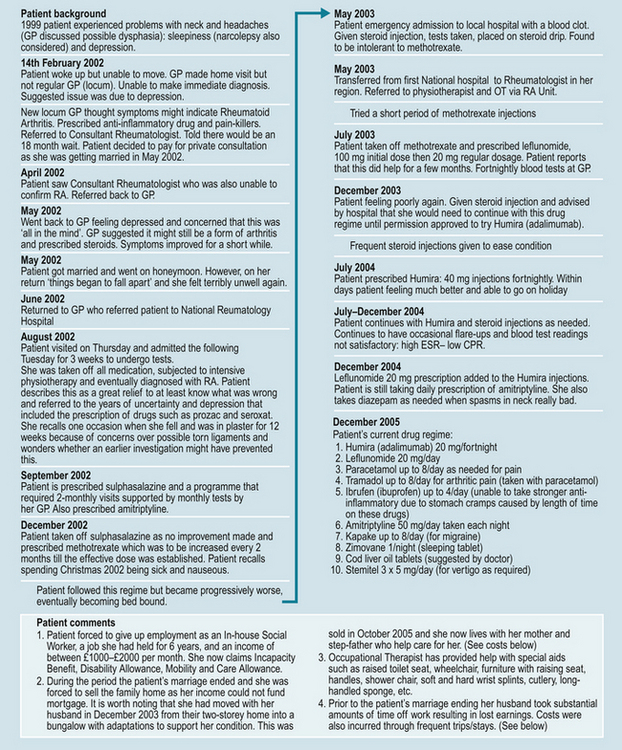

A mapping project explored the journeys of patients with early sero-positive RA. Participants were grouped into three disease duration categories ( < 1 year; 1–2 years; and > 2–3.5 years from diagnosis). The mapping project used qualitative and process mapping principles used in industry but increasingly applied to healthcare settings. Twenty-two individual patient pathways were mapped retrospectively to explore the user-patient journey and attribute direct and indirect costs to variances in care (Fig. 2.1). An example of one participant map is shown in Figure 2.2. Wide variances in many aspects of care were identified, including access to specialist services, adherence to National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance, support to stay in work and importantly, regular, patient-focussed support to enable active self management (such as telephone advice line services).

The mapping project demonstrated that indirect costs to the individual were high and borne silently (e.g. job losses). Seven of the 22 participants took early retirement or lost jobs directly due to the RA within the study period (Oliver & Bosworth 2006). These findings are borne out in other observational and quantitative research (Bone and Joint Decade 2005, Hulsemann et al 2005, Woolf et al 2003, 2004).

An additional burden is the time spent waiting to be seen by a consultant. For conditions, such as RA, early referral is essential to improve long-term outcomes. Yet, in the mapping project seven of the 11 participants seen rapidly, i.e. within 12 weeks of symptom onset, were seen as a result of private referral. The evidence collated from the mapping project is supported by other patient stories, such as those on seen on www.healthtalkonline.org, which is a registered charity describing a range of MSCs and individuals’ experiences. There are many patient stories outlined according to disease duration.

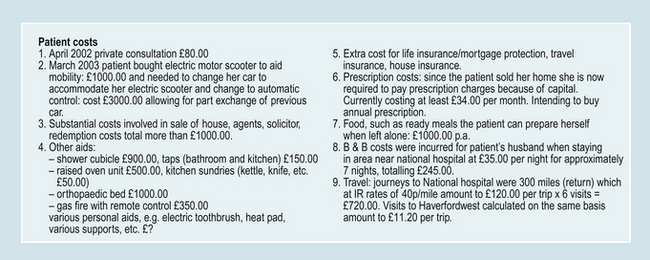

One UK study identified average annual direct costs of RA to be £3980 (Cooper et al 2002). Higher costs were associated with those who were either younger, had longer disease duration or more severe disease. A younger group is more likely to be in full-time employment and thus, additional costs relate to loss of work, extended sick leave or reduction in work hours (Merkesdal et al 2005). For example, over a three year period, delays in referral or receiving a definitive diagnosis or treatment for this group identified significant costs. Personal costs for three individuals in this project averaged £1990.27. Some of the variances in treatment costs are outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Variances in treatment and personal costs

| BIOLOGIC PARTICIPANTS | TOTAL COST TO HEALTH PROVIDER | TOTAL COST TO PATIENT |

|---|---|---|

| Patient number (disease duration). | ||

| 002 (2–3.6 yrs) | £30,836.21 | £3675.47 |

| 005 (1–2 yrs) | £1941.03 | £2150.70 |

| 007 ( < 1 yr) | £2071.78 | £3135.42 |

| 010 (2–3.6 yrs) | £21,738.55 | £11,097.00 |

| 016 (2–3.6yrs) | £24,084.21 | £8382.33 |

| 023 (2–3.6yrs) | £10,975.30 | £413.00 |

| Grand Total | £91,647.08 | £28,853.92 |

| DMARD PARTICIPANTS* | TOTAL COST TO HEALTH PROVIDER | TOTAL COST TO PATIENT |

|---|---|---|

| Patient number(disease duration). | ||

| 004 ( < 1 yr) | £304.10 | £514.00 |

| 007 ( < 1 yr) | £2071.78 | £31135.42 |

| 009 (2–3.6 yrs) | £3346.32 | £444.94 |

| 011 ( < 1 yr) | £1218.56 | £11.00 |

| 018 (2–3.6 yrs) | £727.60 | £348.50 |

| 019 (1–2 yrs) | £10,034.56 | £2937.60 |

| Grand Total | £17,702.92 | £7391.46 |

(time from diagnosis)

* DMARD = Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug

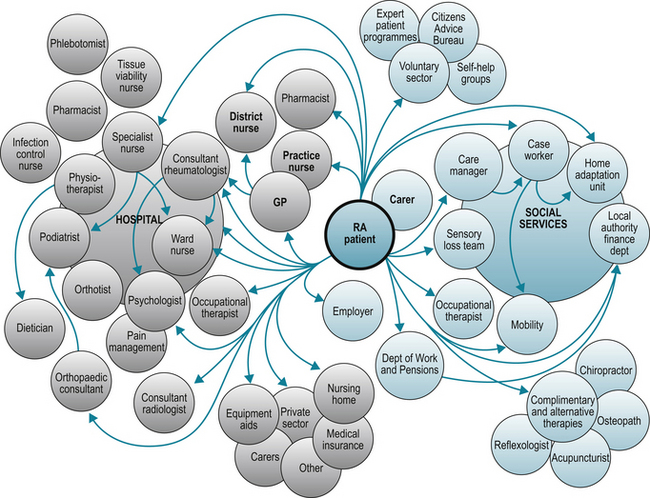

Receiving a diagnosis of a long-term condition, such as RA, is a significant life event. The social and psychological impact to the individual varies (Fitzpatrick et al 1988, Oliver & Ryan 2004). Initially, this may be because those receiving the diagnosis are unaware or unable to accept the diagnosis or that they have their own specific health beliefs or coping strategies that have an impact on their perceptions of the diagnosis and the underlying symptoms they are experiencing. Importantly however, evidence suggests that the spectrum of patient need, routes to treatment, advice and support vary dramatically (Bone and Joint Decade 2005). Indeed the various patient journeys can, as a result, be confusing and complex to map (Fig. 2.3).

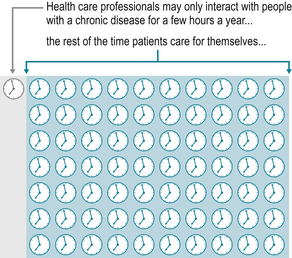

One participant (005) stated “At first the GP very helpful but I was not diagnosed at this time. The second GP good but not particularly clued up on RA and saw this as an old age disease and had no knowledge of medications being prescribed. My current GP has a specialist interest in RA which is wonderful”. For the individual, their knowledge and understanding of their condition develops over time. In some circumstances knowledge is gained from interactions with healthcare professionals (Oliver 2004). For others, the general illness experiences learnt through times of exacerbations or temporary remission, form their views and abilities on personal self management strategies (Corben & Rosen, 2005, Department of Health 2001, 2005). The reality is that people with long-term conditions manage much of their care themselves at home with their families and interact with their healthcare team for a few hours per year (Department of Health 2005) (Fig. 2.4).

There are numerous factors that affect the individual’s ability to comprehend, retain or accept the information that is provided at the time of diagnosis (Hill 2006). In addition, there are complex issues that affect the initial consultation and information giving process. Some of these include knowledge of the disease prior to seeking a diagnosis, the level of stress and pain experienced at the time of diagnosis, prior health issues, manner of communication at the time of diagnosis, personal health beliefs and the individual’s coping styles.

Education and information giving are not a one stop package but an ongoing part of care. Newly diagnosed individuals may not fully recognise this need in the early phases of the disease (Luqmani et al 2006). The variations in individual needs continue throughout their illness pathway and healthcare professionals (HCPs) need to be continually mindful of opportunities to provide information giving, education and support as and when the individual appears responsive, or requests additional information. HCPs should focus not only on the medical aspects of care but also the social and psychological consequences of disease (Arthritis & Musculoskeletal Alliance 2004, Luqmani et al 2006).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree