Chapter 16 Inflammatory arthritis

KEY POINTS

Initial detailed assessment is important in identifying where therapies can be most efficacious – opportunities for subsequent review allow timely response, especially in flares.

Initial detailed assessment is important in identifying where therapies can be most efficacious – opportunities for subsequent review allow timely response, especially in flares. Early therapy interventions minimise inflammation, pain, joint damage, deconditioning, and functional limitation.

Early therapy interventions minimise inflammation, pain, joint damage, deconditioning, and functional limitation. Self-management programmes that emphasize self efficacy and behaviour change improve health outcomes in RA.

Self-management programmes that emphasize self efficacy and behaviour change improve health outcomes in RA. Relate any exercise to improving performance of individually relevant functional tasks; individualise range, resistance, eccentric, concentric muscle work, length of hold of contraction

Relate any exercise to improving performance of individually relevant functional tasks; individualise range, resistance, eccentric, concentric muscle work, length of hold of contraction Aim to improve exercise tolerance as well as increasing range of movement/muscle strength and joint stability

Aim to improve exercise tolerance as well as increasing range of movement/muscle strength and joint stability Reassure new exercisers that joint/muscle aches may last up to 30–60 minutes after exercise – this is normal!

Reassure new exercisers that joint/muscle aches may last up to 30–60 minutes after exercise – this is normal! Dosage should be individualised – most benefit from some daily exercise (ARC, Keep Moving leaflet 2005)

Dosage should be individualised – most benefit from some daily exercise (ARC, Keep Moving leaflet 2005)INTRODUCTION

RA is a systemic, autoimmune disease characterized by symmetrical involvement of the peripheral joints, especially the small joints of the hands and feet, wrists, elbows, shoulders, knees and cervical spine. Symptoms include joint pain, stiffness and generalized fatigue, with exacerbations and remissions. Its aetiology is unknown and there is no cure. Despite significant recent improvements in medical management, RA remains a chronic condition resulting in mild to severe limitations in mobility and participation in everyday activities. RA has an impact across the spectrum of International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF: World Health Organization, 2002) (see Ch. 4). In terms of body structure and function, joint mobility, muscle function, hand strength and dexterity are frequently impaired. Activity limitations, such as difficulty walking or handling objects, may subsequently restrict participation in self care, household work, employment, social relationships and leisure. The available resources and way a person responds to their illness and the challenges it presents (personal characteristics) influences perceived health, as will the environment, such as accessibility of the physical or built environment or support provided by institutional policies. For example, work disability begins early in RA, affecting over one-third, depending on disease severity, age of onset and job demands (Burton et al 2006). RA has a substantive physical, psychosocial, and economic impact. Rehabilitation services are important in maintaining, restoring and improving patient function as well as enhancing quality of life.

CHARACTERISTICS OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

PREVALENCE AND INCIDENCE

The prevalence of RA is remarkably consistent at 0.5–1% of the population in Western nations and women are affected twice as much as men (Kremers & Gabriel 2004, Symmons et al 2002). There is a genetic susceptibility, supported by a higher prevalence in North American aboriginal populations (up to 7%) and lower rates in China, Japan and rural Africa (Ferucci et al 2004). Incidence varies but is typically close to 40 per 100,000 (Symmons 2002), although declining over the past few decades, possibly due to increased oral contraceptive use, dietary influences and cohort effects (Symmons 2002). However, a recent cohort study suggested rising incidence of RA in women after four decades of decline (Gabriel et al 2008). Mortality studies show RA decreases life expectancy, possibly due to its associated co-morbidities, including cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal problems (Kremers & Gabriel 2004). Co-morbidities may be due to chronic illness effects (e.g. de-conditioning leading to cardiovascular problems) or treatments (e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs leading to gastrointestinal problems). The increased mortality associated with RA has been relatively stable over the past few decades. Recent changes in medical management will take several years to effect mortality rates (Kremers & Gabriel 2004).

PATHOLOGY AND IMMUNOLOGY

RA is an autoimmune disease with abnormal antibody and T-cell responses to an auto-antigen (Haynes 2004). The result is a wide-spread inflammatory process in the synovial cells lining joint capsules and other body tissues, manifesting as a range of extra-articular features. The normal joint has a thin synovium lining the joint capsule. These cells produce synovial fluid which lubricates and provides nutrition to the articular cartilage. In early RA, lymphocytes infiltrate the joint capsule, proliferation of the synovial lining occurs, resulting in increased synovial fluid production. This presents as swollen, warm, red and painful joints. Prolonged periods of inflammation stress the surrounding ligaments and tendons causing laxity and subsequent joint instability. Therefore, intervention focuses on reducing the inflammatory response. In more advanced stages pannus forms: the synovium proliferates with fibroblasts, macrophages, T cells, and blood vessels. The pannus invades and erodes articular cartilage, eventually exposing the bone. Bone resorption and remodelling may occur in end-stage disease when cartilage destruction may be unavoidable. Intervention for end-stage disease is typically joint replacement.

Extra-articular features of RA include a range of inflammatory processes: cutaneous changes such as vasculitis (inflammation of the small blood vessels) and rheumatoid nodules (fibrosis nodes in subcutaneous tissue, commonly near the elbow); inflammation of tissues in the eye (scleritis, uveitis); cardiac disease (myocarditis, pericarditis and effusions); lung and pleural disease; kidney disease and peripheral neuropathies (Haynes 2004). Generally speaking, extra-articular manifestations suggest more severe disease. Therapeutic recommendations and interventions need to accommodate systemic symptoms and impairments as well as joint disease.

DIAGNOSIS, DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND SPECIAL TESTS

Diagnosis results from a careful history together with physical examination, radiological and serological tests. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) established criteria for the diagnosis of RA (Arnett et al 1988), listed in Table 16.1. Diagnosis is confirmed if a patient has at least four of the seven criteria. The first four must have been present for at least 6 weeks. Rheumatoid factor (RF) is important for both diagnosis and prognosis of RA (Shin et al 2005).

Table 16.1 Revised criteria for classification of RA (Arnett et al 1988)

| CRITERION | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| 1. Morning stiffness | Morning stiffness in and around the joints, lasting at least 1 hour before maximal improvement |

| 2. Arthritis of 3 or more joint areas | At least 3 joint areas simultaneously have had soft tissue swelling or fluid (not bony overgrowth alone) observed by a physician. The 14 possible areas are right or left PIP, MCP, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle and MTP joints. |

| 3. Arthritis of the hand joints | At least 1 area swollen (as defined above) in a wrist, MCP or PIP joint |

| 4. Symmetrical arthritis | Simultaneous involvement of the same joint areas (as defined in 2) on both sides of the body (bilateral involvement of PIPs, MCPs or MTPs is acceptable without absolute symmetry) |

| 5. Rheumatoid nodules | Subcutaneous nodules, over bony prominences or extensor surfaces or in juxta-articular regions, observed by a physician |

| 6. Serum rheumatoid factor | Demonstration of abnormal amounts of serum rheumatoid factor by any method for which the results have been positive in < 5% of normal control subjects |

| 7. Radiographic changes | Radiographic changes typical of rheumatoid arthritis on postero-anterior hand and wrist radiographs, which must include erosions or unequivocal bony decalcification localized in or most marked adjacent to the involved joints (osteoarthritis changes alone do not qualify) |

Key: MCP, metacarpophalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal

Other tests aid monitoring disease activity. Most commonly ESR and C-reactive protein (CRP) blood tests assess levels of inflammation and are known as ‘inflammatory markers’. CRP is a better indicator of the acute phase response in the first 24 hours, but a more expensive test. (See Chapter 3 for details). Raised markers often indicate a ‘flare’ of RA, but the possibility of infection causing this elevation should always be considered.

Therapists should be aware of a patient’s haemoglobin (Hb) because, not only may RA patients present with ‘anaemia of chronic disease’, but as inflammatory markers rise, Hb may fall and vice versa. Consequently, a patient with low Hb, may not be as able to actively participate with therapy; appearing pale and possibly reporting overwhelming fatigue.

MONITORING DISEASE ACTIVITY, PROGRESSION AND PROGNOSIS

Predicting prognosis is challenging, but outlook is now more positive with recent significant pharmacological advances and the advent of anti-TNF therapies (see Ch. 15). A sero-positive rheumatoid factor (RF), at, or soon after diagnosis, indicates a worse prognosis in terms of long term erosive joint disease (Shin et al 2005). Auto-antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) may be more specific than RF, not only for predicting prognosis (Kastbom et al 2004), but also diagnosing RA (Nishimura et al 2007). El Miedany et al (2008) suggest longer duration of early morning stiffness (EMS), greater percentage change in health assessment questionnaires (HAQ) and anti-CCP positivity are all predictors of persistent arthritis. Ongoing disease activity, both clinically and serologically, has been linked to increasing morbidity, loss of function and mortality. Therapists should be aware of anticipated prognosis and pro-actively target therapies accordingly.

Felson et al (1993) published a core set of disease activity measures for use in RA clinical trials. These include articular indices (joint counts), the patient’s assessment of their pain and physical function and both the patient and clinician’s global assessment of disease activity, as well as results of one acute inflammatory marker. Therapists should be aware of these valid and reliable measures, but may use them in isolation and/or combination with other functional measures of therapy progress. Twenty percent, 50% and 70% response criteria (known as ACR 20, 50 and 70) have been defined to identify improvement in RA (Felson et al 1995), which therapists should understand. The Disease Activity Score, calculated on 28 specific joints (DAS-28), is a standard approach to monitoring RA progress and drug response (Prevoo et al 1995).

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

Conventional plain film x-rays remain the most frequently used method of evaluating disease progression in RA and assisting in diagnosis (Cimmino et al 2004). Bony erosions caused by RA may be visible from a few months following symptom onset. They are found at lateral joint margins, typically first seen in the small joints of the hands and feet (Fig. 16.1). Joint spaces may also be narrowed as the thickness of hyaline cartilage of synovial joints is reduced. Osteopaenia and peri-articular osteoporosis may be seen around these small joints on x-ray, but are more accurately quantified on DEXA scans, used to quantify the osteoporosis presenting in many RA patients (Tourinho et al 2005) particularly in early inflammatory arthritis (Murphy et al 2008).

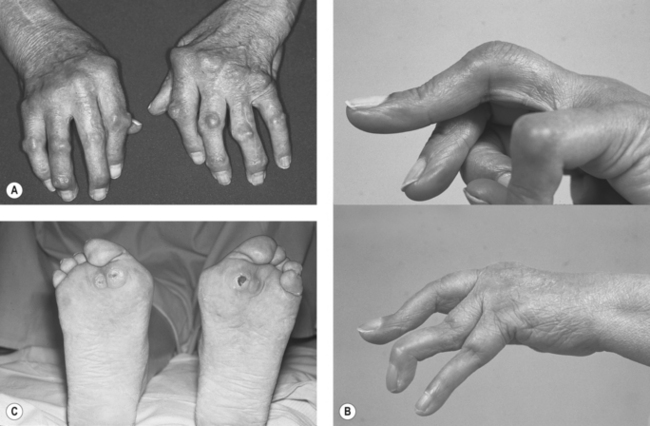

Synovial joint subluxation may also be seen on x-ray. On examination, the hands can present with deformities associated with RA: the swan-neck, boutonnière and ulnar-deviation affecting the inter-phalangeal (IP) and metacarpo-phalangeal (MCP) joints and Z deformity affecting the thumbs. Any level of the cervical spine can also be affected. The consequences of subluxation of the atlanto-axial and atlanto-occipital joints are the most serious (compression of the spinal cord, nerve roots or cervical artery). Lateral views with the cervical spine in flexion or extension help assess this as well as views of the odontoid peg from an anterior to posterior view through the mouth.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) aids evaluating synovitis, tenosynovitis and bursitis in the hands and feet of newly diagnosed patients (Boutry et al 2003). MRI may be used more in future for monitoring purposes (Cimmino et al 2004) as it is more sensitive, detecting both soft tissue and bony changes (Uetani 2007).

More recent research has focussed on using ultrasound scanning (USS) imaging in RA (Filippucci et al 2007), particularly to detect sub-clinical synovitis or bony erosions not evident with conventional radiology.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Initial assessment and ongoing evaluation will be undertaken by many multidisciplinary team members. Although overlap is inevitable, therapists have a unique line of inquiry to establish a baseline level of function, particularly related to activities of daily living, as well as identifying current clinical problems. Ay et al (2008) reported that RA patients experience most functional challenges with gripping, hygiene and grooming, running errands and shopping. For those in acute flare up, only a subjective history may be possible, perhaps with part of an objective examination. Therapists work collaboratively with patients to establish functional goals and devise plans to achieve them.

SUBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT

Drug history

The timing of medication may also be relevant, especially for patients who have recently started or stopped disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARD’s), biologics or received intra-articular injections. Knowing the timescale for drugs to reach full efficacy is important when planning therapy. See Chapter 15 for further details.

Social and functional history

This provides an understanding of the patient’s roles and responsibilities, typical daily activities and any difficulties encountered in these as a result of symptoms or joint impairment. Understanding the activities the patient needs and wants to do helps establish functional goals. Occupational performance areas should be assessed (Law et al 2005):

When problems are noted in self-care, productivity or leisure, probe for contributing factors, including pain, physical factors (strength, endurance, mobility), or environmental factors (physical barriers, lack of proper equipment for a particular task). This determines which observational assessments are necessary. Discussing social roles provides an opportunity to inquire about psychological status, such as depression resulting from withdrawal from valued activities or roles (Katz & Yelin 1994), cultural beliefs and expectations, intimate relationships or coping issues. Although not feasible to assess every area in an initial evaluation, one should be alert to those most relevant to the individual, their circumstances and stage of illness. Some may be ready to act while others may still be adjusting to the diagnosis or a change in functional status and wondering how to cope. People with more established disease may come to therapy for specific and well-delineated purposes, as they are already experienced in managing their illness.

Asking the patient to describe their usual levels of mobility (including mobility aids and if mobility level has recently changed) helps the therapist plan objective assessment safely. Ask about estimated walking distance, what limits this, e.g. pain or shortness of breath, whether steps or stairs have to be negotiated (with or without banisters/stair lifts, etc.) and corroborate ability in objective examination. Subjective evaluation may include self-report measures of health and functional status (discussed later, and in Chs 4 & 5).

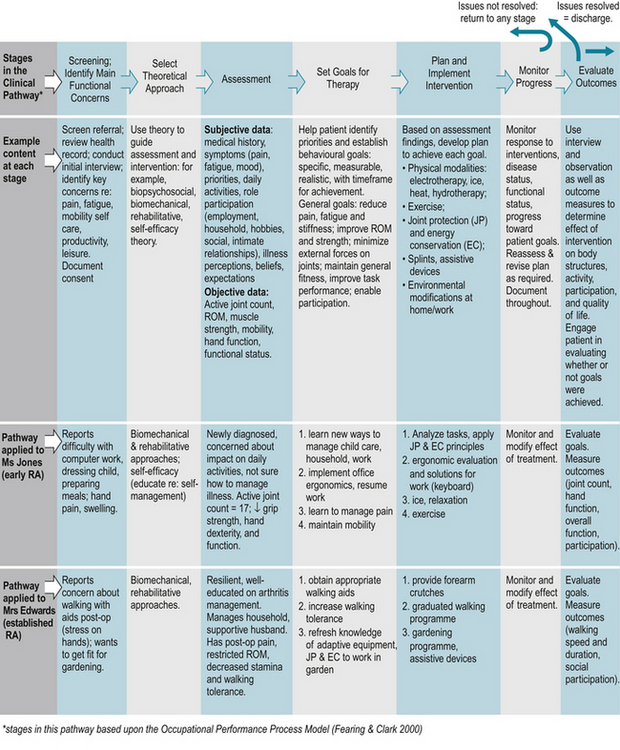

These two case examples illustrate how subjective findings will guide organizing the objective examination. The presenting issues and functional priorities differ for each patient. When time or patient tolerance is limited, focus on a few key issues for the objective examination and begin priority interventions to establish the therapeutic relationship. When necessary, evaluation and intervention planning can evolve over subsequent visits. See the clinical pathway in Fig. 16.2 for a comparison of functional goals, assessment and intervention plan for Ms Jones and Mrs Edwards.

Figure 16.2 Clinical pathway for physiotherapy and occupational therapy for individuals with rheumatoid arthritis.

OBJECTIVE EXAMINATION

If possible objective examination should follow the subjective history, but if a patient is acutely unwell, this may not be feasible. A logical approach ensures nothing of great importance should be missed if performed over several sessions. Whilst the focus will usually be the musculoskeletal system, a full respiratory or neurological assessment may be required with some patients (see Table 16.2).

Table 16.2 Components of the objective examination

| COMPONENT | DESCRIPTION | ADDITIONAL NOTE |

|---|---|---|

| General observation | Transfers, amount of assistance required, quality of movement, sitting/standing postures, eye contact | Observe patient’s response to proposed therapy, willingness to actively participate |

| UL joint observations | Swelling and/or erythema – especially MCP, IP and wrist joints | Severity of hand signs and symptoms may not correlate with poorer hand function |

| LL joint observations | Foot posture whilst weight-bearing; medial arch flattening, tendo-achilles angle, subluxation of MTP joints, tread on footwear | Document regularly used assistive, orthotic devices |

| Palpation | Small joints of hands especially but any symptomatic joints; active or inactive synovitis, tenderness | DAS-28 joint scoring adopted internationally (Prevoo et al 1995) |

| Range of movement | For UL, LL and spinal joints – measure actively and passively. Note reason for limitation of range, muscle length and neurodynamics as appropriate. | Should be linked with a functional goal Reliability of goniometry disputed: standard errors between 15 and 30° |

| Measure with manual or electronic goniometry or “eye-ball” technique | ||

| Muscle strength | Note hand dominance – power grip and key grip most functional | Jamar dynamometry and pinch/key grip dynamometry (Mathiowetz et al 1984) |

| Individual and key muscle groups should be assessed depending on functional challenges | Oxford scale method (Medical Research Council, 1976) | |

| UL – wrist extensors and rotator cuff muscles | ||

| LL – quadricep and gluteal muscle groups | ||

| Joint stability | Some agonist muscles may be a lot stronger than antagonist exacerbating instability at a joint | Key joints: wrists, MCP and IP joints in hands, knees, MTP joints and cervical spine |

| Mobility | Gait patterns +/− mobility aids and support required | Note “quality of gait” including stride length, cadence, heel strike, and distance the patient can (or cannot) walk |

| Steps/stairs | ||

| Note ability and safety | ||

| Transfers | Sit to stand, lie to sit +/− assistive devices | Make as functional and replicate home circumstances as much as possible |

| Note ability and safety | ||

| Exercise tolerance | Borg scale (Borg 1985) is a speedy and pragmatic method where patients state their “rate of perceived exertion” (RPE) | Most patients have reduced exercise tolerance |

Key: UL, upper limbs; LL, lower limbs; MTP, metatarsophalangeal, MCP, metacarpophalangeal; IP, interphalangeal

Observation

Welsing et al (2001) identified that functional capacity is most reduced with higher disease activity in early RA and with joint damage in late RA. Very often initial impressions can be deceptive; someone with apparently established and significant hand deformities may have accommodated and adapted over time and have good residual hand function. However, the opposite can also be true (see Fig. 16.3a-d).

Palpation

The DAS-28 joint scoring method identifies pain and swelling on joint palpation and is part of a disease activity score (DAS), including patient and clinician opinion, questionnaires and ESR levels as part of disease and drug monitoring (Prevoo et al 1995). Knowing which joints are most affected helps therapists to plan relevant and targeted treatment.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree