CHAPTER 6 The Technique and Art of the Physical Examination of the Adult and Adolescent Hip

The technique of physical examination

A vast number of tests exist for the examination of the hip, and it is not necessary to include them all in a single evaluation. Therefore, components of the examination can be classified as basic, which should always be included, and specific, which should be used as needed to define a specific diagnosis or combination of diagnoses. The most common examinations as determined by the MAHORN Group are shown in Table 6-1. This is a consensus among hip specialists to identify basic and specific components of the physical examination.

Table 6–1 Most Frequent Tests Performed by Mahorn Group Specialists

| Standing Position | Supine Position |

| Gait | Flexion ROM |

| Single Leg Stance Phase Test | Flexion Internal Rotation |

| Laxity | Flexion External Rotation |

| Lateral Position | FADDIR Test |

| Palpation | Palpation |

| Passive Adduction Test | FABER Test |

| Abductor Strength | Straight Leg Raise Against Resistance |

| Prone Position | Strength Assessment |

| Femoral Anteversion Test | Passive Supine Rotation |

| DIRI | |

| DEXRIT |

The standing examination of the hip

In addition to body habitus and gait evaluation, the Single Leg Stance Phase test is performed during the standing evaluation of the hip. The Single Leg Stance Phase test is performed on both legs, with the nonaffected leg examined first to establish a baseline reference for the patient’s function. As the patient lifts and holds one foot off the ground for 6 to 8 seconds, the contralateral hip abductor musculature and neural loop of proprioception are being tested. The pelvis will tilt toward the unsupported side if the musculature is weak or if the neural loop of proprioception is disrupted. Normal dynamic midstance translocation is 2 cm during a normal gait pattern; therefore, the rationale is that a shift of more than 2 cm constitutes a positive Single Leg Stance Phase test. Table 6-2 provides an outline of the standing examination.

Table 6–2 Standing Examination Associations

| Test/Assessment | Association |

|---|---|

| Spinal Alignment | Shoulder height, iliac crest height, lordosis, scoliosis, leg length discrepancy, trunk flexion and side-to-side ROM |

| Ligamentous Laxity | Check for laxity in other joints: thumb, elbows, shoulders, or knee |

| Single Leg Stance Phase Test | Proprioception mechanism disruption, strength of abductor musculature |

| Gait | |

| Abductor Deficient Gait | Proprioception mechanism disruption, weak abductor strength |

| Pelvic Rotational Wink | Contracted hip flexor, excessive femoral anteversion, laxity of the hip capsule (anterior), intra-articular pathology |

| Foot Progression Angle with Excessive External Rotation | Femoral retroversion, excessive acetabular anteversion, abnormal torsional parameters, effusion, ligamentous injury |

| Foot Progression Angle with Excessive Internal Rotation | Excessive femoral anteversion, acetabular retroversion, abnormal torsional parameters |

| Short Leg Limp | Iliotibial band pathology, uneven leg lengths |

The seated examination of the hip

The loss of internal rotation is one of the first signs of the possibility of an intra-articular disorder; therefore, an important assessment is the internal and external rotation in the seated position. The seated position ensures that the ischium is square to the table, thus providing sufficient stability at 90 degrees of hip flexion and a reproducible platform for accurate rotational measurement. Passive internal and external rotation testing is performed gently and compared between the two sides. Seated rotation range of motion is also compared and contrasted with the extended position of the hip. Table 6-3 provides normal internal and external rotation ranges of motion in these positions.

Table 6–3 Seated Examination Associations

| Test/Assessment | Association |

|---|---|

| Neurological Assessment | Symmetrical sensation of the sensory nerves originating from the L2-S1 levels, deep tendon reflexes: patellar and Achilles tendons |

| Straight Leg Raise | Symptoms of radicular neuropathy |

| Vascular Assessment | Dorsalis pedis pulse and posterior tibial artery pulse |

| Lymphatic Assessment | Inspection of the skin for swelling, scarring, or side to side asymmetry |

| Seated Piriformis Stretch Test | Deep gluteal syndrome, sciatic nerve entrapment, piriformis syndrome |

| Hip internal rotation ROM | Bilateral assessment noting any side-to-side differences. Normal between 20 ° and 35 ° |

| Hip external rotation ROM | Bilateral assessment noting any side-to-side differences. Normal between 30 ° and 45 ° |

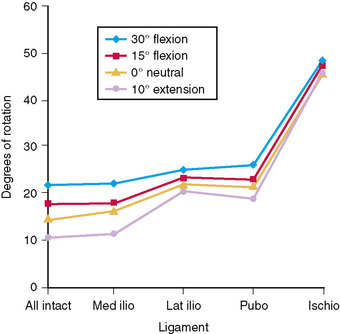

Musculotendinous, ligamentous, and osseous control of internal and external rotation is complex (Figure 6-1); therefore, any differences in seated positions as compared with extended positions may raise the question of ligamentous abnormality as compared with osseous abnormality. Sufficient internal rotation is important for proper hip function; there should be at least 10 degrees of internal rotation during the midstance phase of the normal gait. The loss of internal rotation at the hip can be related to diagnoses such as arthritis, effusion, internal derangements, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and muscular contracture. Pathology related to femoroacetabular impingement or to rotational constraint from increased or decreased femoroacetabular anteversion can result in significant differences between the sides. An increased internal rotation in combination with a decreased external rotation may indicate excessive femoral anteversion, although the hip capsular function will require further assessment; this is correlated with the radiographic findings. Table 6-3 provides an outline of the seated examination.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree