Chapter 10 The Safety and Effectiveness of Common Treatments for Whiplash

The Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders

One of the first comprehensive studies comparing the safety and effectiveness of a variety of common treatments for whiplash was performed by the Quebec Task Force. This multidisciplinary task force consisted of leading researchers and clinicians from North America and Europe and was sponsored by the public auto insurer in Quebec, Canada. The Quebec Task Force submitted a report on whiplash-associated disorders in 1995, which made specific recommendations on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of WAD. The task force’s monograph, titled Redefining “Whiplash” and Its Management, was published in the April 15, 1995, issue of Spine.1 An update was published in January 2001.2

The Bone and Joint Decade Task Force

The United Nations has declared the decade of 2000-2010 as the Bone and Joint Decade (BJD). The goal of this multinational, multi-specialty organization is to improve the health-related quality of life for people with musculoskeletal disorders throughout the world. One major project that was undertaken by the BJD was the creation of a Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. This task force published its major findings in a 250-page supplement to the journal Spine in 2008,3 and this document was republished as a supplement in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics in February 2009. Included in these publications was a comprehensive review of noninvasive interventions for the treatment of neck pain by Hurwitz et al.4 Because this task force’s report, particularly the Hurwitz et al review, is the most comprehensive and best researched summary of the risks and evidence of various commonly utilized treatments for whiplash that has been published to date, the results of these reviews will be heavily incorporated in the remainder of this chapter.

Comparing Safety and Effectiveness of Common Therapies

Common Pharmaceutical Treatments

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Although they are generally considered safe, NSAID use has been associated with a variety of serious adverse effects, including bleeding and ulcers in the stomach and intestine, stroke, kidney problems (including kidney failure), life-threatening allergic reactions, and liver failure.5

One study published in The New England Journal of Medicine6 estimated that at least 103,000 patients are hospitalized per year in the United States for serious gastrointestinal complications due to NSAID use. At an estimated cost of $15,000 to $20,000 per hospitalization, the annual direct costs of such complications exceed $2 billion. These authors also estimated that 16,500 NSAID-related deaths occur every year in the United States. This figure is similar to the annual number of deaths from AIDS and is considerably greater than the number of deaths from multiple myeloma, asthma, cervical cancer, or Hodgkin’s disease. If deaths from gastrointestinal toxic effects of NSAIDs were tabulated separately in the National Vital Statistics reports, these effects would constitute the 15th most common cause of death in the United States.

Complications from NSAID use apparently do not result only from chronic, long-term use. One double-blind trial found that 6 of 32 healthy volunteers developed a gastric ulcer that was visible on endoscopic examination after only 1 week’s treatment with naproxen (at a commonly prescribed dose of 500 mg twice daily).7

Although less common than gastrointestinal complications, kidney disease is also an infrequent but potentially serious complication from NSAIDs. One study8 found NSAID use was associated with a fourfold increase in hospitalization for acute renal failure, a risk that was dose-dependent and occurred especially in the first month of NSAID therapy.

Simple Analgesics

Simple analgesics such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) are commonly seen as being the safest and most conservative pharmaceutical treatment for WAD. In recommended doses, paracetamol (available under a number of trade names, such as Tylenol and Anacin-3), does not irritate the lining of the stomach or affect blood coagulation as much as NSAIDs. Although generally safe at recommended doses, acute overdoses (above 1,000 mg per single dose and above 4,000 mg per day for adults, above 2,000 mg per day if drinking alcohol) of paracetamol can cause potentially fatal liver damage; in rare individuals, a normal dose can do the same. Alcohol consumption significantly heightens the risk. Paracetamol toxicity is the leading cause of acute liver failure in the Western world and far exceeds all other causes of acute liver failure in the United States.9 Paracetamol is the largest cause of drug overdoses in the United States, chiefly because of the relatively narrow range between therapeutic dose and toxic dose.10 This problem is heightened by the widespread use of paracetamol together with NSAIDs and opioid analgesics in combination with pain-management drugs. Paracetamol is also used in many over-the-counter medications marketed for relief of cold and flu symptoms, migraine headache symptoms, menstrual symptoms, and other conditions.

Other Drugs

Skeletal muscle relaxant drugs, including benzodiazepines such as diazepam (Valium), are often used for treatment of acute or subacute WAD. Side effects most commonly reported were drowsiness, fatigue, muscle weakness, and ataxia. Other, less common side effects include confusion, depression, vertigo, constipation, blurred vision, hypotension, and amnesia.11

Evidence for Pharmacological Therapies

Despite the widespread use of pharmacological therapies in WAD, the evidence supporting nearly all drugs commonly used for post-whiplash pain is scanty. Hurwitz et al,4 in their BJD review, commented, “We were unable to identify any studies that evaluated the effectiveness of commonly used analgesic medications including acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and narcotics, or studies of muscle relaxants and antidepressant medications in WAD. Medications were components of the ‘usual care’ protocols in several studies, however.” There was a similar paucity of studies looking at common medications for patients with “nonspecific” neck pain (i.e., neck pain without history of whiplash).

Conservative Physical Treatments

Manual Therapies: Mobilization/Manipulation

Based on the evidence reviewed, Hurwitz et al4 concluded that mobilization was “likely helpful” for acute WAD, whereas they concluded that for manipulation there was “not enough evidence to make a determination.”

However, for nonspecific neck pain (i.e., neck pain without a history of whiplash), they found 17studies looking at various types of manual therapies and found that there was overall positive evidence for both mobilization and manipulation, particularly when combined with exercise. This led them to include mobilization, manipulation, and other manual therapies among the “likely helpful” treatments for nonspecific neck pain. However, they also found one randomized controlled trial (RCT)12 that reported that manipulation was associated with an increased risk of minor adverse reactions in patients with mostly subacute or chronic neck pain when compared with mobilization.

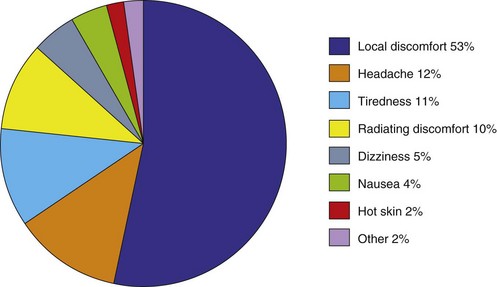

Reported complications from manipulation include sprains or strains, rib fractures, post-treatment soreness, and exacerbation of symptoms. Although these milder adverse reactions are far more common than the major complications of manipulation, they tend to be self-limiting and relatively benign in nature. In a prospective, clinic-based survey of 4,712 treatments on 1,058 new patients by 102 Norwegian chiropractors, Senstad, Leboeuf-Yde, and Borchgrevink13 found that 55% of patients reported at least one “unpleasant reaction” during the course of a maximum of six visits. The most common were local discomfort (53%), headache (12%), tiredness (11%), or radiating discomfort (10%) (Figure 10-1). Reactions were mild or moderate in 85% of patients, and 74% of reactions had disappeared within 24 hours. There were no reports of serious complications in this study.

There is a fairly widespread impression among some health professionals that chiropractic-style manipulation of the cervical spine can result in dissection of the vertebral artery and lead to stroke of the posterior cerebral circulation.14 Although recent evidence15 suggests there may be some association between a recent visit to a chiropractor for treatment of a cervical-related complaint and a subsequent stroke, the same study found a similar association between a recent visit to a primary care physician and stroke. This study suggests any association between these phenomena is due to patients with undiagnosed vertebral artery dissection seeking clinical care for headache and neck pain associated with the evolving dissection (whether that care is from a primary care physician or a chiropractor) before the dissection evolves into a stroke. The study concludes that there is likely no causal relationship between the chiropractic visit and stroke (see Box 10-1).