Chapter 7 The principles of therapeutic exercise and physical activity

KEY POINTS

Physical activity is essential for muscle, joint, general physical, psychological and social health, function and well-being

Physical activity is essential for muscle, joint, general physical, psychological and social health, function and well-being Integrated exercise and self-management rehabilitation programmes challenge erroneous health beliefs, give people active coping strategies and enhance self-efficacy, self-esteem and social interaction

Integrated exercise and self-management rehabilitation programmes challenge erroneous health beliefs, give people active coping strategies and enhance self-efficacy, self-esteem and social interactionJOINTS = MOVEMENT

The reason for having a joint is to enable us to move and so function. Joints were made to move, if we do not move our joints stiffen, our muscles get weaker, we tire sooner and control of movement is poorer. All of these can contribute to pain, disability and increase the risk of developing acute and chronic ill-health (diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, depression, obesity). Physical activity is any movement produced by skeletal muscles that expends energy (Caspersen et al 1985). Exercise is a subcategory of physical activity defined as the planned, structured and repetitive movement, to maintain or improve physical fitness (e.g. cardiovascular fitness, muscle strength and endurance, flexibility and body composition) and psychological well being (ACSM 2006). Remaining physically activity is vital for everyone and benefits our muscles, joints, general physical (respiratory, cardiovascular health), psychological (self-confidence, self-esteem,) and social (independence, social interaction) well-being.

THE IMPORTANCE OF MUSCLE

Until relatively recently little consideration had been given to the importance of muscles in rheumatic conditions, most interest concentrated on what was happening inside the joint. However, synovial joints are comprised of intra-articular (bone cartilage, capsule, etc) and extra-articular structures (muscles, ligaments, nerves). If any articular structure is dysfunctional normal joint functioning will be compromised, leading to joint damage, pain and disability (Hurley 1999).

If, due to natural ageing processes, reduced activity, injury or rheumatic disease, muscles become deconditioned (weak, easily fatigued, proprioception impaired, movement poorly controlled) then neuromuscular protective mechanisms that protect our joints will be compromised. Over time this can result in damage to cartilage and subchrondral bone, pain and disability. Importantly, this means muscle sensorimotor dysfunction may be a cause of joint damage rather than simply a consequence of it (Hurley 1999). Therefore, maintaining well conditioned muscles may enable us to maintain healthy joints, or ameliorate some of the effects of joint damage.

BENEFITS OF EXERCISE

RANGE OF MOVEMENT

Movement is vital for joint health and function as it maintains the length of soft tissues (joint capsule, ligaments, tendons, muscles), washes synovial fluid across the avascular articular cartilage bringing nutrients and removing waste, stimulates repair and reduces joint effusion (Buckwalter 1995). Therefore joints must be moved through their full range of movement (ROM) frequently to avoid soft tissues shortening, cartilage atrophying and articulating bones fusing. Maintaining joint mobility is important for everybody, but even more so for people with rheumatic conditions who are at increased risk of loss of joint mobility and consequent stiffness, pain, muscle weakness and functional limitations (Zochling et al 2006).

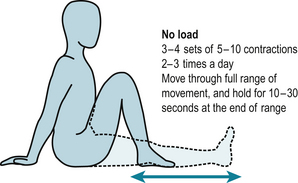

Movement can be maintained and regained by performing slow, controlled and sustained stretches at the end of ROM (Dagfinrud et al 2005). The amount of stretching done depends on how ‘irritable’ a joint is – how easily pain and effusion are provoked and if the stretching regimen has just begun. These should be performed in three to four sets of 5–10 stretches, two to three times a day (30–120 stretches in total) with each stretch held for 10–30 seconds without ‘bouncing’ (Fig. 7.1). This may cause mild discomfort, but should not cause pain.

MUSCLE FUNCTION

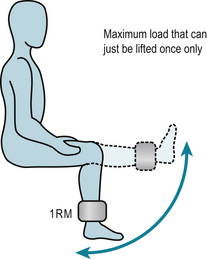

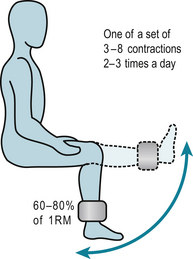

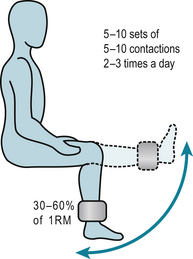

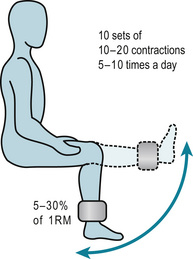

Inactivity leads to muscle weakness and increased fatigability. Fortunately, muscle has considerable ability to adapt to the loads and stresses placed on it. Specific rehabilitation regimens use the overload principle to improve muscle function. Using the load someone can lift only once through a certain range, called the 1 repetition maximum (1RM), as the reference load (Fig. 7.2) such regimens can:

FUNCTION

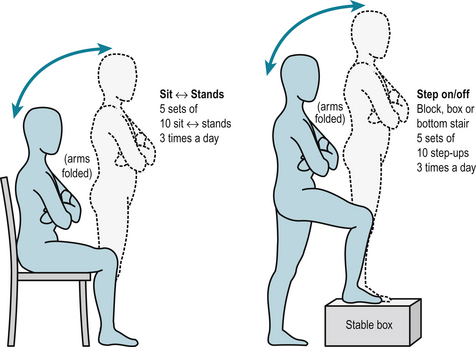

While we can address many specific aspects of muscle dysfunction with exercise regimens our ultimate aim is to help people maintain, regain and maximise functioning. Most people with rheumatic conditions want a level of muscle function that will enable them to perform their daily activities, as easily and comfortably as possible. Activities of daily living require a combination of strength, endurance and control, so exercise regimens that address muscle dysfunction must address these deficits. However, people also need to perform the activities that address their function deficits with functional activities such as sit-to-stand, steps-ups, stair climbing and balance (Fig. 7.6). These allow people to appreciate the relevance of exercise in the carry-over to easier performance of activities of daily living, maintenance of functional independence and their active involvement in their management.

FORMAL REHABILITATION PROGRAMMES

Typically, exercise-based rehabilitation is carried out in hospital out-patient departments. These regimens take various forms, but predominantly involve land-based exercises supervised by healthcare professionals (usually physiotherapists, occupational therapists, exercise therapists) who devise an individualised exercise programme to address each patient’s needs and goals, using the overload principle to increase muscle strength, endurance, joint flexibility and function. This is performed individually or in groups and supplemented with a home exercise regimen. After they have completed the regimen (usually between one and six sessions) they are discharged with advice to continue exercising, follow-up is rare (Walsh & Hurley 2005).

Reviews of research regimens demonstrate that exercise is safe and effective for people with a wide range of rheumatic conditions (Brosseau et al 2004, de Jong & Vlieland 2005, Devos-Comby et al 2006, Fransen et al 2002, Hurley 2003, Klepper 2003, Minor 1999, Munneke et al 2005, Pelland et al 2004, Pendleton et al 2000, Roddy et al 2005, Stenström & Minor 2003, van Baar et al 1999, van Tulder et al 2002).

However, often these research regimens bear little resemblance to the clinical management as they tend to be prolonged, complex regimens that require supervised use of sophisticated equipment so people become reliant on therapists. Once supervised rehabilitation stops, people’s motivation to exercise wanes, exercise ceases and the benefits are lost. To sustain benefits, patients must continue to participate in regular exercise. Given the size of the population, the chronic, long-term nature of rheumatic conditions and limited resources, the clinical applicability of many exercise regimens is limited. Clinically practicable regimens have been developed that are more likely to be deliverable to large numbers of people (Bearne et al 2002, Ettinger et al 1997, Hay et al 2006, Hurley et al 2007, McCarthy et al 2004, Thomas et al 2002).

Hydrotherapy employs water-based exercises that utilises the warmth and buoyancy of water to relax muscles and reduce the weight-bearing load and stress on our legs and trunk, but also uses water to assist and resist movement to help us exercise more effectively (Cochrane et al 2005, Epps et al 2005, Foley et al 2003, Fransen et al 2007, Green et al 1993, Patrick et al 2001, Takken et al 2003, Verhagen et al 1997, 2004). Hydrotherapy is very popular with people but requires dedicated facilities and therapists which makes it very expensive. Given the limited healthcare budgets and the large number of people with rheumatic conditions only a small minority of people will ever receive a brief, one-off course of hydrotherapy. Increasingly local community pools are organising ‘aquatherapy’ classes that provide more people with the opportunity to participate in controlled water-based exercise classes, supervised by experienced therapists at moderate cost (Cochrane et al 2005). If aquatherapy classes are not available recreational swimming and exercising gently in a local pool is an excellent way to keep stiff painful joints moving.

Tai Chi and Yoga are other less traditional ways of exercising that are popular and widely available and early small trials have found them to be effective (Ernst 2006, Fransen et al 2007), but not everyone wants to participate in these types of activities. It makes no difference where people exercise whether they exercise alone at home, in a leisure centre or join an exercise class (Ashworth et al 2005), so personal preferences can be accommodated. Although people are often reluctant to exercise in groups the additional benefit of group exercise classes is the peer support and motivating reinforcement fellow participants provide, the facilities and social interaction all of which encourages commitment to long-term exercise.

SAFETY

The first rule of any healthcare intervention is ‘do no harm’. Physical activity and exercise is contraindicated in very few people-those with advanced, serious, unstable medical conditions, and those with very deformed and unstable joints. Theoretical fears that exercise and physical activity exacerbates inflammatory rheumatic conditions (Blake et al 1989, Merry et al 1991) have not been supported by evidence. In fact in people with mild to moderate rheumatic disease exercise improves aerobic fitness, muscle strength, pain and disability following exercise programs without exacerbating symptoms, radiological damage or disease activity (Bearne et al 2002, Brosseau et al 2005, Ekdahl & Broman 1992, Minor 1999, Munneke et al 2005, Nordemar et al 1981, Stenstrom et al 1991, 1993, van den Ende et al 1998, Zochling et al 2006). It is important that physical activity and exercise is sensibly planned and not overambitious, any new activity should be started slowly, increased gradually and performed moderately (see Patient Information Sheet 7.1). As a rough guide people are exercising moderately when they can do an activity and still hold a conversation but cannot sing (the informal ‘talk test’) and vigorously when they cannot talk while doing an activity (Meldrum 2003).

People may have concerns about the safety of exercise, which need to be discussed to allay fear and anxiety. Initially, supervised exercise may be required in order to reassure people that exercise is safe and encourage them to exercise. People with severe joint malalignment might be discouraged from undertaking strenuous strengthening exercises (Brouwer et al 2007) but should still be counselled to be physically active with precautions such as little and often, using a walking stick, etc. But it should be emphasised that for the vast majority of people sensibly planned physical activity and exercise is not harmful and the benefits of physical activity far outweigh the risks of inactivity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree