The Nematodes

Thomas Cherian

The phylum Nematoda constitutes one of the six classes included in the phylum Aschelminthes. It is the second largest phylum in the animal kingdom, comprising an estimated 500,000 species, most of which are free-living. A few species are parasitic, including some that are parasitic to humans. Nematodes are cylindrical organisms, tapering at the head and tail ends. Their bodies are encased in a thick, impervious cuticle. They have a body cavity that contains the organs. With rare exceptions, parasitic nematodes have separate genders.

The life cycle of parasitic nematodes varies considerably among species. These differences have clinical significance because some infections may be transmitted directly from infected to uninfected humans, whereas in others, the eggs must undergo an obligatory period of maturation outside the human host before they become infectious to other humans. Nematodes do not multiply within humans, the exception being strongyloidiasis in the immunocompromised host.

GLOBAL IMPACT AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Nematode infections are among the most common infections in humans. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 2 billion individuals are infected by soil-transmitted helminths, namely Ascaris, hookworm, and Trichuris, worldwide, many being multiply infected with two or more nematodes. More than 300 million of these individuals suffer from associated severe morbidity and 155,000 deaths are reported annually. The numbers of people infected with Ascaris, hookworm, and Trichuris worldwide are estimated to be 1.4 billion, 1.2 billion, and 1 billion, respectively. More than three-fourths of those infected live in developing countries.

Nematodes are found most commonly in regions with warm, humid climates where malnutrition, poor living standards, and poor sanitation are common. Indiscriminate defecation and use of human feces as fertilizer are important risk factors. Nematode infections may be acquired through the ingestion of eggs (Ascaris, Enterobius, whipworm), by penetration of infective larvae (hookworm, Strongyloides), by insect bite (filarial worm), or by ingestion of infected meat (trichinella) or fish (Capillaria, Anisakis) (Table 223.1).

In areas where infection is endemic, maximum intensity occurs in school-aged children, adolescents, and young adults. This outcome is explained by age-related changes in exposure and the acquisition of immunity. Even among the high-risk section of the population, infection tends to be highly aggregated, so that a few persons harbor heavy worm burdens, although most harbor few parasites. Heavily infected individuals within a community are predisposed to this state by such as yet unidentified processes as behavioral and social factors, nutritional status, and genetic background. Heavy worm burdens in schoolchildren in developing countries directly or indirectly cause undernutrition, growth retardation, anemia, and impaired cognitive function. Many of these effects may be reversed by chemotherapy. It has been suggested that the immunologic responses to chronic helminthic infection may predispose to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and tuberculosis and impair the

efficacy of vaccines against these or other diseases. However, this effect has yet to be conclusively demonstrated. At least one recent cohort study in Uganda did not show any evidence that helminthic infection contributed to a more rapid progression of HIV infection or that antihelminthic treatment had any of effect on the CD4 counts or viral load.

efficacy of vaccines against these or other diseases. However, this effect has yet to be conclusively demonstrated. At least one recent cohort study in Uganda did not show any evidence that helminthic infection contributed to a more rapid progression of HIV infection or that antihelminthic treatment had any of effect on the CD4 counts or viral load.

TABLE 223.1. SUMMARY OF THE COMMON INTESTINAL AND TISSUE NEMATODE INFECTIONS IN HUMANS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In developed countries (including the United States), nematode infections are encountered most commonly in travelers to developing countries and among immigrants and adoptees from endemic regions. With increasing air travel and immigration, the prevalence of nematode infections in the United States is bound to increase. Infection in travelers is common, although often asymptomatic, because of the low worm burden.

INTESTINAL NEMATODES

Ascaris lumbricoides

Ascaris lumbricoides is one of the largest and most common parasites in humans. In the United States, estimates posit that 4 million people are infected, mainly in the Southeast. The adult worm is 15 to 30 cm long and resides in the lumen of the jejunum and the ileum.

Life Cycle

Infection occurs by ingestion of embryonate eggs via contaminated fingers or food or by geophagia. The adult female worm produces on average 200,000 eggs per day, which are passed in the feces. The eggs develop in the soil in perhaps 2 to 3 weeks. On being swallowed, the eggs develop into second-stage larvae that penetrate the intestinal wall, enter the venous circulation, and travel to the lungs. A local hypersensitivity reaction (Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon) may occur at the site of entry of the larvae into the lung tissue. After further development in the lungs, the third-stage larvae ascend to the trachea, are expectorated, and then are swallowed. The resultant introduction of the fourth-stage larvae into the gastrointestinal tract allows them to develop into mature adults that establish residence in the jejunum and ileum, completing the cycle.

Clinical Features

The most common clinical manifestations are nonspecific colicky abdominal pain and distension. These symptoms are caused by metabolic products of the worms, which irritate the sensory receptors in the intestine and result in interference with normal peristalsis, spasmodic contraction, and ischemia of the bowel wall.

Chronic ascariasis is known to precipitate malnutrition in undernourished children, probably as a result of malabsorption. Ascaris infection causes fat and lactose intolerance and malabsorption of vitamin A. Protein absorption is improved in children after treatment of ascariasis.

Heavy infestation with Ascaris can result in small-bowel obstruction. Migration of worms can cause obstruction of biliary and pancreatic ducts. In regions where it is endemic, Ascaris is a common cause of acute abdominal emergencies and biliary and pancreatic disease.

Migration of larvae through the lungs may result in Löffler syndrome presenting as fever, productive cough, eosinophilia, and pulmonary infiltrates.

Diagnosis

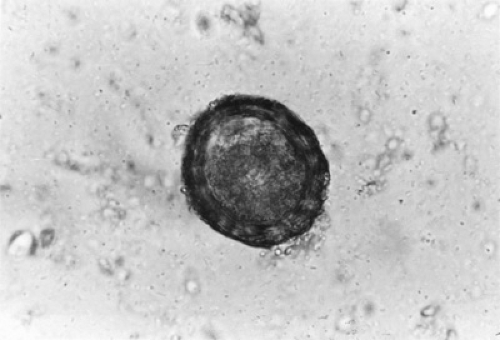

Diagnosis is made by the demonstration of the distinctive golden-coated embryonate and nonembryonate eggs (Fig. 223.1); concentration techniques rarely are needed. Sometimes,

adult worms may be passed per rectum or, less commonly, coughed up through the mouth or nose. Eosinophilia is seen during the pulmonary migration phase of the larvae but might not be seen in uncomplicated intestinal infection.

adult worms may be passed per rectum or, less commonly, coughed up through the mouth or nose. Eosinophilia is seen during the pulmonary migration phase of the larvae but might not be seen in uncomplicated intestinal infection.

Treatment

The recommended treatment for symptomatic or asymptomatic infection is pyrantel pamoate, 11 mg/kg, not to exceed 1 g, as a single dose; mebendazole in a fixed dose of 100 mg twice daily for 3 days or as a single dose of 500 mg; or albendazole in a single dose of 400 mg. Pyrantel pamoate and albendazole are approved drugs but considered investigational for this condition by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Experience with these drugs is limited in children younger than 2 years; nevertheless, these drugs do not seem to act differently in this age group as compared to older age groups.

In cases in which intestinal or biliary obstruction is suspected, piperazine citrate solution, 75 mg/kg/day, not to exceed 3.5 g, may be given through a gastrointestinal tube. Piperazine paralyzes the worms, allowing them to be passed by peristalsis without migrating into other sites. Piperazine is antagonistic to pyrantel pamoate, and the two should not be used together.

Hookworms

Infection with two species of hookworm, Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus, affects approximately 1.2 billion people worldwide. Infection was prevalent in the southeastern United States until the 1930s, but transmission has since been reduced greatly, owing to eradication programs and improved sanitation; currently, most cases are imported. In developing countries, hookworm infection is a common cause of iron deficiency anemia and hypoproteinemia. More recently A. caninum has been reported as a cause of eosinophilic enteritis in northeastern Australia.

Life Cycle

Adult hookworms are cylindrical, grayish white, and approximately 1 cm long. They reside in the upper small intestine. The adult female worm may produce 9,000 to 30,000 eggs daily, which are passed in the feces. Under suitable soil conditions of temperature and humidity, the eggs hatch into larvae, molt, and become infective. Infective larvae penetrate exposed skin that comes into contact with contaminated soil, enter the venous circulation, and are carried to the lungs. In the lungs, the larvae penetrate the alveoli, travel up the trachea, and are coughed up and swallowed. In the gastrointestinal tract, the larvae mature into adult worms that attach themselves to the jejunal mucosa, sucking minute quantities of blood. The worms change location every 4 to 8 hours, producing minute mucosal ulceration.

Clinical Features

An intense pruritus, erythema, and vesicular rash (ground itch) may develop at the site of the entry of the infective larvae. Passage through the lungs may cause Löffler syndrome–like effects, with cough, pulmonary infiltrates, and eosinophilia.

The intestinal phase of the infection results in epigastric pain, tenderness, and diarrhea. The major clinical manifestations of infection in children are anemia and hypoproteinemia as a result of chronic blood loss. The daily blood loss from a single adult worm is 0.16 to 0.34 mL for A. duodenale and 0.03 to 0.05 mL for N. americanus. Thus, moderate infection (100 to 500 worms) and severe infection (500 to 1,000 worms) can cause significant blood loss daily. Iron deficiency may lead to geophagia in young children, which in endemic areas may result in other nematode infection.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by finding the characteristic ovoid eggs in the feces (Fig. 223.2). Direct examination of the feces is sufficient with egg counts of more than 1,200 per milliliter of feces; concentration techniques may be required for light infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree