The Meniscus

Monika Volesky MD

Donald H. Johnson MD, FRCS

The importance of preserving the meniscus to protect the articular cartilage has been recognized over the past 2 decades. The original concept of the meniscus as a vestigial functionless structure has evolved to one of weight bearing, lubrication, stability, and nutrition of the articular surface.

The clinical presentation of a meniscal tear is pain and swelling following a twisting injury. The signs are joint-line tenderness, an effusion, and limited motion.

In the chronic situation, a McMurray test may be elicited to reproduce the loose meniscal fragment being trapped between the condyles. Imaging with plain x-rays is done to rule out fractures, loose bodies, or osteoarthritis. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays a valuable role in demonstrating a meniscal tear.

The indications for meniscal repair depend upon the chronicity of the tear, the size and appearance of the tear, location or zone of the tear, medial or lateral tears, and whether or not an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction will be done at the same time.

The acute treatment of meniscal tears is conservative with protected weight bearing, modified activity, ice application, and anti-inflammatory medication. Treatment is aimed at reducing the effusion and increasing the range of motion.

Operative treatment is indicated when a meniscal tear has been diagnosed and there is no improvement in the patient’s symptoms. Some stable tears may be treated with abrasion and trephination alone. Degenerative tears are usually treated by excision of the unstable fragments of the meniscus.

There are numerous methods for meniscal repair, inside-out sutures, outside-in sutures, rigid meniscal fixators, and fixators that are embedded leaving only a suture on the surface of the meniscus. Most authors consider meniscal suture to be the standard for repair. Inside-out suture repair should be done with a separate outside incision to retrieve the suture needles and avoid neurovascular complication.

The use of rigid meniscal fixators for an all-inside technique has become popular due to ease of use and reduced operative time; however, there are more potential complications, including injury to the articular surface, neurovascular injury, migration of the devices, inflammatory reaction to the implant, and failure of the repair.

The rehabilitation of the repair has been controversial in the past. Most authors restrict weight bearing flexion exercise for 6 weeks after a meniscal repair.

Outcome of meniscal repair in the short term has been reported to be satisfactory with 80% to 90% success. The results of both fixators and sutures seem to deteriorate over time. This may be due to the incomplete healing of the tears that are reported as successes in the short-term, but will fail in the long-term in this active athletic group.

The future holds improvement in the healing of the tears by augmenting the repair with growth factors. Meniscal transplantation with either collagen scaffolds or allograft tissue may also prove to be chondroprotective in the long-term.

The last 2 decades have called attention to the importance of preserving the meniscus to protect the articular surfaces of the knee. This evolution has been stimulated by the customary use of arthroscopy and the ongoing research on the natural history, basic science, and biomechanics of meniscal injury (1). Annandale (2) first reported meniscal repair in

1885, contradicting the conventional wisdom of the time, which thought menisci to be functionless remains of muscle origins (3). A rejuvenated interest in meniscal repair began when Ikeuchi (4) performed the first arthroscopic repair in Japan and published his findings in 1979.

1885, contradicting the conventional wisdom of the time, which thought menisci to be functionless remains of muscle origins (3). A rejuvenated interest in meniscal repair began when Ikeuchi (4) performed the first arthroscopic repair in Japan and published his findings in 1979.

Our understanding of meniscal function has evolved from the described “functionless” structure to the view that they are, indeed, crucial components of the normal biomechanics and functioning of the knee. Laboratory investigations have shown that the menisci participate in many important functions, including tibio-femoral load transmission, shock absorption, lubrication, and passive stabilization of the knee joint (5,6,7). Removal of meniscal tissue increases local contact stresses across the articular cartilage proportional to the amount removed. It is well accepted that total and even partial meniscectomy gradually results in radiographic Fairbank (8) changes and symptomatic degenerative changes in the knee (9,10,11,12,13,14,15). In fact, it is clear that the menisci are essential components of the normal knee, and that techniques intended to preserve the menisci are desirable. As evidence accumulates from both animal and clinical studies of the frequent development of degenerative changes following meniscectomy, surgeons have become increasingly aggressive in their efforts to conserve as much meniscal tissue as possible (5).

Injuries to the knee menisci are common and operations to treat them are among the most frequent procedures performed by orthopaedic surgeons (16). Although it was first described over a century ago by Annandale (2), meniscal repair has only regained popularity in the last 20 years. A variety of techniques for repair have been devised and there remains no common consensus among experts with respect to which treatment of meniscal lesions is best (17). The techniques of meniscal repair have evolved over time from an open suture meniscal repair to a number of arthroscopic techniques using diverse implants. Many of these devices have facilitated meniscal repair, making it more appealing to the arthroscopic knee surgeon. More difficult, however, is understanding the intricacies of all the devices available on the market, including their composition, indications for use, methods of insertion, as well as the advantages and drawbacks of each particular implant.

Cabaud et al. (18) canine and rhesus experiments with meniscal laceration and repair showed that certain meniscal tears, particularly those involving the vascular periphery, can heal and may be repaired rather than resected. Later canine experiments confirmed that the vascular healing response originates from the peripheral synovial tissues (19). Classification of meniscal vascular anatomy is based on anatomic studies that depict a peripheral vascular zone, including a synovial fringe that extends a short distance over both the femoral and tibial surfaces of the menisci, but does not contribute any vessels to the meniscal stroma (20). The “red,” or vascular, portion of the meniscus refers to the peripheral 10% to 25% of the lateral meniscus and the peripheral 10% to 30% of the medial meniscus, which is penetrated by vessels originating in the perimeniscal capsular and synovial capillary plexus (19). The central portion of the meniscus is relatively avascular, or “white,” while the watershed area between them is referred to as the “red-white” zone (21) (Fig 38-1).

The reparative process of the meniscus involves a coalescence of blood from the peripheral vascular zone adjacent to the meniscal tear and formation of a fibrin clot. Undifferentiated mesenchymal cells accumulate in the clot forming a cellular fibrovascular scar, which maintains the tear edges in a reduced position. The inflammatory reaction proceeds with ongoing invasion of cells from the “synovial fringe” and the fibrovascular scar tissue. This inflammatory cascade ultimately results in angiogenesis in the premeniscal capillary plexus allowing vessels to proliferate through the repair tissue.

Animal studies have shown that when a radial tear extends into the synovium, it can heal spontaneously by fibrovascular scar in approximately 10 weeks (19). In rabbit medial menisci, the mean scar strength 6 weeks after repair was 19% (no treatment), 26% (suture repair), and 42.5% (fibrin glue) of the value measured in the equivalent region of the intact contralateral controls (22). This inherent healing ability of the meniscus is the foundation on which clinical initiatives of meniscal repair are based.

History

The meniscus is commonly injured in sports, but can occur as a sequela of age-related degeneration. In these cases there may be no trauma, but more typically, patients give a history of a twisting injury followed by pain. This acute episode may involve locking of the knee and moderate swelling. Recurrent

episodes of pain and swelling are occasionally accompanied by complaints of mechanical symptoms such as catching, popping, or locking in the knee. The pain tends to localize along the joint line, especially with deep flexion and twisting motions.

episodes of pain and swelling are occasionally accompanied by complaints of mechanical symptoms such as catching, popping, or locking in the knee. The pain tends to localize along the joint line, especially with deep flexion and twisting motions.

Physical Examination

The patient is examined for signs of an effusion, loss of quadriceps bulk, and range of motion. Tenderness to palpation along either the medial or lateral joint line is among the most sensitive signs of a meniscal tear. The collateral and cruciate ligaments are assessed to determine whether additional injury is present. Special tests for assessing the meniscus, such as the McMurray or Apley tests, are not conclusive but can aid in the diagnosis. The McMurray provocative test is performed with the patient supine, the hip flexed to 90 degrees, and the knee in forced maximal flexion. The foot is grasped by the heel, the knee is steadied, and the joint line palpated with the other hand. As the knee is slowly brought into extension, an external rotation stress will test the medial meniscus while an internal rotation stress tests the lateral meniscus. A positive test is a pain in the appropriate joint line accompanied by a thud or click. The hallmarks of a meniscal tear are presence of an effusion, joint line tenderness, as well as a positive McMurray test (Fig 38-2).

Imaging

Evaluation of the meniscal tear should include routine anterior posterior (AP) and lateral x-rays of the knee. If degenerative changes are expected, standing views including a 45-degree flexion AP view should be performed to assess the degree of joint space narrowing. Although not clinically indicated in all patients, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays a valuable role in the evaluation of the full range of meniscal pathology including the primary diagnosis of a meniscal tear, the detection of a recurrent tear after resection or repair, and the demonstration of associated injuries and complications (23). Although it is usually not possible to identify menisci that are amenable to repair preoperatively, magnetic resonance imaging does show the relative locations of the tears and is able to determine the presence of a meniscal tear with an accuracy of over 90% (24,25). These results support reports in the literature that MRI is an accurate noninvasive technique for evaluating meniscal tears (26).

The indications for meniscal repairs continue to be refined. Prior to making a determination regarding the reparability of a meniscal tear it is necessary to consider several factors including tear characteristics such as chronicity, size and appearance of the tear, medial versus lateral location, the presence of secondary tears, and whether associated with an anterior cruciate ligament injury. Patient factors such as patient age, activity, and compliance with rehabilitation also need to be considered in the algorithm of repair. The ultimate decision to repair or resect the meniscus depends on the combination of those factors and makes each case unique. Selection of an appropriate tear for repair precedes implant selection.

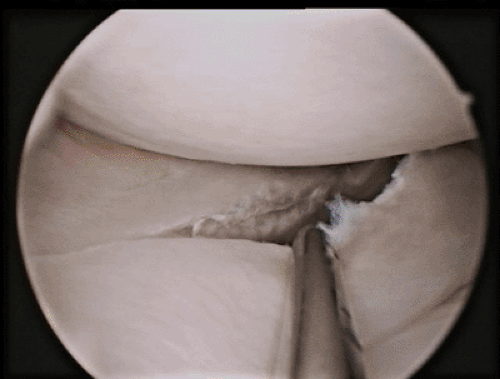

Given the vascularity of the meniscus, the peripheral, or red-red, tear is most amenable to repair, with good results also being reported in repair of tears in the red-white zone. Surgical repair of tears, which occur in the lateral meniscus, have a more favorable outcome, and thus have broader indications for repair. Short tears that are less than 2.5 cm long are easier and more amenable to repair than more extensive ones. The appearance of the meniscus is important as well, with the ideal tear being a vertical, longitudinal split. Flap, degenerative, and horizontal cleavage tears are not routinely repaired. In complex tears, all components are probed and assessed regarding the potential to heal. Rarely, all components of the complex tear are repaired, but more commonly, the central bucket handle portion is excised and the more peripheral aspects are sutured. No benefit has been shown with repairing horizontal cleavage tears, and radial tears of the middle part of the meniscus are best trimmed.

Repair of the meniscus in chronic and acute tears has long been studied, but the appearance and location remain the most important considerations. In an early study, Eggli et al. (27) found that tears repaired within 8 weeks of injury fared better, although others have found no difference in outcomes based on chronicity. Chronic bucket-handle tears will often deform with time and become difficult to reduce anatomically. Given that reduction is a prerequisite for fixing the meniscus, chronic

and deformed degenerative tears are best excised. The definition of a degenerative tear is one that shows signs of delamination, radial tears in the mid-portion of the bucket, and one that rolls when probed from the undersurface.

and deformed degenerative tears are best excised. The definition of a degenerative tear is one that shows signs of delamination, radial tears in the mid-portion of the bucket, and one that rolls when probed from the undersurface.

Special consideration must be given to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injured knee, as it is known that meniscal repairs in the ACL deficient knee have a higher failure and re-tear risk (28). Given that the ACL deficient knee is also at risk of initiating tears and propagating smaller tears, ligament reconstruction should be considered seriously for the ACL deficient patient with a reparable meniscal tear (28,29). The effect of ACL transection on meniscal strain has been studied. The meniscus, in addition to transferring force across the joint, prevents tibial displacement on the femur if the ACL is injured. With a deficient ligament there is increased anterior-posterior tibial displacement, which contributes to increased strain in the meniscus (30). Clinically, cruciate instability has been found to contribute to higher failure rates for meniscal repairs, which can be obviated by concomitant ligament stabilization surgery (31). The hematoma and resultant fibrin clot which is created while reconstructing the ACL stimulates the healing in the meniscus. Consideration should still be given to meniscal repair in patients who refuse reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament, but the patient must be counseled regarding the higher rate of failure with this approach.

There is no specific age limit for performing meniscal repair. Meniscal repairs at the time of ACL reconstruction have been described in patients up to the age of 55. Historically, most authors recommended partial meniscectomy for patients with stable knees over age 45, but acceptable results with repairs have also been reported in this age group (32,33). Most importantly, the meniscal tear must have the characteristics which allow for successful repair, without evidence of fraying or degeneration.

Certain tears have been found to heal well without meniscal repair. As a result of the biologic stimulation and stability conferred to the knee following ACL reconstruction, certain tears may be neglected when identified at the time of ligament surgery. Short, stable tears of both medial and lateral menisci in the posterior aspect of the meniscus have been found to remain asymptomatic despite lack of treatment (34) or with only trephination (35). Fitzgibbon and Shelbourne’s study (36) of 189 knees at follow up of one to nine years, confirms that certain lateral meniscal tears identified at the time of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction can be left without removal or repair, and that they will remain asymptomatic. Specifically, posterior horn avulsion tears, asymptomatic vertical tears totally posterior to the popliteus tendon, and other complete and incomplete lateral meniscal tears (vertical longitudinal, radial, or anterior vertical), if stable at the time of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, can be left in situ without becoming clinically symptomatic. In a study by Shelbourne and Rask (37), over 94% of stable peripheral vertical medial meniscus tears treated with abrasion and trephination remain asymptomatic without stabilization. Talley and Grana (38) concluded that although stable lateral meniscal tears healed well with only synovial abrasion, stable longitudinal medial meniscal tears have a higher propensity to fail over time by propagation of the tear, and may be better managed with meniscal repair.

In summary, the ideal reparable tear is a vertical one of the lateral meniscus, which occurs in the peripheral 3 mm of the red-red or red-white zone, and is being repaired with concomitant ACL reconstruction (Fig 38-3).

Nonoperative

Meniscal tears are initially treated symptomatically with protected weight bearing, modified activity, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs). Some meniscal tears will become asymptomatic after several months of these interventions. The best activity for the patient during this period is to use the stationary bicycle and to avoid deep or full squatting exercises. If the patients are willing to modify their activities and have full motion and no pain or swelling, then conservative management of the tear may be successful. A locked knee, however, usually represents a displaced bucket handle tear and will need surgery acutely to restore motion.

Operative

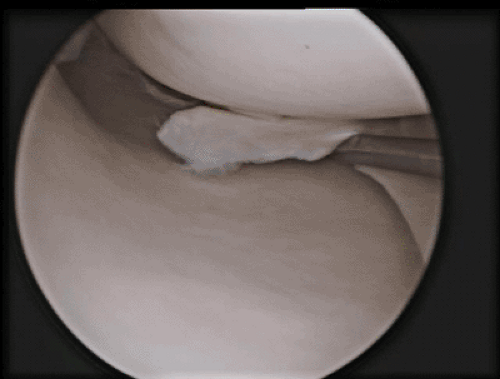

If the patient continues to have pain, swelling and giving way, then operative intervention is indicated. If there is a degenerative flap tear, then meniscectomy is the only treatment (Fig 38-4). The principle of menisectomy is to remove any unstable fragments of meniscus, to contour the edges, and to trim the remaining rim so that it is stable to probing. If,

however, the meniscal tear is amenable to repair, this can be accomplished by means of various techniques and implants. The four major methods of repairing the meniscus are: open, arthroscopic outside-in, arthroscopic inside-out, or an arthroscopic all-inside technique. Prior to the widespread use of arthroscopy, open repair techniques were performed, but arthroscopic inside-to-outside approaches evolved to decrease the morbidity and enable access to areas that are difficult to reach with an open approach. An outside-to-inside approach was later popularized, as it minimized the risk to posterior neurovascular structures. Eventually, an all-inside technique for posterior horn tears was developed which obviates posterior capsular exposure, further reducing neurovascular risk. The following sections enumerate the advantages, indications, contraindications, complications, and results of each.

however, the meniscal tear is amenable to repair, this can be accomplished by means of various techniques and implants. The four major methods of repairing the meniscus are: open, arthroscopic outside-in, arthroscopic inside-out, or an arthroscopic all-inside technique. Prior to the widespread use of arthroscopy, open repair techniques were performed, but arthroscopic inside-to-outside approaches evolved to decrease the morbidity and enable access to areas that are difficult to reach with an open approach. An outside-to-inside approach was later popularized, as it minimized the risk to posterior neurovascular structures. Eventually, an all-inside technique for posterior horn tears was developed which obviates posterior capsular exposure, further reducing neurovascular risk. The following sections enumerate the advantages, indications, contraindications, complications, and results of each.

A variety of implants to address meniscal tears are commercially available to the arthroscopic surgeon. These include absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures, bio-absorbable arrows, tacks, and staples, as well as a number of repair-stimulating techniques such as trephination, rasping, and implantation of a fibrin clot. Most authors who advocate the use of sutures utilize nonabsorbable sutures. By providing longer lasting and more stable fixation, nonabsorbable sutures are believed to allow more complete remodeling of the meniscal repair tissue, which allows for improved healing rates (27). Menisci repaired with permanent sutures also had a lower incidence of clinical symptoms and a much lower failure rate (39).

Patient Position and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

Patient positioning must allow circumferential access to the affected knee during meniscal repair. The leg should be prepped and draped to allow posteromedial and posterolateral incisions should they be required (Fig 38-5). This can be done with the patient supine such that the break in the table is at the level of the tourniquet and can be flexed down to allow 90 degrees of knee flexion. Alternatively, a leg holder can be used that allows the surgeon to abduct the leg away from the operating table, allowing the knee to flex as needed for access. Diagnostic arthroscopy is performed using a 30-degree arthroscope and includes an evaluation of both menisci, the articular cartilage in the knee, and the cruciate ligaments. The menisci are probed on the inferior and superior surfaces to identify any tears. In assessing meniscal stability, it is important to realize that the lateral meniscus is normally more mobile than the medial meniscus (40). The definition of an unstable meniscal tear is one that is longer than half the length of the meniscus, and subluxes under the condyle when probed with a hook. Although a tourniquet may be used to improve visualization during the procedure, some surgeons prefer to leave it deflated for the diagnostic arthroscopy in order to assess the vascularity of the meniscal tear after rasping.

Repairs of the medial meniscus are usually done in some degree of extension, depending on the location of the tear, to allow for adequate visualization and access. On the lateral side, the greatest visualization is obtained with the knee flexed and the leg in the figure-of-four position. This position is also key in protecting the peroneal nerve, which lies posterior to the biceps femoris tendon and furthest from the joint capsule with the knee in flexion.

The Posteromedial and Posterolateral Incision

If performing an inside-out or outside-in repair of the meniscus, a “safety” incision is usually done on the appropriate side with the knee in flexion. In the inside-out technique,

the incision is done just distal to the joint line, since the needles are passed in a cranio-caudal direction.

the incision is done just distal to the joint line, since the needles are passed in a cranio-caudal direction.

On the medial side, a 2 to 3 cm skin incision is performed posterior to the medial collateral ligament and then the fascia along the anterior border of the sartorius muscle is incised. The sartorius is retracted posteriorly, which protects the saphenous nerve and vein lying deep and towards the posterior border of the sartorius. Care should be taken to watch for the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve, which penetrates the sartorius becoming superficial to the fascia near the joint line. With blunt dissection the interval between the posteromedial capsule and the medial head of the gastrocnemius is opened, just proximal to the semimembranosus tendon.

On the lateral side, the surgeon identifies the joint line, the lateral collateral ligament and the fibular head. With the knee at 90 degrees of flexion, an incision may be made posterior to the iliotibial band, again extending 3 cm distal from the joint line. This approach can then be continued with blunt dissection passing between the anterior aspect of the biceps femoris and the posterior aspect of the iliotibial band. If the superior lateral geniculate vessels are encountered, they can be coagulated. The biceps femoris is retracted posteriorly, protecting the peroneal nerve, which lies posterior and medial to the biceps tendon at this level. The lateral head of the gastrocnemius is identified and the dissection proceeds between the gastrocnemius and the capsule, where a retractor can be placed during the passage of sutures.

Preparing the Meniscus

The tear should be initially probed to determine if it is suitable for repair. The edges of the tear should be debrided of fibrous tissue with a rasp or a small shaver. Abrasion of the menisco-synovial junction is also believed to improve the rate of repair regardless of repair method (41,42). Animal studies in rabbits have shown that rasping a meniscal surface to repair a tear in the avascular zone stimulates vascular induction to the tear, resulting in meniscal healing. The cytokine network on the rasped meniscal surface appears to be the key to explaining the mechanism of vascular induction and meniscal healing by meniscal rasping (43). A technique of stimulation of the meniscal synovial border with electrocautery has been described by Pavlovich (44). The principle is to lightly “burn” the synovium to produce a healing response. Zhongnan et al. (45) demonstrated that the meniscus and the rim may be trephinated to produce vascular access channels. Trephination involves the creation of vascular access channels by removal of a core of tissue from the periphery of the meniscus adjacent to the tear, thus connecting the avascular portion of the meniscus to the peripheral blood supply. Zhang (46,47) continues to champion the technique, and has shown increased healing rates and decreased symptoms when trephination is performed during repair. Some authors believe that for symptomatic stable or incomplete meniscal tears, trephination without suturing may be sufficient, and have shown good results while avoiding the complications associated with suturing (35,37).

Other techniques of biologic augmentation have been devised to improve healing rates. Arnoczky et al. (48) was the first to show that meniscal healing in the avascular zone of canine menisci can be enhanced by the use of a fibrin clot. Clinically, there have been favorable results with use of fibrin clot in repair of red-white meniscal tears (42,49,50,51,52). The technique involves withdrawal of 30 to 40 cc of the patient’s blood by venipuncture, which is then placed in a sterile glass container and stirred with a glass rod for a few minutes until a well-organized firm fibrin clot is formed (51). After rinsing the clot in sterile saline to remove serum and red blood cells, it is tied to a previously placed repair suture that has been brought out of an anterior portal by means of a cannula. A probe can be used to position the clot between the meniscus and the tibia as the sutures are tensioned (53).

The sutures and bioabsorbable devices must be placed accurately to reduce the tear and hold it until it is healed. A common approach to large bucket handle tears is to use sutures in the middle segment to reduce and hold the bucket tear, and then use the bioabsorbable devices posterior horn region because it is more difficult to access and repair. In summary, for good results in meniscal repair, the principles of meniscal repair, namely that stimulation of circulation and proper reduction of the meniscus must be adhered to.

Open Meniscal Repair

Indications for open meniscal repair at the present time are somewhat limited. It could be used for very peripheral meniscal tears, such as meniscocapsular separation. In reality, the repair is performed open only in special circumstances, such as multi-ligament reconstruction after knee dislocation, and at the time of tibial plateau fixation.

A 3 to 5 cm incision is made longitudinally over the joint line and vertical sutures are placed from the capsule into the meniscus.

Inside-Out Repair

The arthroscopic inside-out suture repair originally described by Henning and Lynch (9) remains the gold standard by which other techniques are judged. A major advantage of this technique is its versatility, its ease of use, and the short learning curve. Excellent healing rates have been widely reported in the literature (54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64). The Zone-Specific method of inside-out meniscal repair was popularized by Rosenberg (63) in 1986, when he developed a single-lumen cannula system (Linvatec, Largo, FL) through which sutures could be passed to repair the meniscus. The system includes single-lumen cannulae with six different curvatures that allows the surgeon to direct the tip more easily to the left or right, as well as toward the

anterior, middle, or posterior part of the meniscus. The cannulae have a 15-degree curve upward, which allows the cannula to be apposed against the meniscus and allows the needle to be passed parallel to the joint line from a slightly elevated portal. The shapes of the cannulae allow placement of the device around the tibial spines and femoral condyles, and direct the needles away from the important posterior neurovascular structures.

anterior, middle, or posterior part of the meniscus. The cannulae have a 15-degree curve upward, which allows the cannula to be apposed against the meniscus and allows the needle to be passed parallel to the joint line from a slightly elevated portal. The shapes of the cannulae allow placement of the device around the tibial spines and femoral condyles, and direct the needles away from the important posterior neurovascular structures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree