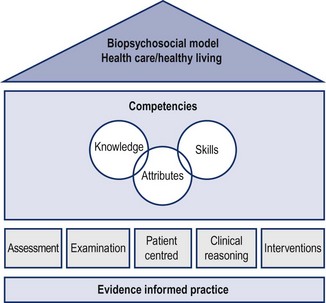

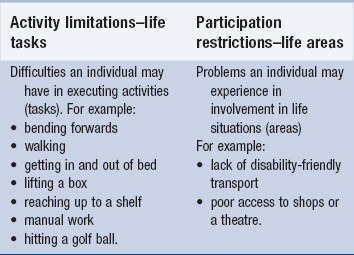

1 The equivalent within the Maitland Concept ( Maitland 1991) is that manipulative physiotherapists should be driven to: Clinical reasoning refers to the decision-making process by which the clinician can safely and effectively THINK, PLAN, EXECUTE to PROVE. Effective clinical reasoning requires the clinician to consider all aspects of theoretical knowledge and research that may be relevant to the individual patient and all aspects of clinical evidence from examination and effects of treatment (Jones et al. 2006a, 2006b). By reasoning in action the clinician can apply knowledge and skills appropriately, leading to a desired outcome of intervention and by reasoning on action there can be a reflection and analysis of what has taken place in order that further or future management can be more effective. International standards of manual therapy practice are determined by the International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists (IFOMPT) through the federation’s educational standards committee ( Beeton et al. 2008). The committee has identified 10 dimensions each with associated competencies of knowledge, skills and attributes. These competencies serve to ensure effective and expert practice in the speciality of manipulative and movement therapy. The assurance of quality standards also enhances the recognition of physiotherapy as a profession that can sustain itself autonomously within a defined scope of practice and through collaborative work with other health professions and governmental organizations. It is recognized that health professions such as physiotherapy operate most effectively within a bio-psychosocial paradigm rather than the traditional biomedical model of health care delivery ( Bazin & Robinson 2002). This paradigm shift within the profession has taken place over the last 10–20 years and has opened up many avenues for professional development. Diagnosis and a pathological basis for patients’ signs and symptoms are still very important, yet understanding the impact and health consequences of illness, disease or injury can have a profound effect on an individual’s capacity to live a healthy life. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) ( WHO 2001) is an ideal model on which to base an understanding of patients and their problems. The patients’ experiences can be evaluated from both a biological perspective and in the context of potential psychological and social factors. The physiotherapy domain therefore is changing with the paradigm shift to one where the focus is at the health care/healthy living interface and where the physiotherapy profession has a greater role to play in public health and healthy life expectancy by advocating movement and exercise as a means to ensuring the adding of life to years ( Middleton 2008). • The patient and healthy living • Analyzing the patient’s individual illness experience • Patient inclusion and participation in decision making • Patient-centred communication • Understanding the body’s capacity to inform and adapt The key requirement, therefore, of patient-centred practice is to address individual’s physical and mental well-being in order that they can function effectively, without deficit, in their daily life tasks and life areas ( WHO 2001) ( Table 1.1). The ultimate outcome of interventions of manipulative physiotherapy should be to ‘add life to years’ ( Middleton 2008). The role of physiotherapy in maximizing movement potential is the key to promoting healthy living, functional capacity and physical fitness ( Chartered Society of Physiotherapy 2008) ( Box 1.1). The physiotherapist should always start by asking the patient question 1: Secondly the patient should be asked question 2: • The patient’s perceptions and experiences (bio-psychosocial hypothesis). For example, I am worried that I may not be able to do my job properly. • The kind of disorder (pathobiological hypothesis) ( Jones et al. 2006a). For example, Adhesive capsulitis causing painful and stiff shoulder movements. • The patient’s symptoms (impairment hypothesis). For example, It is too painful for me to put my hand behind my back and too stiff to get things down off shelves at work. • The impact of the disorder on the patients’ life areas and life tasks (activity limitations, participation restrictions). For example, I struggle to get dressed in the morning. I cannot sleep on my right side. I have had to stop playing badminton. • Contributing factors (the cause of the cause).For example, I don’t think my shoulder problem is helped by the stiffness in my neck and spine since a car crash eight years ago. • Ideas about management and treatment interventions. For example, pain modulation of shoulder joint pain, mobilization of a stiff joint and prevention of adaptive shortening due to protective/adaptive posture and movement. Address contributing factors in the neck and spine. • Need for caution. For example, factors which may mediate ideal treatment. Such as cardiac capacity for exercise, medication effects on tissue viability (long-term steroids). • Thoughts about prognosis. For example, evidence from literature which supports the natural history and shapes the extent of intervention. Knowing that frozen shoulder has a self-limiting natural history of two years (plus) helps in making decisions about expectations for interventions. • Patient-reported problems – Question 1/the main problem: I am having increasing difficulty reaching to put my socks on in the morning due to groin pain and stiffness in my hip joint. • An attention to detail as to what the patient is experiencing and where (body chart): deep, intermittent ache within the groin, ache radiating down the front of the thigh to the knee. • How the problem is affecting them in their everyday life (their functional performance): every morning I struggle to put my socks on. I can only just reach the end of my foot with a lot of effort. My hip feels very stiff and sore in the groin. I have stopped playing five-a-side football because of the soreness afterwards and restriction during play. • Their tolerance and acceptance of movement and activity (severity, irritability): becoming severe as they start to avoid activities and recreation. Less irritable as symptoms settle quickly after activity. • What may be mediating their responses: fear of disability leading to surgery, frustration, anger and depression at not being able to do things ( Ashby et al. 2009). • Their C/O and P/E asterisks: (emphasis on individual, specific and utility outcome measurement) ( Box 1.2). • Health and medical issues compounding their problems: Type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for peripheral vascular disease and neuropathy. • The pathobiological nature of their condition (history) pattern: osteoarthritis of thhe hip (OA hip). • Their physical status and functional capacity: hip flexion 85 degrees stiff ++ (1) 5/10 (VAS – visual analogue scale). • Their physical capacity against ideal (impairments): reduced range of movement in the hip, weakness in hip muscles. • Risk factors to conditioning: poor general health and quality of life issues (social deprivation), access to support and socioeconomic priorities all contribute to compliance with healthy living options ( McLean et al. 2011). • Their body’s capacity to inform (movement as a therapy and pain killer): understanding the health and pain-modulating benefits of movement and exercise coupled with an appreciation of individual movement capabilities and deficits. • Their responsiveness and motivation to change: responders or non-responders to manipulative and movement therapies. This can be mediated by a number of extrinsic (personal and environmental) factors and intrinsic factors (pathobiology and nature of the problem). • Their evaluation of responses to interventions: recognition of changes in symptoms and signs during and between sessions. The primacy of clinical evidence supported and informed by research and experience-based knowledge, therefore, drives this patient-centred approach. For example, Sims (1999a) identified that in patients with OA hip X-rays reveal a common occurrence of down-and-in and up-and-out migration of the head of the femur. This knowledge may well support the clinical response of increasing range of hip flexion in such patients when lateral or longitudinal caudad mobilizations are performed at the hip (Sims 1999b). Patient-centred practice enhances the evidencing of movement impairment and functional deficit. It confirms the presence of functional pathology ( Stucki & Grimby 2007). It supports the application of appropriate interventions ( Darzi 2008) and successful patient-focused outcomes where, for example, the patient can walk without pain, they feel better in themselves and their ability to do more is evident. Errors in communication, however, are known to have a big impact on the accuracy of clinical decisions ( Maitland et al. 2005). As the physiotherapist tries to develop a broad and deep understanding of what is going on with the patient using thoughtful communication strategies ( Higgs & Jones 2000), the role of manipulative and movement therapies should be considered. Understanding the patient’s experiences will serve to make treatment decisions relevant and appropriate to individual problems. • Reasoning behind the question to be asked: (sufficient theoretical and clinical knowledge). For example, the patient is complaining about elbow pain which is sensitive to light touch. This suggests allodynia which is often associated with nerve injury. A common source of nerve entrapment is in the cervical spine so… • Wording the question: (what the therapist needs to know.) For example, to explore the possibility that the elbow pain has a neuropathic element to it I must ask the patient: ‘Have you had or do you ever have any problems with your neck?’ • Hearing and understanding the words used in the patient answer: (follow up questions to be certain of the meaning). For example, the patient has told me that his elbow started hurting in the spring. A key word here is ‘spring’ so I must find out what is the association between his elbow pain and spring. I must ask him ‘What was it that made your elbow start hurting in the spring?’ • Interpreting the answer: (clarifies the answer to understand the patient’s symptoms rather than forming assumptions). For example, the patient has told me that he had to dig over his allotment in the early spring but has never had problems before. I could assume that the amount of digging was more than usual but should qualify my question if this was the case. I must ask ‘What was unusual about the digging this year?’ The patient told me that he had had to dig an area which had not been dug before and this was very rocky. He felt the jarring rather than the amount of digging had caused his pain. • Relating the answer to the question: (has the question been completely answered in sufficient depth?). For example, in response to the question ‘Do you ever have problems with your neck?’ the reply ‘No, not now’ demands further explanation to determine whether any past episodes of neck pain could relate to the onset or development of the elbow pain. • Determining the next question: (sufficient theoretical and clinical knowledge on which to base the next question irrespective of accuracy of patient answer). For example, to understand the significance of the neck problem, therefore, the immediate response question might be: ‘When was the last time you had problems with your neck?’ • Hearing and understanding the question: (avoid using words which the patient cannot understand and avoid using questions which are biased towards a particular answer). For example, I want to use the same words that the patient uses in my follow-up questions and I want to avoid using leading questions. So I will not ask. ‘Is it right that the spondylosis in your neck was set off by the digging and this is sending pain into your elbow?’ Instead to ensure the patient understands the question and it is not leading him to a particular answer, (my hypothesis), I will ask, for example, ‘Do you feel your neck pain is connected to your elbow pain in any way?’ • Considering the reply: (the patient’s thoughts will affect what the question means to them and their memory of facts may be incomplete or inaccurate). For example, I must make sure that the question I ask does not have a double meaning and is not ambiguous. I must also be sure that I use key words to prompt the patient’s memory so that their recollection of events and experiences is as accurate as possible. So I will not ask ‘Where did you feel your first pain?’ as the patient might wonder whether I mean his neck or elbow or he might think I mean to find out whether he first felt pain at the allotment or at home. I will ask instead ‘When you jarred yourself digging in the rocky area can you recall what you felt?’ • Putting the answer into words: (be aware that the patient may lack experience in the health care environment which may influence the response given). For example, I want to ensure that the patient has every opportunity to say what they are feeling and thinking rather than what they think they are expected to say. So I will not ask: ‘What did your doctor say was wrong with you?’ Instead I will ask: ‘What do you feel happened to you when you jarred yourself whilst digging?’ Another feature of patient-driven clinical decision making is an understanding of the body’s capacity to inform (about the experience of injury, neuromusculoskeletal conditions and disease) ( Box 1.3) and adapt (influences of injury, disorder or disease on neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) functioning). If these capacities are understood then they open up a vast array of possibilities in: • Being able to understand the patient experience, and • Being able to choose interventions which relate to those experiences. An understanding of the patient’s body’s capacity to inform or adapt begins immediately the therapist meets the patient and observes them. Examples of the body’s capacity to inform and adapt and therefore drive decisions are: • The patient’s main problem: a reflection of the whole experience (for example, a knee medial ligament sprain and how it impacts on the patient’s everyday life). • What, for them, would be a successful outcome?(For example, the patient is looking forward to experiencing no pain and discomfort in the knee and being able to return to playing football as soon as possible). • The body chart: an expression of what the patient feels and how this is processed into symptoms (for example, soreness over the ligament, under the skin but sore to touch and intermittent pain). • Behaviour of symptoms: what the patient can and cannot do because of their symptoms is a reflection of how the body informs and processes what activities and participation it is capable of based on the patient’s own knowledge and frame of reference from previous experiences (for example, a sharp pain over the knee ligament when twisting the leg means that the patient avoid twisting movements because they are too painful and it feels like the ligament will break). • History of symptoms: if an injury causes or predisposes to symptoms, the body informs the patient about what has been damaged and by how much. Whether the body can help to identify a link between injuries and symptoms or not is another feature of the body’s capacity to inform (for example, the patient knew something had torn as soon as he was tackled from the side playing football last week. It hurt like a torn ligament and it swelled up almost straight away). • Medical screening questions: usually the patient knows whether they are well or not, so questions about general health and well-being will help to inform about any personal mediators which may impact on the body’s response to physical therapies (for example, the patient feels well in himself, just a bit angry at the other player. He says that he does take steroids to bulk up in the gym). • Observation: recognition of protective posture is a reflection of the body’s capacity to adapt to painful situations (for example, knee held in 10 degrees of flexion in standing). • Asking the patient to move to the first onset of pain (P1) or to the limit of available movement: this will be a reflection of the body’s capacity to inform about what is restricting movement (for example, knee extension minus five degrees due to pain and apprehension). • Asking the patient to show a functional movement, which is affected by symptoms (functional demonstration), gives the patient an opportunity to use the body’s capacity to inform about how and how easily symptoms can be reproduced and it also gives the therapist an opportunity to analyze movement with reference to possible therapeutic interventions ( Banks & Hengeveld 2010). (For example, twisting the knee causing immediate pain and apprehension.) • Structural differentiation is, in effect, the body’s capacity to inform about tissue responses to movement and which tissues to influence therapeutically (for example, stabilization of the tibiofemoral joint during the knee twisting eliminates the pain and apprehension). • Passive testing of joints, muscle length and neurodynamic capacity, helps the therapist to understand how the body reacts to passive movement (for example; tibiofemoral anteroposterior accessory mobilization grade II, which is soothing; quads lag present due to inhibition; saphenous nerve length test not painful). • Palpation: again is the body informing the therapist about tissue responses to handling and can it inform decisions about which interventions may be more effective? (For example, swollen, thickened medial ligament of the knee.) • Assessment strategies also tap into the body’s capacity to inform about responses to interventions during and after treatments have been carried out (for example, since the mobilization, the pain is not so sharp when the patient twists his knee). • Decisions to stop treatment are often based on the patient’s feedback on whether interventions have been effective. This is often informed by the body’s capacity (for example, the patient can run and jump on the knee after several sessions; it still aches a bit but he thinks it has healed and he just needs to get fit again). Collaborative reasoning is defined as the nurturing of a consensual approach towards the interpretation of examination findings, the setting of goals and priorities and the implementation and progression of treatment ( Jones et al. 2006a). Collaborative reasoning ( Jones et al 2006a) gives the therapist a framework which utilizes the body’s capacity to inform. Semistructured interviews give the patient an opportunity to impart information that is meaningful to them as individuals. Thoughtfulness in shaping semistructured questions will enhance collaboration between patient and therapist in coming to the correct (safe and effective) decisions about interventions. Examples of semistructured interview questions for the therapist to consider are: • What is the problem you are having? • What are you feeling and where? • What effect is this feeling having on your everyday life? • What seems to change the feeling you have? • How did this feeling first start? To have a patient-centred meaning, collaboration should permeate all the therapeutic processes below: • Information gathering during the subjective examination. • Planning the physical examination – the aims of the physical examination. • Determining what to examine and by how much – identify the source of the symptoms, the cause of the source and contributing factors. • Choice of interventions – what are the desired effects? • Decisions on progression – what will produce graded improvements? • Feedback on effects of interventions – what does the patient think? • Outcomes meaningful to the patient – has the outcome achieved its goal? Clinical reasoning, therefore, is a process in which the therapist, interacting with the patient and significant others (e.g. family and other health care team members) structures meaning, goals and health management strategies based on clinical data, patient choices and professional judgement, knowledge and skills ( Higgs & Jones 2000). Clinical reasoning should be viewed in relation to:

The Maitland Concept as a clinical practice framework for neuromusculoskeletal disorders

Setting the scene – the Maitland Concept as a clinical practice framework

The five pillars of clinical practice

Clinical reasoning

Professional and clinical competencies supporting physiotherapists as autonomous practitioners

The bio-psychosocial paradigm

Patient-centred practice

The patient and healthy living

Analyzing the patient experience

Patient inclusion and participation in decision making

Patient-centred communication

Understanding the body’s capacity to inform and adapt

The role of collaborative reasoning

Clinical reasoning

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine