CHAPTER 2 The history of Shiatsu

In a sense all the different forms of bodywork spring from a source as old as humanity itself, or even older. We humans, together with many other species of living creatures, have a long history of grooming, stroking and comforting each other through touch; massage is part of humankind’s worldwide heritage.

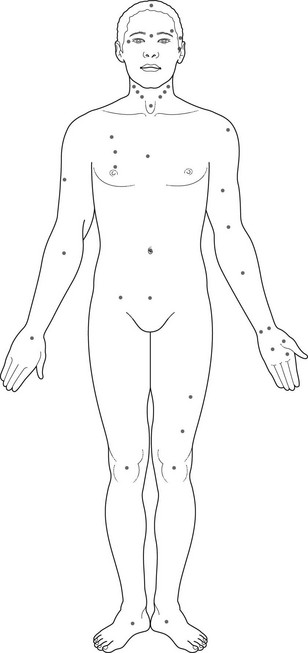

However, the technique of pressure along certain lines or to certain points is a practice belonging mainly to Asia. Southern India has its own system of channels (nadi) and points (varma or marma; Fig. 2.1) originally relating not so much to bodywork as to the martial arts and spiritual practice.

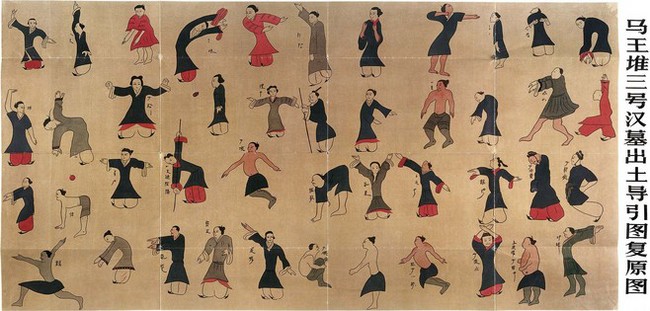

In the development of both Chinese and Japanese civilization from the time of Bodhidharma onwards, bodily as well as spiritual self-cultivation became as important for the physician as it was for the priest and the warrior. The practice of yangsheng (a combination of diet, sexual practices – known as fang zhong shu or the Art of the Bedchamber – together with inner alchemy, daoyin movement exercises and work with the breath, all in the interests of achieving long life or immortality) had a profound effect on the perception of the body. Particularly interesting are the manuscripts found in tombs of the Western Han (206 BCE–24 CE), which illustrate forms of exercise practiced at that time resembling modern-day Qi Gong (Fig. 2.2). These tombs were excavated in the 1970s and the discovery of their contents may well have influenced the later development of Shiatsu.

During this period, which saw the beginning of the great flowering of Chinese medical theory and the emergence of the system of meridians or channels which was to influence the medicine of the East to the present day, self-development techniques provided a window of insight into the experience of consciousness within the body.

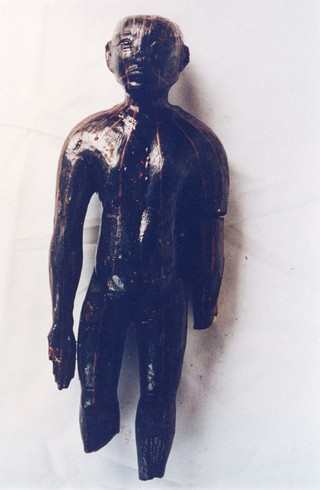

The inner experience of the yangsheng practices at this time led to the perception of Qi (see p. 394) and its flows within the body. In one of the recently excavated tombs was found an artefact now known as the Mianyang figurine (Fig. 2.3), buried no later than 118 BCE, which bears the first known representation of meridians or channels. Many of these lines resemble the classical meridians still known and studied today by acupuncturists, and others may have influenced one of the great innovators of Shiatsu theory, Shizuto Masunaga (Fig. 2.4) (see p. 150).

For nearly two centuries, therefore, the Japanese nation turned back in on itself, deprived of full contact with the rest of the world. In consequence, its culture acquired a characteristic attention to refinement and detail. One result of the isolation period was that palpation of the body remained an important part of the Japanese medical repertoire. Until the beginning of the 19th century in Japan all doctors were required to be qualified in Anma, the traditional Japanese massage similar to Chinese Tuina.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree