CHAPTER 11 Zen Shiatsu

In order for any form of energy medicine to make sense there has to be a concept of the way in which ‘energy’ becomes ‘form’, and the Chinese concept, one of the most convincingly developed and best recorded in the world of energy medicine, is simply summarized thus by Lao Tzu:

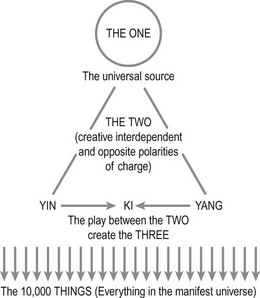

This refers to the One, the Tao, from which emerges the interdependent and eternally inter-creative principles of Yin and Yang, the Two. From the Two, Yin and Yang, comes the Third, Ki. From Yin, Yang and Ki come the Ten Thousand Things, the world of phenomena, the material world as we know it (Fig. 11.1).

Here Lao Tzu summarizes the East Asian philosophy of the relationship between the immaterial and the material originating from the One Source and explains the path of development from energy to form. According to this philosophy, the material physical world is created by an animating principle or energy which in turn is created by the interplay of opposing yet complementary polarities which emerge from the One, the matrix, the basic ground of being of the universe. In the same way that hundreds of descendants can be produced in a couple of generations from the partnership of one couple, so the hundreds of different objects, materials and textures that you can see if you look around you now are produced essentially from the relationship of opposing qualities of charge, a process which is discussed in Chapter 3.

Western thought, however, except in the rarefied domain of quantum physics, emphasizes the material and denies the immaterial. Its world is the world of the Ten Thousand Things in which everything has contracted into the solidly ‘real’; each object is individual and isolated from everything else. And this perspective is widely upheld as self-evidently correct all over the planet.

Kyo and Jitsu

‘Full’ and ‘empty’ are not the only manifestations of Kyo and Jitsu, however – the Japanese words carry a host of other meanings* and we can explore the interrelationship of these two principles on several different levels.

Kyo and Jitsu as ‘empty’ and ‘full’ – the physical level

This physical manifestation of Yin and Yang as empty and full qualities within the body tissue can be very useful by itself as a way of dealing with physical distortions in the body. In a case, for example, where the muscles on one side of the spine are tight and those on the other side weak, if we concentrate our work on the weak and empty side the tight side will relax. In local treatment of a problem, finding tsubos into which we can penetrate without resistance, finding and treating nooks and crannies empty of Ki, is an effective strategy in creating balance: as the empty areas fill up, the tense ones can let go of their effort. This brings us to another manifestation of Kyo and Jitsu.

Jitsu and Kyo as desire and inattention – the mind level

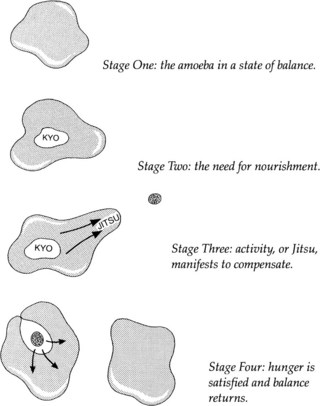

Now we have our first encounter with Masunaga’s amoeba. Figure 11.2 explains, via the amoeba, how Kyo and Jitsu act together in the process of cause and effect in all levels of our being.

Kyo and Jitsu Theory in Diagnosis and Treatment

While Kyo is not always a need, it is always an aspect of which we are currently unaware while our attention is upon the Jitsu. It can, for example, be a resource which we are not currently involved in using. If we diagnose Spleen Jitsu, Heart Kyo on a receiver, it may have the meaning that she is putting her energy into processing (Spleen) some kind of information, while no attention is going into the process of integrating (Heart) the information into her life.†

At any moment in the life of any being there will be processes which engage its attention and energy (Jitsu) whether consciously or unconsciously and others which do not (Kyo). The alternation and change of Kyo and Jitsu is part of the rhythm of life and not a condition of imbalance or disease. However, it can become so in certain circumstances, often as a result of automatic responses or conditioned behavior. Circumstances in the receiver’s early cultural or social environment may tend to lead to habitual patterns of Kyo and Jitsu or, alternatively, patterns in which the Jitsu does not resolve the Kyo. It is these habitual or inappropriate patterns which tend to create imbalances in the free flow of Ki, and thus lead eventually to ill-health of some description.

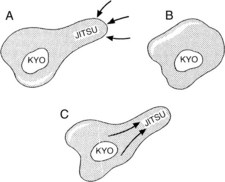

Although symptoms result both from the Jitsu and the Kyo, the Jitsu symptoms often have a Yang quality of urgency, because the receiver’s attention is drawn there. Many traditional Shiatsu styles are designed to deal with these obvious Jitsu symptoms, often by fairly forceful means. In terms of the sequence described above, this would be like finding the amoeba in Stage Three, with its obvious bulge, and trying to recreate the balanced state of Stage One by pressing the bulge back into place (Fig. 11.3A). This treatment, however, would only take the amoeba back to Stage Two, with the Kyo still hidden inside (Fig. 11.3B), and after a very short time it would tend to recreate the same Jitsu in response to its unrecognized Kyo (Fig. 11.3C). The same thing happens in humans if the Shiatsu treatment concentrates on the Jitsu symptoms and ignores the Kyo: the Jitsu comes back in the same symptoms or manifests as another set of symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree