The Acromioclavicular Joint

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint often gets overshadowed by the more glorious glenohumeral articulation. While its complexity and function are less intricate than those of the glenohumeral joint, pathology of this small joint can be extremely symptomatic. Pathology of the AC joint can be the result of acute trauma or more commonly can be due to overuse or intrinsic degeneration of the joint. Traumatic AC joint problems include AC joint separations (partial or complete), distal clavicle fractures, and rarely acromial fractures. Chronic problems include AC joint arthropathy, distal clavicle osteolysis (DCO), and symptomatic os acromiale. AC joint pathology is often related to activities such as weightlifting, contact sports, repetitive overhead lifting at work, and multiple other causes.

CHRONIC PROBLEMS

AC joint arthropathy can be quite symptomatic. Consistent physical exam findings in these patients include tenderness to palpation of the AC joint and pain with cross body adduction of the arm. In general, we utilize three criteria when deciding to perform a distal clavicle resection. These include a positive finding of pain on cross body adduction exam, tenderness to palpation at the AC joint, and workers’ compensation cases. If two out of three of the above criteria are met, we proceed with an arthroscopic distal clavicle resection. The technical pearls of this procedure were thoroughly covered in A Cowboy’s Guide to Advanced Shoulder Arthroscopy, so they will not be reviewed at length here. However, some of the important considerations include the following:

Figure 18.1 Right shoulder, posterior viewing portal, demonstrates spinal needle localization of the anterior portal that enters the glenohumeral joint over the lateral aspect of the subscapularis tendon. In addition to the intra-articular angle of approach, this placement usually provides a good angle of approach for distal clavicle excision. BT, biceps tendon; H, humerus; SSc, subscapularis tendon.

DISTAL CLAVICLE OSTEOLYSIS

DCO is a condition often found in younger patients who put high stresses on the AC joint, such as weightlifters, wrestlers, and football players. The etiology is not entirely understood but is presumed to involve disruption in the blood supply to the distal clavicle. With conservative treatment, symptoms often resolve with time and activity modifications. However, in cases of persistent symptoms, an arthroscopic distal clavicle excision can reliably alleviate symptoms.

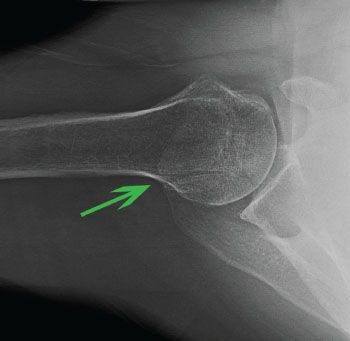

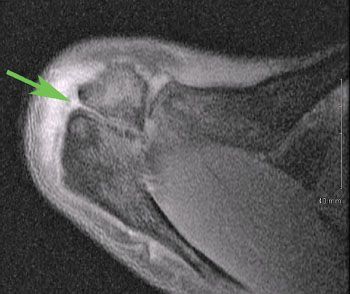

SYMPTOMATIC OS ACROMIALE

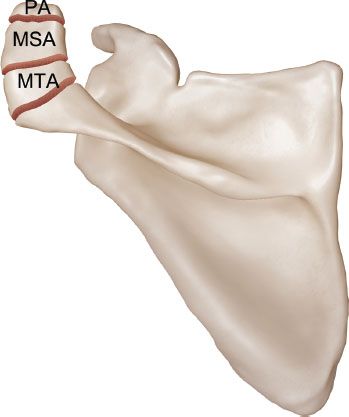

An os acromiale can be classified into three types—preacromion, mesoacromion, and metaacromion (Fig. 18.7). The mesoacromion variant is most common. The cleft in a mesoacromion usually lines up with the posterior border of the clavicle as viewed on an axillary radiograph or magnetic resonance image (MRI) (Figs. 18.8 and 18.9). Os acromiale pain can be confused with AC joint symptoms. It is important to recognize the presence or absence of an os acromiale when addressing anterior or superior shoulder pain. Recognition of this pathology will avoid mistakenly diagnosing AC joint pain and inappropriately performing a distal clavicle resection. This is particularly relevant because excision of a mesoacromion after a previous distal clavicle excision can result in a relatively large bone defect in the anterior shoulder and may compromise deltoid function or predispose toward deltoid detachment.

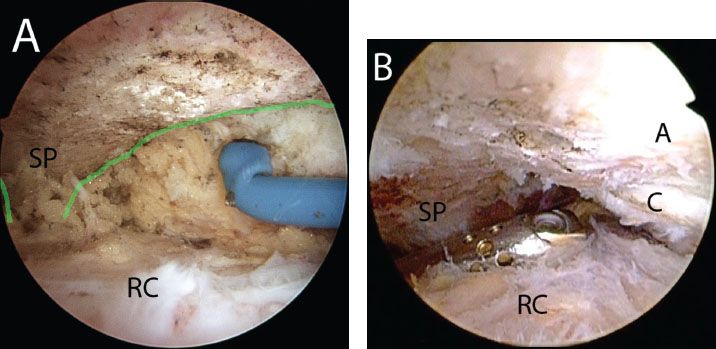

Figure 18.2 A: Right shoulder, lateral subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates skeletonization of the scapular spine (outlined by green line) in preparation for a distal clavicle resection. B: Clearing the soft tissue between the scapular spine and the AC joint provides a space for the arthroscope to view the AC joint from a posterior subacromial portal. A, acromion; C, distal clavicle; RC, rotator cuff; SP, scapular spine.

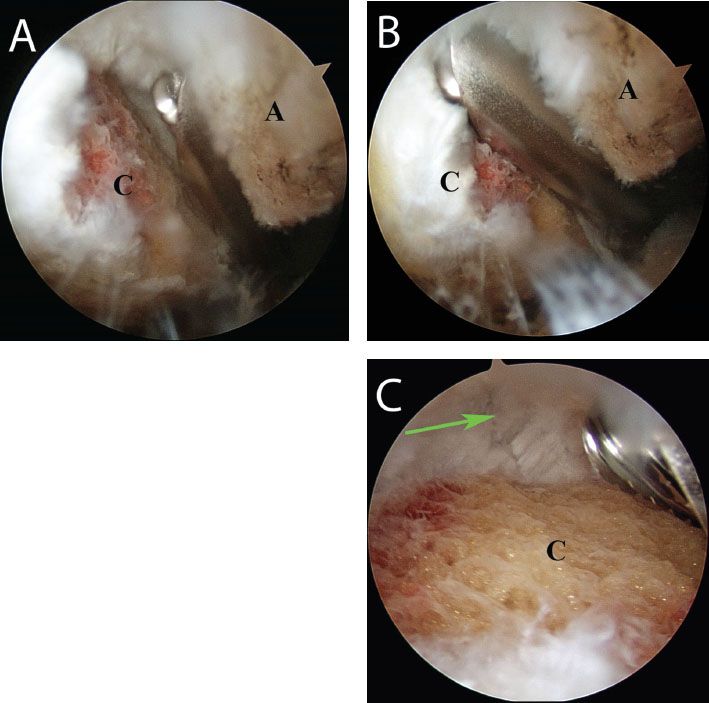

Figure 18.3 Right shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal. Resection of the distal clavicle proceeds from (A) anterior to (B) posterior, resecting approximately 1 cm of the distal clavicle. C: Care is taken to preserve the superior AC ligaments (green arrow). A, acromion; C, distal clavicle.

Typically, when we treat a patient with both a symptomatic mesoacromion and AC joint arthritis, we excise only the os acromiale segment. In fact, excision of the os acromiale fragment also addresses the AC joint arthropathy since the distal clavicle will no longer have any bone to articulate against. When an os acromiale occurs in association with a rotator cuff tear, we perform an acromioplasty, just as if there were not an os acromiale, so as not to compromise the coracoacromial arch. The complication rate from attempted fusion of an os acromiale is so high that we never attempt to fuse an os acromiale.

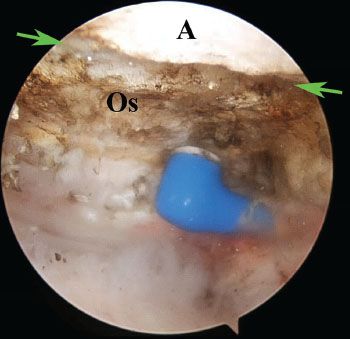

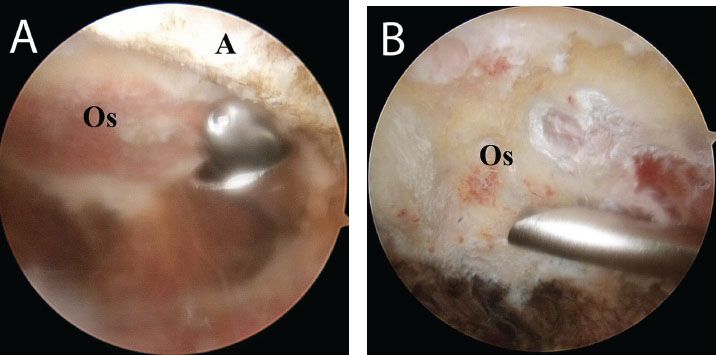

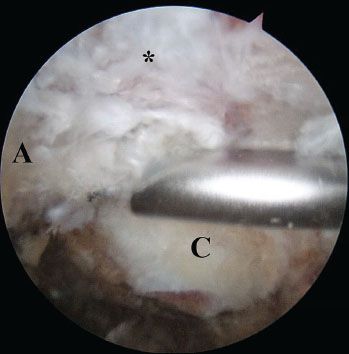

Os Acromiale Excision

The subacromial space is cleared through a lateral portal while viewing with a 30° arthroscope from a posterior portal. Electrocautery is used to skeletonize the undersurface of the acromion and expose the synchrondosis of the os acromiale segment (Fig. 18.10). The mesoacromion is then excised with a burr beginning laterally and working medially (Fig. 18.11). Care is taken to preserve the periosteal layer between the superior acromion and the deltoid muscle (Fig. 18.12). The excision is continued until all visible os acromiale bone is removed. The arthroscope is moved to the lateral portal to confirm a complete excision (Fig. 18.13). Any residual os acromiale can be excised using a burr introduced from an anterior portal (Fig. 18.14).

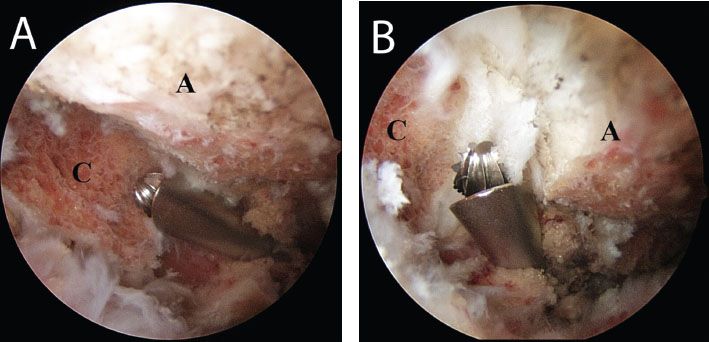

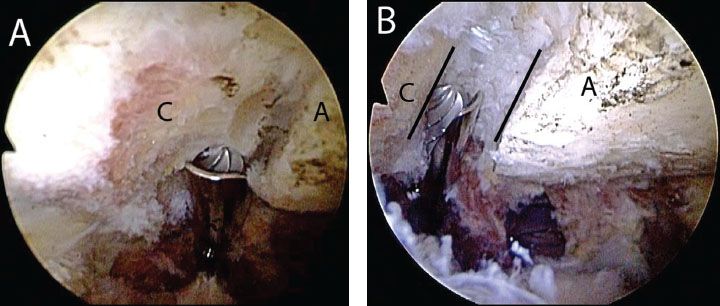

Figure 18.4 Right shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates comparative field of view of the AC joint obtained with (A) a 30° arthroscope and (B) a 70° arthroscope. A, acromion; C, distal clavicle.

Figure 18.5 A: Right shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal with a 30° arthroscope. In this case, there is a reverse obliquity to the AC joint that prevents visualization of the superior aspect of the joint with a 30° arthroscope from a posterior subacromial portal. A 70° arthroscope is required to perform the resection from this portal. B: View with a 70° arthroscope postresection of the distal clavicle. Note: The obliquity of the AC joint (black lines) and that the superior aspect of the joint is clearly visualized. A, acromion; C, distal clavicle.

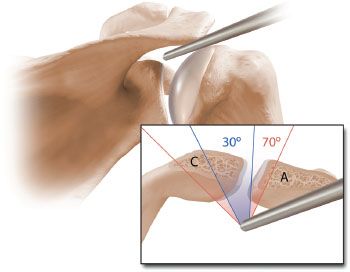

Figure 18.6 Schematic illustration of the view of the AC joint from a posterior portal. A 30° arthroscope provides a limited field of view (shaded in blue). The field of view with this arthroscope may not be sufficient to visualize the superior aspect of the joint, particularly when there is an oblique orientation of the joint. The 70° arthroscope provides a larger field of view (shaded in red) and with this arthroscope the superior aspect of the joint can always be visualized. A, acromion; C, distal clavicle.

Figure 18.7 Schematic of the different types of os acromiale. MSA, mesoacromion; MTA, metaacromion; PA, preacromion.

ACUTE AC JOINT INJURIES

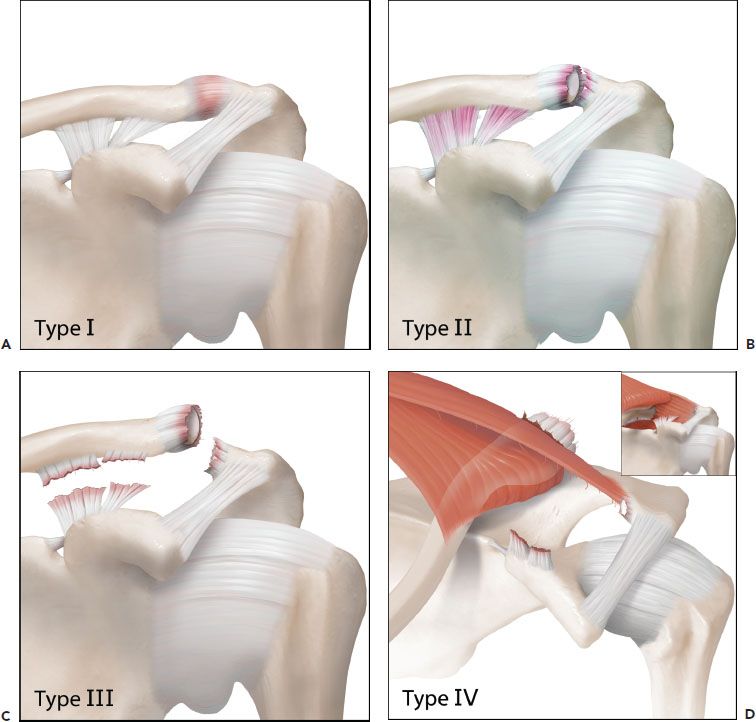

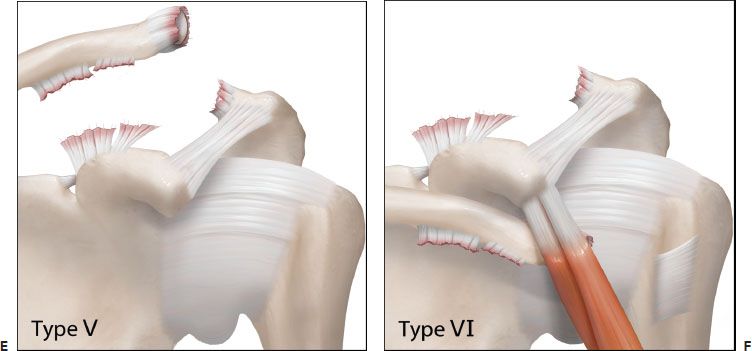

AC joint separations are common injuries and have been divided into six subtypes (Fig. 18.15). Conservative treatment is appropriate for grade I and II separations as these injuries typically improve with time and modification of activities. Conversely, grade IV through VI separations respond poorly to conservative care and are thus usually managed operatively. The major area of controversy surrounding AC separations is the management of grade III injuries. Historically, several studies suggested that nonoperative management of grade III injuries is equivalent or superior to operative management (1,2). However, there are several limitations to these studies. In these older studies, the patient population was likely less active with lower athletic demands compared to current patients. Additionally, several of these studies were published prior to the creation or routine use of validated patient-directed outcome measures. Third, the fixation methods employed during these older operative repairs have been shown to be woefully inadequate from a biomechanical standpoint. Finally, the technique for repair of an AC joint separation has evolved from historical open methods to the current age where a less invasive arthroscopic technique is reproducible.

Figure 18.10 Right shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal demonstrates use of an electrocautery to skeletonize an os acromiale (borders marked by green arrows). A, acromion; Os, os acromiale.

Due to the above factors, we now commonly offer operative management to many active patients with grade III AC separations. While operative management is not indicated for every patient, we believe that a significant proportion of patients will benefit from reconstruction. Specifically, patients with physically demanding occupation or athletes who participate in overhead sports, or patients with hobbies that require significant use of the shoulder, may benefit appreciably from AC joint reconstruction after a grade III separation.

Figure 18.11 A,B: Right shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates resection of an os acromiale with a burr working from lateral to medial and posterior to anterior. A, acromion; Os, os acromiale.

Figure 18.12 Right shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal. During resection of an os acromiale, care is taken to preserve the origin of the deltoid on the acromion (asterisk).

Figure 18.13 Right shoulder, lateral subacromial viewing portal. After preliminary resection of an os acromiale from a posterior portal, the arthroscope is moved to a lateral portal to confirm of a complete os acromiale excision. Note: The deltoid origin on the acromion (asterisk) has been preserved. A, acromion; C, distal clavicle.

Figure 18.14 Right shoulder, lateral subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates fine-tuning of an os acromiale excision with a burr introduced from an anterior portal. A, acromion; C, distal clavicle; asterisk, deltoid origin.

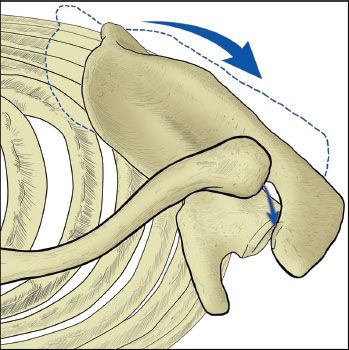

There are several consequences to a misaligned AC joint. Cosmesis is often a concern to patients but should not be a strong indication for surgical intervention except in the most unusual of circumstances. We remind each patient that surgery for cosmesis alone just trades a lump for a scar. More important to consider is the potential functional compromise. Overhead athletes may have chronic issues of pain to varying degrees. Similar to a shortened midshaft clavicle fracture, an AC joint separation can lead to scapular protraction that has biomechanical ramifications on the shoulder. Commonly, this will manifest as posterior trapezial and scapular pain as a result of this muscle being under constant tension in an abnormal anatomical position. High-demand patients also often report fatigue with repeated activities as well as shoulder impingement. Common physical examination findings include impingement signs, coracoid tenderness, and scapular dyskinesis as a result of scapular protraction (Fig. 18.16).

Another consideration in patients with acute AC joint separations is the degree of associated pathology in the shoulder. In two recent studies of patients with grade III separation and an average patient age of 38 and 35 years, the incidence of additional associated shoulder pathology was 14% to 18% (3,4). Also for patients in an older age group, the actual incidence may be even greater. In a review of pooled data from the BRASS group (Burkhart’s Research Association of Shoulder Specialists), over 100 patients undergoing AC joint reconstructions were reviewed and we noted approximately a 35% risk of associated pathology. In light of this information, patients with a grade III AC joint separation should receive a thorough exam and MRI should be considered early in their workup to rule out any associated pathology, particularly if a nonoperative treatment course is not proceeding as expected.

While multiple techniques for AC joint reconstruction have been described in the literature, the most widely utilized historically has been the Weaver-Dunn reconstruction. This procedure, however, is a nonanatomic reconstruction and also has significant biomechanical limitations. Cadaveric studies have shown that while intact coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments fail at 725 N of load, the transferred CA ligament (i.e., the Weaver-Dunn procedure) offers only 145 N until failure (5). Having performed many Weaver-Dunn procedures in the past, we can also clinically attest that there is a high variability in the quality of the coracoacromial ligament. Sometimes, it is stout and offers excellent tissue to repair, while at other times it is thin and inadequate for AC joint reconstruction. This inconsistency likely contributes to the poor outcomes with the Weaver-Dunn reconstruction (6).

Figure 18.15 Schematic of the six types of AC joint separations. A: A grade I injury involves a strain of the AC ligaments only. B: A grade II injury includes disruption of the AC ligaments, but the CC ligaments are intact. C: In a grade III injury, the AC and CC ligaments are disrupted, but the deltoid fascia remains intact and displacement of the coracoid relative to the clavicle is <100%. D: In a grade IV injury, the AC and CC ligaments are disrupted and the clavicle is displaced posteriorly into or through (inset) the trapezius muscle. E: In a grade V injury, the AC and CC ligaments are disrupted and the CC displacement is >100% relative to the contralateral distance. F: In a grade VI injury, the clavicle is displaced inferior to the coracoid.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree