Tenodesis for Treatment of Scapholunate Instability

Marc García-Elías

Angel Ferreres

DEFINITION

Scapholunate dissociation (SLD) is a symptomatic wrist dysfunction that results from partial or total rupture of the scapholunate ligamentous complex, with or without carpal malalignment.6,7

It may appear either as an isolated injury or associated with other local injuries, such as distal radius fractures or displaced scaphoid fractures.

Usually the result of trauma (hyperextension and ulnar deviation injury to the wrist); SLD may also result from a chronic inflammatory arthropathy (rheumatoid arthritis, chondrocalcinosis).

ANATOMY

Under load the scaphoid is inherently unstable owing to its oblique alignment relative to the direction of axial forces being transmitted across the wrist.10 Under load the scaphoid tends to collapse into flexion and pronation. The magnitude of such rotation depends on the following factors:

The geometry of the radioscaphoid joint (the deeper the scaphoid fossa, the less unstable tends to be the scaphoid)

The stabilizing efficacy of the periscaphoid ligaments (proximal scapholunate interosseous ligament complex, dorsal scaphotriquetral [STq], palmar radioscaphocapitate [RSC], palmar scaphocapitate [SC], and lateral scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal [STT] ligaments)10

The dynamic action of muscles crossing the wrist.8 The extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) has a dorsal position at the level of the ulnar head while inserting at the anteromedial corner of the fifth metacarpal. Because of this obliqueness, when it contracts isometrically, it provokes pronation to the distal row relative to the radius. Other tendons (flexor carpi radialis [FCR], extensor carpi radialis longus [ECRL], abductor pollicis longus [APL]) have opposite obliqueness inducing supination. Intracarpal pronation tends to destabilize the scaphoid by pulling it away from the lunate. Therefore, the more effective the supinators, the more stable the scaphoid will be.

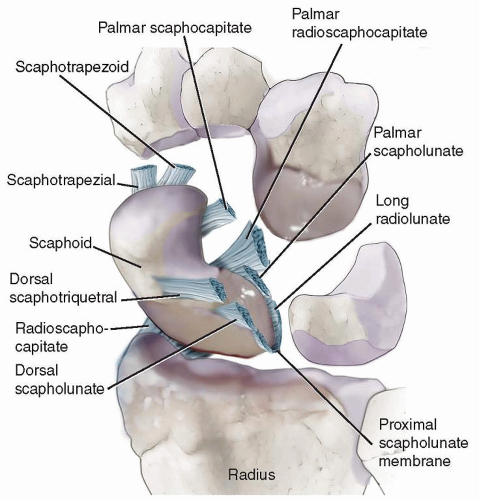

The scapholunate interosseous ligament complex consists of three structures: the two scapholunate ligaments (palmar and dorsal) and the proximal fibrocartilaginous membrane.

The proximal membrane connects the two adjacent convex borders of the two bones from dorsal to palmar, separating the radiocarpal and midcarpal joint spaces (FIG 1).

The dorsal scapholunate ligament is formed by dense, slightly oblique connective fibers that link the dorsal aspects of the scaphoid and lunate bones.

The palmar scapholunate ligament has longer and more obliquely oriented fibers, allowing substantial rotation of the scaphoid relative to the lunate.

The dorsal scapholunate ligament has the greatest yield strength (260 Newtons [N] on average), followed by the palmar scapholunate ligament (118 N) and the proximal membrane (63 N).2

The proximal portion of the membrane often appears perforated in middle-aged and older individuals, which does not cause instability.

PATHOGENESIS

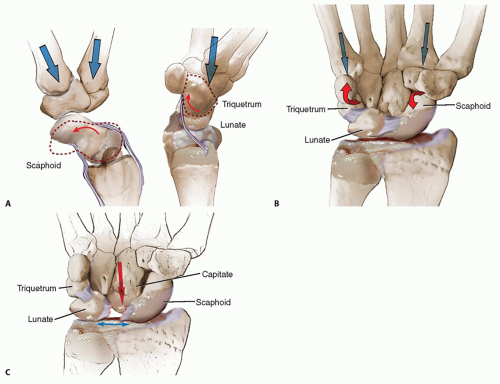

When axially loaded, the three proximal bones do not react equally in terms of direction of rotation. The scaphoid tends to rotate into flexion and pronation while the triquetrum is pulled into extension by the dorsally subluxing hamate bone (FIG 2A). If both the palmar and dorsal scapholunate and lunotriquetral (LTq) ligaments are intact, such differences in reactive motion generate increasing torques at both scapholunate and LTq levels, resulting in an increasing coaptation of these joints. Such an increased coaptation further contributes to the proximal carpal row stability (FIG 2B).

If the scapholunate ligaments are completely torn, the scaphoid no longer appears constrained by the rest of the

proximal row and tends to collapse into an abnormally flexed and pronated posture (“rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid”).

By contrast, the lunate and triquetrum rotate abnormally into extension, a pattern of carpal malalignment known as a dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) (FIG 2C).

If, in these circumstances, the short radiolunate ligament is also torn or insufficient, the lunate will follow its natural tendency of slide down the ulnarly inclined distal radial surface and will appear translocated ulnarly and palmarly.4

NATURAL HISTORY

Partial scapholunate ligament injury may not be radiologically demonstrable and may not produce symptoms unless the wrist is overloaded and/or there is poor muscle coordination in the stabilization of the carpal bones (predynamic instability).11

If left untreated, a partial scapholunate tear may progress toward a more complete disruption of the three portions of the scapholunate joint, in which case, a symptomatic dysfunction usually appears.

Radiographically, a gap between the scaphoid and lunate may be seen. This, however, is visible only under certain loading conditions (dynamic instability).

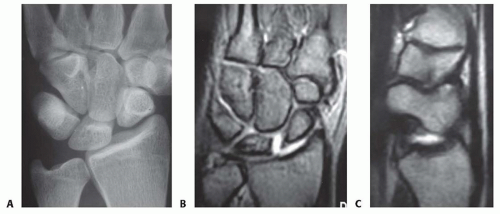

With time, the secondary stabilizers (STT and SC ligaments) may stretch out and become inefficient. In such circumstances, the scaphoid may collapse into flexion and pronation, whereas the rest of the wrist may progress toward permanent malalignment (static instability) (FIG 3A,B).

The wrist moves abnormally, with the lunate decreasing its range while progressively adopting an extended ulnar translocated position (DISI).

Conversely, the scaphoid collapses into flexion and pronation, with its proximal pole subluxing dorsoradially over the edge of the radioscaphoid fossa (FIG 3C).

The abnormal joint contact between radius and scaphoid may cause cartilage deterioration of the proximal pole of the scaphoid and the reactive formation of osteophytes at the dorsal edge of the radial styloid. This condition is known as scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC) stage 1.

If untreated, SLAC stage 1 may progress toward a more extended cartilage loss involving the entire scaphoid fossa (SLAC stage 2).

As the lunate becomes fixed in DISI, the dorsally subluxing capitate may present with cartilage deterioration progressing from radial to ulnar until it involves the entire capitolunate joint (SLAC stage 3).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Two clinical situations lead to a diagnosis of SLD. One is the patient who presents following violent trauma, such as a fall from a height or a motorcycle accident, who is likely

to have a major carpal derangement. Another is the patient who may not recall specific trauma and yet presents with symptoms.

In the first case, the diagnosis of a major SLD may be obvious.

In the second case, identification of the true nature of dysfunction may require a high index of suspicion, careful examination, and appropriate diagnostic tools.

Not uncommonly, arthroscopy is the only way to fully assess the extent of ligament derangement (see Chap. 68).

In both dynamic and static SLD, swelling may be moderate. In acute cases, range of motion may be limited by pain, whereas it may be normal in chronic cases.

Scapholunate point tenderness: If sharp pain is elicited by pressing the scapholunate area—a relatively soft spot located distal to the Lister tubercle—the probability of localized synovitis is high. Not all synovitis represents an injury to the scapholunate joint, however. Occult ganglia may present with a similar type of pain on palpation.

The resisted finger extension test11 has low specificity but excellent sensitivity. In the presence of scapholunate injury, sharp pain is elicited at the scapholunate area, representing dorsal subluxation of the scaphoid.

Scaphoid shift test11: If the scapholunate ligaments are completely torn, the proximal pole may sublux dorsally out of the radius in radial deviation, inducing pain on the dorsoradial aspect of the wrist. This test has low specificity: Occult ganglia, hyperlaxity, or radioscaphoid degenerative arthritis may produce similar symptoms.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Posteroanterior radiographic view of the neutral positioned wrist

Increased scapholunate joint space compared with the contralateral side (Terry Thomas sign) suggests static SLD.

A foreshortened appearance of the scaphoid with the scaphoid tuberosity projected in the form of a ring over the distal two-thirds of the scaphoid (ring sign) indicates rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid. The ring sign is not specific for SLD; it may also be present in static LTq dissociations and palmar midcarpal instability.

Lateral radiographic view

Increased scapholunate angle compared with the contralateral side. For this to be significant, the wrist needs to be in strict neutral alignment and neutral pronosupination and the angle needs to be greater than 80 degrees.

Examination of the moving wrist with an image intensifier is always advised. Sometimes, the scapholunate gap only appears in one particular position and/or loading condition; replicating that particular circumstance while scoping the wrist may ensure that the suspected dissociation is, indeed, present.

Arthroscopy is the gold standard technique in the diagnosis of SLD. It is also useful in describing the degree of injury to the interosseous ligaments.6

Magnetic resonance imaging may provide useful information regarding ligament integrity, bone vascularity, presence of local synovitis, and other soft tissue status.

Staging

SLD stage 1: partial scapholunate ligament injury, normal wrist alignment, usually diagnosed by arthroscopy, no abnormal scapholunate gap (Table 1)5

SLD stage 2: complete scapholunate ligament injury, reparable; complete disruption of scapholunate ligaments, the dorsal one being still reparable, with good healing potential; normal wrist alignment

SLD stage 3: complete scapholunate ligament injury, nonreparable, with a normally aligned scaphoid; dorsal scapholunate ligament with poor healing capability; normal carpal alignment

SLD stage 4: complete scapholunate ligament injury, nonreparable, reducible rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid; complete SLD plus detachment of the dorsal STq ligament off the distal margin of the lunate, plus insufficiency of the distal scaphoid stabilizers (STT and SC ligaments); rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid; radioscaphoid angle greater than 45 degrees. The lunate does not appear ulnarly translated but only in slight DISI.

SLD stage 5: complete scapholunate and radiolunate ligament injury, nonreparable, reducible rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid plus ulnar translocation of the lunate. The lunate is in substantial DISI and the radiolunate contact surface is reduced.4

SLD stage 6: complete scapholunate and radiolunate ligament injury with irreducible malalignment but normal cartilage; fixed, irreducible long-lasting malalignment, without cartilage degeneration

Table 1 Staging of Scapholunate Dissociation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access