32

Tendon Transfers

Indications

Tendon transfer surgery involves the operative repositioning of a tendon of a working muscle to take over the function of an absent or nonfunctioning muscle.1 Tendon transfer surgery is, above all, an attempt to rebalance an imbalanced hand (Fig. 32-1).

Indications for tendon transfer surgery include imbalance in the hand caused by central neurologic deficits, such as seen in spinal cord injuries or cerebral palsy, or trauma to the upper extremity where nerves and tendons are lacerated or crushed and cannot be repaired.2 Prolonged nerve compression can also lead to irreversible damage of muscle. Other causes for muscle imbalance are disease processes, such as poliomyelitis, rheumatoid arthritis, or Charcot Marie Tooth syndrome (which affects the intrinsic muscles of the hand causing wasting of the muscle fibers), and congenital deformities, such as those occurring with brachial plexus palsy or thumb hypoplasia.2–5

Additional procedures might include a free muscle transfer6 where the entire muscle-tendon unit is transferred with intact nerve and blood supply preserved; neurotization, or nerve transfer,2 which involves the implantation of a donor motor nerve into denervated vascularized muscle; or tenodesis,7 which is an automatic movement of a joint produced by a more proximal joint. A commonly cited example of tenodesis is demonstrated during active wrist extension when the digits and thumb fall naturally into flexion. Surgery can create or enhance a tenodesis effect by rerouting the transected tendon across a more proximal joint and attaching it there.

General Considerations

Alternative procedures may have been performed prior to tendon transfer surgery, such as nerve decompression, nerve repair, and muscle or tendon repair.1 Tendon transfers may be considered as a restorative option when there is no further recovery or nerve regeneration from the precipitating event. Surgeons typically wait 3 to 4 months for this plateau to occur.2–5

The prerequisites for this surgery are:1,2–5

• Edema or inflammation have subsided

• Expendable donor muscles (Muscles perform a certain function, but alternate muscles also perform the same function. The transfer of the expendable muscle does not in itself cause another deficit of motor function.)

Additionally, although it is implied, it should be stated openly that a key component for the success of this elective surgery lies in the motivation and understanding of the client. Without clearly-defined functional goals and a willingness to work toward the outcome, the surgical procedure by itself will not lead to improved outcomes. The client must demonstrate active participation in the process.8,9

The selection of the donor tendons must take into consideration the following:1,2–5,9

• A muscle that has sufficient strength to overcome the strength and passive tension of the antagonist muscle

• A muscle that lies in an appropriate direction of the desired action

• A muscle that travels a straight route and performs a single function

• Potential excursion of the muscle once it is freed from all connective tissue attachments

The muscle should contract through a distance about equal to the resting length of individual muscle fibers. The required excursion is the excursion needed to move a joint through its full range of motion (ROM), but the available excursion is limited by the surrounding connective tissue.1

Additional considerations that come into play are the staging of multiple procedures on both the flexor and the extensor sides of the extremity, and the selection of alternative procedures, such as arthrodesis (joint fusion) and/or tenodesis. The rehabilitation plan typically immobilizes and protects the transfer during the first 3 to 4 weeks post-surgery.1,2–4,8,9

Preoperative Treatment

Clients with peripheral nerve injuries can benefit from therapeutic intervention while awaiting either nerve regeneration or restorative surgery. The fabrication of well-designed orthoses can greatly increase the functional capabilities of clients diagnosed with radial, median, and/or ulnar nerve palsies. Left unsupported, these nerve injuries can lead to significant joint contractures and overstretching of muscle tendon units.8–12 At a minimum, peripheral nerve injuries cause joint stiffness and discomfort, as well as awkward posturing. A variety of immobilization or mobilization orthoses can be fabricated for this purpose:

• Clients with radial nerve palsy require support of the wrist and metacarpophalangeal (MP) joints in extension (Fig. 32-2).

• Clients with median nerve palsy require support and positioning of the thumb in opposition and abduction for fine motor tasks (Fig. 32-3 and Fig. 32-4).

• Clients with ulnar nerve palsy require that the MP joints be positioned in flexion to prevent clawing of the ulnar digits and to substitute for lack of intrinsic function. If the median nerve is also involved, clients may require additional support for the thumb in abduction (Fig. 32-5 and Fig. 32-6).

If the client has elected to proceed with tendon transfer surgery, therapeutic management includes the preoperative evaluation, conditioning, and client education.9,13 Unfortunately, many of the clients requiring hand therapy may not have been seen by you prior to their surgery. If this is the case with your client, you must work quickly and effectively to gain the client’s confidence and trust. But ideally, the entire process includes your contributions as the therapist, starting with the preoperative evaluation and coursing also through preoperative conditioning and education as well as postoperative rehabilitation. Working together for this extended time period reinforces the rapport between you and your client.

The Evaluation

• Assess the client’s ability to comply with the postoperative rehabilitative protocol. It is helpful if you have already worked with the client through their post trauma rehabilitation, but you can still develop a rapport with the client at any point by explaining concepts; developing a working relationship as coach, educator, and partner; and forming a treatment plan geared toward function.

• Record a detailed history of the injury, all of the surgical procedures, and all of the therapy that has taken place up to this point, leading to the decision for tendon transfer surgery.

• Examine the affected extremity; observe and record the skin appearance and the placement of scars, adhesions, atrophy of muscles, prominent bony landmarks, and skin coloring.

• Determine sensory status using the Semmes-Weinstein monofilament test, two-point discrimination testing, and/or stereognosis testing.9,14 When working with children, you will need to closely observe how they integrate the use of their involved hand into play. You can incorporate a game of stereognosis to determine their ability to interpret sensory input in their involved hand. Stereognosis refers to the ability to perceive and recognize the form of an object using cues from its size and texture. Evaluating a child may be a bit more challenging, but it is possible through creative and interactive play and by discussing your observations of the use of the affected extremity with the parents.9,13

• Take active range of motion (AROM) and passive range of motion (PROM) measurements. Evaluate each joint carefully to ascertain whether it has a hard or soft end feel, and note whether a contracture is present or if there is ligament laxity in the joint. If a contracture is present, you need to address this prior to surgery. If the joint is extremely lax, you should mention this to the surgeon so that the proper amount of tension can be applied during the surgery.

• Evaluate the current use of the hand through functional testing, such as the Jebsen Hand Function Test (JHFT), the functional dexterity test (FDT) (See Fig. 32-7), or the Moberg’s pickup test9,15.

In addition to the above assessments, observe the client’s movement patterns, and note all of the compensatory movement patterns.11,14 These are patterns of movement that your client may have begun to use to make up for the lack of normally functioning muscles. These movement patterns can lead to overstretching and weakening of muscles that are not yet injured. You will need to retrain your client not to use these patterns of movement after surgery. It is best to point these patterns out early and teach your client to recognize them. Instruct your client to avoid these movement patterns in preparation for the surgery.

Include one of the following client self-report outcome measures: the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) or QuickDASH, or the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ).13–17 These self-assessments contribute crucial information to an overall picture of how the client rates their own independent functioning, and theyhelp determine how your client views progress toward achievement of functional goals throughout the rehabilitation process.

Perform manual muscle testing (Table 32-1) to determine what muscles are indeed paralyzed and what muscles may act as donor muscles. It is important to ensure that all possible donor muscles are strong enough to be transferred to new positions.2,4,13,18 Donor muscles should function at a grade of full ROM against gravity or higher.1,9 Selecting the muscles that are typically described as donor muscles in textbooks as being available without verifying that they are present and active is not enough. Not everyone may have a palmaris longus (PL) tendon available for transfer!3

TABLE 32-1

| Grade | Terminology | Description |

| 5 | Normal | Full ROM and full strength |

| 4 | Good | Full ROM against gravity with some resistance |

| 3 | Fair | Full ROM against gravity |

| 2 | Poor | Full ROM with gravity eliminated |

| 1 | Trace | Slight contraction without joint movement |

| 0 | None | No evidence of contraction |

During the course of your evaluation, you can utilize an orthosis to simulate the proposed function of the tendon transfer. This can help a client see right away if changing the position of a specific joint can indeed improve function. For example, prior to opponensplasty (tendon transfers to restore thumb opposition), fabricate a short opponens thumb orthosis and observe the client’s ability to hold and/or pinch while wearing this orthosis.9–12 You may note that your client displays an improved pinch or an increased ability to hold a tool. Or you might try fabricating a wrist orthosis for a client contemplating tendon transfers for wrist extension. The ability to keep the wrist in extension greatly improves grasp and release patterns of the digits. Wearing a wrist orthosis might enable your client to demonstrate improved hand functioning. In addition, wrist support helps prevent shortening of the wrist flexors.9–12

Donor muscle strengthening can be performed through progressive resistive exercises and/or through biofeedback and/or neuromuscular electrical stimulation9 (Fig. 32-9). An example of this would be strengthening of the pronator teres (PT) muscle prior to transferring this tendon to the insertion of extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) for wrist extension after radial nerve palsy.

Make sure to inform clients of the loss of sensory input along the distribution of the injured peripheral nerve and the potential for burns and/or skin breakdown. It may be very obvious to your client when they have no feeling in the fingertips due to a median nerve or ulnar nerve injury. However, even the radial nerve has a sensory terminal branch, the dorsal sensory branch of the radial nerve. This area of insensate skin can be injured when the client begins to use their hand in activities of daily living (ADLs). Note bandage over dorsal first web in Fig. 32-10 where client burned herself removing items from a hot oven.

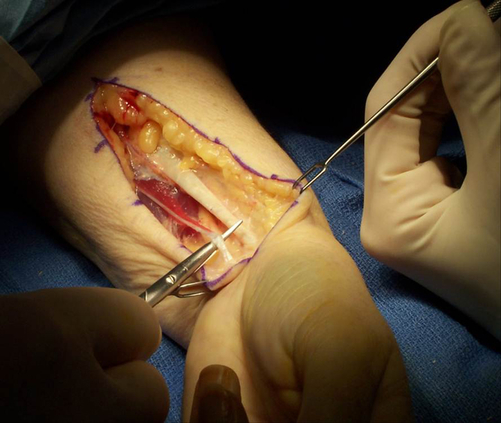

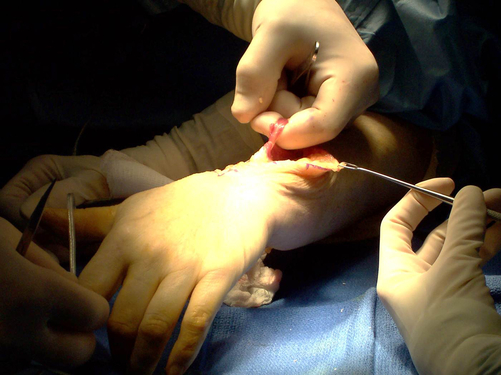

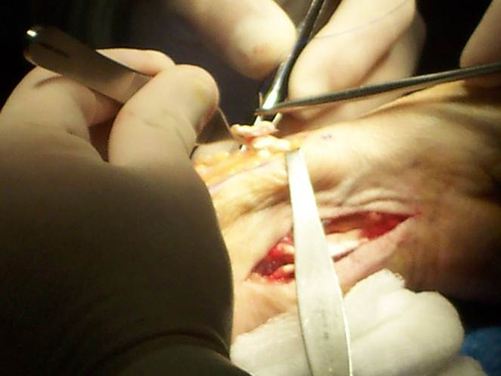

Operative Treatment: General Guidelines

Based on the requirements of each client and the results of the manual muscle testing, the surgeon selects the donor muscles for transfer. Various names have been assigned to specific sets of transferred tendons for each of the three main nerve palsies of the upper extremity. It is a good idea to be familiar with these classic procedural names, such as the Royle, Camitz, or Huber transfers for thumb abduction or opposition in median nerve palsy3,19–21 (Box 32-1); the Brand, Jones, and modified Boyes transfer for radial nerve palsy2–5,19 (Box 32-2); or the Brand, Stiles-Bunnel, or Zancolli Lasso procedures used in the treatment of ulnar nerve palsy8,18,21 (Box 32-3). There are many more names, procedures, and modifications described in the literature—nearly fifty for radial nerve palsy alone.3 Make sure you confer with the surgeon to specify exactly which donor muscles were utilized (Fig. 32-11 through Fig. 32-13).