Tendon Transfers Used for Treatment of Rheumatoid Disorders

Raymond J. Metz Jr.

Rey N. Ramirez

John D. Lubahn

DEFINITION

Rheumatoid arthritis is a progressive disease that, if uncontrolled, leads to joint destruction, secondary to progressive synovitis, ligament instability, joint dislocation or subluxation, and attrition of adjacent tendons either by bony erosion or direct tenosynovial infiltration.

When tendon rupture occurs on the dorsum of the hand or wrist, patients cannot extend their fingers and have difficulty grasping objects.

The most common tendon ruptures on the dorsum of the hand begin on the ulnar side and usually are a result of subluxation of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ), the so-called Vaughan-Jackson or caput ulnae syndrome.13

On the volar side of the wrist, the most common tendons to rupture are the flexor pollicis longus and the adjacent flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon to the index finger or possibly the long finger. This is referred to as Mannerfelt syndrome.9

ANATOMY

The extensor tendons of the hand and forearm pass beneath the extensor retinaculum at the wrist. The retinaculum is divided into six separate compartments lined by tenosynovium, which can become involved in the pathology of rheumatoid arthritis.

The first compartment contains the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis. The former tendon often contains multiple slips, which can contribute to limited space in its respective compartment and secondary de Quervain tenosynovitis.

The second compartment consists of the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), the former tendon inserting at the base of the index metacarpal and the latter at the base of the long finger.

The third compartment contains only the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL), which passes around the tubercle of Lister at a fairly sharp angle. Although frequently involved in tendon ruptures in rheumatoid arthritis, the EPL may also present as an isolated tendon rupture after nondisplaced fractures of the distal radius.

The fourth compartment contains the extensor indicis proprius (EIP) and the extensor digitorum communis (EDC), sending tendons from the common extensor muscle in the forearm to each of the fingers. The EIP is a separate muscle tendon unit located within the fourth compartment. It can be differentiated by its distal muscle belly.

The fifth extensor compartment contains the extensor digiti quinti (EDQ), often consisting of two slips and passing almost directly over the DRUJ.

The sixth compartment contains only the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU).

On the palmar side of the wrist, the flexor pollicis longus is located most radially and passes over the radiocarpal joint adjacent to the trapeziometacarpal joint of the thumb. The flexor pollicis, along with the median nerve and the profundus and sublimis tendons to each digit, passes beneath the deep transverse carpal ligament and represents the contents of the carpal canal.

Tenosynovial proliferation can exist within the carpal tunnel, arising from the undersurface of the ligament but more commonly proliferating along the tendons themselves.

PATHOGENESIS

Tendon rupture on the dorsum of the wrist is usually the result of instability in the DRUJ, leading to secondary subluxation and bony erosion through the capsule of the joint and then the tendon.

The tendon initially affected is the EDQ. As the carpus supinates and subluxates volarly, causing the distal ulna to be more dorsal, tendons typically rupture sequentially in an ulnar to radial direction.

The tendons may also be compromised by direct infiltration from the tenosynovium.

Although the ulnar tendons are involved most commonly, it is possible for all of the tendons crossing the dorsum of the wrist to rupture, making reconstruction more difficult.

On the volar side of the wrist, the flexor pollicis longus may become compromised through erosion by osteophytes and rough bony surfaces at the level of the trapeziometacarpal joint of the thumb or the scaphotrapezial articulation. The adjacent profundus tendon to the index and, occasionally, the long finger can rupture as well.

Tendons of the flexor surface of the wrist and forearm are also subject to rupture via direct tenosynovial infiltration, but this is less common.

In addition to tendon attrition and eventual rupture, tenosynovitis in the carpal tunnel may cause median nerve compression that leads to weakness of the median nerve innervated intrinsics. These include the opponens pollicis and abductor pollicis brevis (APB), the flexor pollicis brevis (usually only the deep head), and the radial two lumbricals. Weakness of these muscles is uncommon but should be checked in all patients with carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS).

NATURAL HISTORY

Before the advent of treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, the natural history was one of relentless progression. The disease would occasionally “burn itself out,” however, with the radiocarpal joint subluxating in a volar and radial direction, leading to instability and loss of function.

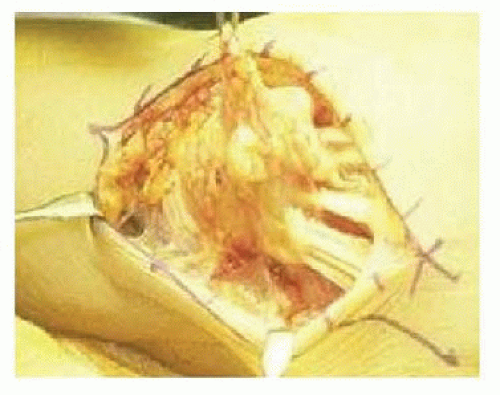

Also, before the development and routine use of antitumor necrosis factor drugs, patients were occasionally refractory to nonsteroidal medication, corticosteroids, and stronger anti-inflammatory drugs such as methotrexate. When these drug combinations failed, proliferative tenosynovitis occasionally occurred on the dorsum of the wrist, secondary to a “pannus” of diseased, thickened synovium growing directly into the tendons causing collagen destruction and rupture (FIG 1).

The worst-case scenario is secondary rupture of all of the finger extensors, with subluxation of the ECU volar to the axis of wrist motion such that it becomes more of a wrist flexor and ulnar deviator than a wrist extensor. The radial wrist extensors may also rupture; however, in part as a result of the more robust nature of the tendons themselves, they tend to remain intact even with progressive disease.

The French impressionist painter Pierre Auguste Renoir was said to have had such severe rheumatoid arthritis that in his later years, he would tape a brush to his hand to paint.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients often note a spontaneous loss of finger motion, but there may be minimal swelling and discomfort. Patients occasionally report a snap or twinge of discomfort as the tendon ruptures.

With an extensor tendon rupture, patients cannot actively extend the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints of the involved digit.

In the case of isolated rupture of the EDQ, an intact EDC to the small finger may make it difficult to confirm the diagnosis.

The proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of the finger may be extended through the intrinsics even when the extensors are ruptured.

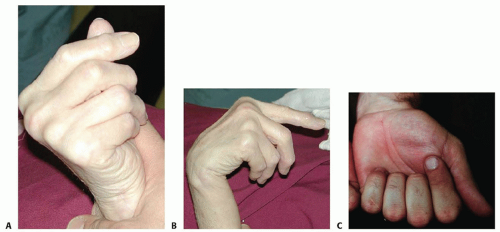

Wrist flexion should result in MCP joint extension through tenodesis if the extensor tendons are intact. When the finger extensors are ruptured, this tenodesis effect is absent (FIG 2A,B).

The patient should also be examined for subluxation of the extensor tendons, which may mimic tendon rupture. In this case, the tendon will subluxate ulnarly to lie between the MCP joints. Patients with subluxation rather than rupture should be able to maintain extended position if the MCP joints are passively extended.

On the volar side of the wrist, the examiner should check closely for the possibility of associated tenosynovial proliferation proximal and deep to the transverse carpal ligament.

Active digital motion may cause palpable crepitus at this level.

Such proliferation may result in coexisting CTS. The examiner should question the patient regarding symptoms of CTS and should assess for signs of CTS.

Examination findings suggestive of CTS include decreased sensation or paresthesias in the thumb, index, middle, and radial ring finger; thenar pain; Phalen compression test; and APB weakness.

The patient should also be examined carefully for active flexion at the distal interphalangeal joints of the index and long fingers as well as the interphalangeal joint of the thumb.

Absence of flexion should alert the surgeon to the possibility of rupture of the flexor pollicis longus and the FDP to the index and occasionally the long finger.

These tendons are particularly vulnerable when subluxation and spur formation are present at the trapeziometacarpal or scaphotrapezial joints as well as the volar radiocarpal joint.

Tendon rupture at this level is referred to as Mannerfelt syndrome (FIG 2C) and needs to be differentiated from anterior interosseous nerve palsy.

Direct pressure on the flexor pollicis longus muscle in the forearm should lead to passive flexion in the interphalangeal joint of the thumb if the tendon is intact.

The tenodesis test also is effective for the flexor pollicis longus and profundus and sublimis tendons to the fingers; however, in patients with progressive rheumatoid arthritis, the radiocarpal joint and the interphalangeal joints may become arthritic, making passive motion of the wrist and fingers somewhat more difficult and therefore the test more unreliable.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the hand and wrist should be obtained to look for subtle changes of the DRUJ, such as subluxation or a small osteophyte (FIG 3), which may be consistent with the physical findings of tendon rupture (FIG 4).

Similar attention should be paid to the volar surface of the radiocarpal joint and the trapeziometacarpal joint of the thumb as well as the scaphotrapezial and trapezoidal joints.

Radiographs should be examined for arthrosis and deformity, which may mimic tendon rupture by causing motion loss.

Radiographs of the cervical spine may reveal subluxation, possibly causing nerve compression and secondary sensory loss or weakness.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are not routinely needed.

FIG 3 • AP radiograph of the wrist of the patient in FIG 4 shows osteophyte formation in the DRUJ (arrow). (From Lubahn JD, Wolfe TL. Surgical treatment and rehabilitation and tendon ruptures in the rheumatoid hand. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, et al, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, ed 5. St. Louis: Mosby, 2002:1598-1607.)

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies may be helpful in the evaluation of the patient with potential tendon ruptures, particularly if tenodesis testing is normal in the face of a loss of active finger extension or flexion.

Compression of both the anterior interosseous and posterior interosseous nerves can occur in rheumatoid arthritis, usually secondary to ganglion cyst formation at the level of the elbow joint.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In the case of tendon ruptures on the dorsum of the hand and wrist, the differential diagnosis is primarily that of posterior interosseous nerve compression or posterior interosseous nerve syndrome.

Compression of the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve, or the radial nerve itself more proximally, needs to be considered as the cause of the patient’s inability to extend the fingers. Careful physical examination of the proximal forearm and elbow is therefore important to include a large cyst, lipoma, radiocapitellar effusion, or other elbow abnormality that may be causing compression of the radial nerve more proximally and leading to muscle paralysis. Electrophysiologic testing may also prove helpful.

With respect to Mannerfelt syndrome, absence of flexion at the interphalangeal joint of the thumb and the distal interphalangeal joints in the index and long fingers should be differentiated from the anterior interosseous nerve syndrome, which when present in rheumatoid arthritis is usually due to a large ganglion originating on the volar surface of the elbow.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management probably is more feasible with respect to Mannerfelt syndrome than with the Vaughn-Jackson or caput ulnae syndrome. Although the functional deficit is generally greater with loss of finger extensors than loss of active flexion of the interphalangeal joint of the thumb and distal interphalangeal joints of the index and long fingers, some patients may still function remarkably well.

Supportive measures in patients who for one reason or another are not deemed suitable surgical candidates may be provided by a certified hand therapist or occupational therapist able to assist the patient with his or her activities of daily living.

With median nerve entrapment and compression from the proliferative tenosynovitis at the level of the radiocarpal joint, disability becomes more progressive and nonsurgical treatment more difficult. There may be a role for corticosteroid injection at the level of the radiocarpal joint, and certainly, referral to a rheumatologist is crucial for the control and management of the disease before any surgical intervention.

In the case of wrist or finger extensor tendon rupture, nonsurgical treatment may be beneficial in terms of resting the radiocarpal joint and interphalangeal joints of the fingers to prevent further tendon rupture by attrition. Splinting the wrist or hand may prove beneficial for pain control and to prevent further damage to the joints and soft tissues.

Nonoperative management of thenar atrophy may be justified if there is an ulnar innervated deep muscle head of the flexor pollicis brevis to serve as a strong palmar flexor of the thumb. Lack of opposition may be of minimal functional significance, especially in the nondominant hand. If there is lack of sensation, the benefits of opposition transfer will be even smaller. Careful patient selection is critical.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Basic Principles of Tendon Transfer

A large variety of donor options exist. Considerations for donor selection include (1) expendability, (2) synergistic function between original and new function, (3) independent function, (4) good voluntary control, (5) straight line of pull or requirement of minimal (no more than one) pulleys, (6) avoidance of scarred or skin grafted areas, (7) sufficient muscle excursion, and (8) sufficient muscle power. Transferred muscles can be expected to lose one grade of strength.6

Use of a Pulvertaft weave rather than end-to-end repair will greatly decrease the risk of rupture.

Restore full range of motion prior to tendon transfer. Transfers will not be able to move stiff joints.

Avoid surgery in patients with open wounds or uncontrolled disease.

Insensate areas are less likely to benefit from transfer.

If diagnosed early, an interposition graft may be used to reconstruct the ruptured tendon.7 The palmaris tendon, a strip of the flexor carpi radialis (FCR), and a slip of the EDQ are suitable choices.

Outcomes are similar between tendon transfer and tendon reconstruction with graft. Results correlate inversely with number of fingers involved or chronicity of injury.5

Extensor Tendon Rupture

A variety of tendon transfers are available for reconstruction of single and multiple extensor tendon ruptures.

It is important for the surgeon to locate the site of tendon rupture and identify as well as treat the cause.

Usually, rupture is secondary to the distal ulna subluxating dorsally through the attenuated fibers of the DRUJ. When subluxation occurs at this level, it erodes through the floor of the fourth and fifth extensor compartments.

Tendon reconstruction is therefore not complete unless it involves removal of the dorsal osteophyte by a modified Darrach procedure and coverage of the distal ulna with a flap of extensor retinaculum.

When the distal ulna is unstable, the pronator quadratus may be brought dorsal to stabilize the bone. The ECU or flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) combined with ECU2 may also be considered.

Small finger extension loss

Single tendon rupture of the EDQ may go unnoticed, particularly if there is a strong EDC to the small finger. Often, however, EDC contribution to the small finger is hypoplastic or absent and all that is present is a junctura tendinae from the small finger to the adjacent ring finger. Isolated loss of function in the EDQ is manifest by weakness or lack of extension of the small finger.

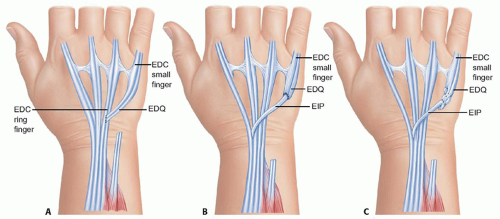

The distal stump of the ruptured tendon is sewn end to side to the intact ring finger EDC tendon. The risk of this transfer, however, is excessive abduction of the small finger when the distal tendon is short (FIG 5A). In general,

the transfer should be performed to the tendon of the adjacent EDC of the ring finger with the weave as far proximal as the distal stump of the EDQ will allow.

Alternatively, an EIP transfer may be performed (FIG 5B,C).

Ring and small fingers extension loss

In addition to the EDC tendons to the ring and small fingers, the EDQ usually will have ruptured.

The EIP is transferred to the EDQ.

The distal ring finger EDC tendon is transferred end to side to the adjacent intact long finger EDC tendon (FIG 6). Alternately, the distal stumps of the EDC ring and small and EDQ may each be woven to the EIP.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree