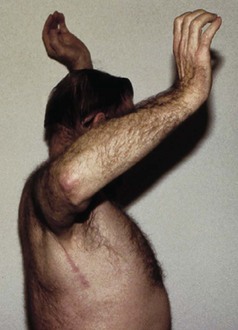

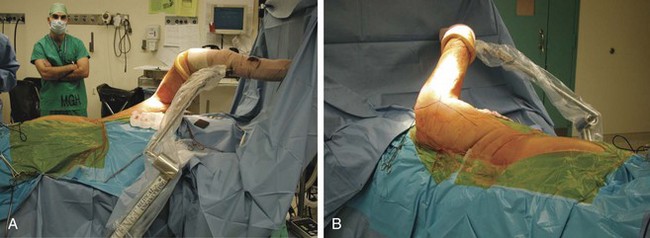

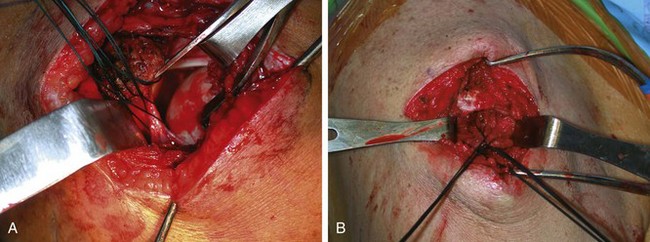

Chapter 25 Direct primary repair achieves reliable pain relief and functional improvement in the majority of rotator cuff tears.1–3 However, less commonly, very large musculotendinous defects, static superior subluxation of the humeral head, chronicity, and poor bone or tendon tissue quality may preclude successful primary repair.2,4–7 In such cases, alternative reconstructive surgical techniques should be considered. Historically, the management of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears had encompassed a wide range of surgical procedures, including open or arthroscopic debridement, muscle or tendon transposition (upper subscapularis, teres minor, teres major, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major, trapezius, deltoid, biceps, and triceps), tendon allografts, synthetic graft material, xenograft, and arthroplasty.8–15 Although debridement may allow pain relief in the low-demand patient,16,17 function is not reliably restored.2,18 Bridging of tendinous gaps with allografts and xenografts has not gained widespread acceptance because of variable functional results and inability to reestablish the length-tension relationship of the rotator cuff.19 If the coracoacromial arch is intact, hemiarthroplasty may offer some relief in the setting of rotator cuff arthropathy,20,21 but this treatment rarely addresses functional limitations.22 Recently, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty has offered a promising solution for pain relief and concomitant functional improvement in older patients with irreparable tears; however, long-term data on the longevity of these prostheses are not available in the United States. Furthermore, a reverse prosthesis alone will not restore an external rotation deficit, which can be a persistent source of disability. For younger, high-demand patients, local or regional muscle and tendon transfers are viable treatment options that provide a vascularized, functional replacement of the affected musculotendinous unit when other repair methods are likely to fail. When a musculotendinous unit has become torn and retracted from its insertion, the constituent muscle fibers undergo atrophy secondary to disuse. Concomitantly, fatty infiltration of the muscle interstitium results from macroarchitectural changes in the muscle fiber pennation angle.23 Once these changes have occurred, the muscle may not generate the strength and excursion necessary for normal function, even after successful primary repair.1,2,6,23,24 Even if excursion is sufficient to allow primary repair, fatty infiltration appears to be an irreversible event that may permanently compromise mechanical integrity of the musculotendinous unit. Several donor muscles about the shoulder girdle have been shown to possess a suitable vector of pull, with adequate strength and amplitude to act as a surrogate rotator cuff tendon.25–33,54 Empirically derived functional tendon transfers, of proven efficacy in foot and hand surgery, have been used to restore shoulder function after obstetric palsy in children.29,34 The analogous situation in the adult can result from brachial plexopathy and iatrogenic, inherited, or degenerative injury to the neuromusculotendinous unit of the rotator cuff. Advancement or transposition of local and regional muscles has been described to treat commonly occurring massive degenerative rotator cuff tears.6,11,13 The two patterns of massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears are posterior superior and anterior superior configurations. Posterior superior rotator cuff tears are the most common type and involve the supraspinatus and infraspinatus (and occasionally the teres minor) tendons. Anterior superior rotator cuff tears involve the supraspinatus and the subscapularis. In this chapter, we review two reliable regional tendon transfers for treatment of the most commonly occurring deficits in the rotator cuff: the irreparable, massive posterior superior rotator cuff tear and the irreparable subscapularis tear (Table 25-1). TABLE 25-1 Local and Regional Tendon Transfer Options for Muscle Deficits About the Shoulder • Atrophy of the spinati may be noted, indicating a chronic, massive tear. • Active forward flexion and external rotation are limited compared with the contralateral side. Motor testing of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus demonstrates weakness. • Passive motion should be well maintained in the tendon transfer candidate. • External rotation lag (a difference in passive and active external rotation arc) is indicative of a massive posterior cuff tear. An external rotation lag sign that persists in abduction, termed the signe du clarion (“hornblower’s sign”), indicates extension of the tear into the teres minor35 (Fig. 25-1). • Subscapularis function is intact (Gerber lift-off test). • It may be advantageous to perform an impingement test with a lidocaine injection into the subacromial space to test rotator cuff strength if the examination is limited by pain. • True anteroposterior (AP), scapular-Y, and axillary lateral views of the shoulder. • Plain films may demonstrate static superior subluxation of the humeral head. An acromiohumeral distance of less than 7 mm (normal, 10.5 mm) suggests an irreparable tear of the infraspinatus (Fig. 25-2A). • Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is performed to characterize the status of the rotator cuff tendons and to evaluate muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration.50 • A massive tear, defined as a tear encompassing two or more tendons, with grade 3 or 4 fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff musculature on MRI or computed tomography (CT) portends a poor prognosis for a successful primary repair and therefore is an indication for tendon transfer (Fig. 25-2B).7 Prior failed attempts at primary rotator cuff repair are not necessarily contraindications to a latissimus transfer, but more limited gains in satisfaction and function should be expected.36 Other relative contraindications include deltoid dysfunction, shoulder stiffness, severe rotator cuff tear arthropathy, and infection. If the beach chair position is selected, the patient is placed onto a custom beach chair device with retractable kidney rests, providing maximal exposure (T-Max Shoulder Positioner, Tenet Medical Engineering, Calgary, Canada). The beach chair position is relatively contraindicated in obese patients because of difficulty with surgical field exposure in the axilla. After induction, the patient is placed as far laterally on the table as possible to facilitate positioning of the surgeon during exposure. A first-generation cephalosporin is administered for prophylaxis. The operative limb and hemi-torso are prepared and draped in the usual sterile fashion and then secured by means of a sterile pneumatic arm holder (Spider Limb Positioner, Tenet Medical Engineering, Calgary, Canada). With this position the surgeon may easily approach the superior shoulder and the axilla without the need of an assistant to hold the extremity (Fig. 25-3). Alternatively, the lateral decubitus position may be used. After induction, the patient is placed into the lateral decubitus position on the far lateral side of a standard operating table. A full-length beanbag supports the patient’s body, with an axillary roll in place on the contralateral side. The Tenet arm holder is positioned at the midportion of the bed on the ventral side of the patient. Preparation and draping proceed in the standard fashion, with care taken to provide adequate exposure superiorly and posteriorly (Fig. 25-4). • Anterosuperior exposure: acromion, acromioclavicular joint, clavicle, and coracoid process. The incision is Langer’s lines over the lateral third of the acromion, beginning at the posterior edge of the acromion and extending anteriorly 1 cm lateral to the coracoid process. • Posteroinferior exposure: anterior border of the latissimus, triceps muscle belly, posterior deltoid. The posteroinferior incision of the latissimus dorsi is drawn parallel to the anterior border of the latissimus approximately 6 to 8 cm distal to the axillary fold. Proximally, the incision is curved superiorly parallel to the posterior axillary line to allow access to the posterior aspect of the deltoid (Fig. 25-5). Specific steps of this procedure are outlined in Box 25-1. 1: Superior Exposure, Cuff Assessment, and Mobilization We approach the rotator cuff first during the procedure to allow assessment of cuff tissue and placement of anchors before harvesting of the latissimus. A No. 10 scalpel is used to incise skin and subcutaneous tissue to the level of the deltoid fascia. Sharp dissection with the scalpel is used to develop skin flaps at this level adequate to allow visualization of the lateral acromion and interval between the anterior and middle deltoid. Electrocautery is used to secure hemostasis, and self-retaining retractors are placed. Next, the electrocautery is used to split the deltoid in line with its fibers for a distance of 4 to 5 cm between the anterior and middle heads of the deltoid. The anterior deltoid may be reflected subperiosteally off the acromion by means of the electrocautery to provide visualization of the rotator cuff, if necessary. The interval between the anterior deltoid and coracoacromial arch is identified, and the coracoacromial ligament attachment to the acromion is preserved. The subacromial bursa is excised. Placement of Army-Navy retractors or a self-retaining subacromial spreader may be useful for exposure of the rotator cuff. The torn edges of the rotator cuff are then tagged with No. 3 Ethibond, and a systematic release of the rotator cuff is performed. A No. 15 scalpel is employed to release the coracohumeral ligament, extra-articular subacromial adhesions, and the superior capsule of the glenohumeral joint just deep to the rotator cuff. Care is taken not to release more than 1.8 cm medial to the glenoid to avoid iatrogenic injury to the suprascapular nerve. If the biceps tendon is present, it is released from the supraglenoid tubercle and tenodesed in the biceps groove. Once releases have been performed, the compliance and excursion of the cuff are assessed for the possibility of primary repair (Fig. 25-6). 2: Greater Tuberosity Preparation (with Anchor Placement) If primary repair is deemed to be not feasible, the rotator cuff tendon edges are freshened with a scalpel and the greater tuberosity is prepared with a rongeur on its anterolateral surface. The footprint must be placed laterally enough to allow creation of an external rotation moment for the transferred tendon. Suture anchors are then placed to allow multiple fixation points and to reestablish the rotator cuff footprint, depending on the tear pattern. A moistened saline gauze is then packed into the wound, and attention is turned to the posteroinferior exposure (Fig. 25-7).

Tendon Transfers for Rotator Cuff Insufficiency

Deficit

Transfer Option

Infraspinatus (posteroinferior cuff)

Teres alone

Supraspinatus

Latissimus with or without teres major

Subscapularis (anterosuperior cuff)

Pectoralis major (split, clavicular head or sternal head)

Serratus anterior

Pectoralis major (split, sternal head)

Trapezius

Rhomboid, levator advancement (Eden-Lange procedure)

Latissimus Dorsi Transfer for Posterior Superior Rotator Cuff Tears

Physical Examination

Imaging

Contraindications

Surgical Technique

Surgical Landmarks and Incisions

Specific Steps

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree