Tendon Transfers for Median Nerve Palsy

Jeffrey B. Friedrich

Scott H. Kozin

DEFINITION

The median nerve can be compromised by any number of causes, including trauma, tumor, chronic compression, or synovitis.

Palsy of the median nerve can result in motor or sensory deficits, or both, within the distribution of this nerve.

ANATOMY

The median nerve enters the forearm between the two heads of the pronator teres muscle.

The median nerve travels down the forearm between the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) muscles to enter the carpal tunnel.

Along its course, the anterior interosseous nerve branches from the median nerve to provide innervation to the flexor pollicis longus, FDP to the index, and the pronator quadratus muscles.

The median nerve proper provides innervation to the flexor carpi radialis, pronator teres, FDS, palmaris longus (PL), and FDP to the long finger.

The palmar cutaneous branch arises from the median nerve 5 cm proximal to the wrist joint, crosses the wrist superficial to the transverse carpal ligament, and supplies sensibility to the thenar eminence.

Just proximal to the wrist, the median nerve becomes superficial and travels within the carpal tunnel.

The recurrent motor branch originates from the central or radial portion of the median nerve during its passage through the carpal tunnel. The recurrent branch usually passes distal to the transverse carpal ligament to innervate the thenar muscles. The nerve can also pass through the transverse carpal ligament (occurs in 5% to 7% of individuals).8

The thenar muscles are the opponens pollicis, flexor pollicis brevis, and abductor pollicis brevis. The flexor pollicis brevis muscle receives dual innervation from both the recurrent branch (superficial head) and the deep motor branch of the ulnar nerve (deep head).

The median nerve terminates into multiple sensory branches, which supply sensibility to the thumb, index, long, and ring (radial side) fingers. The sensory branches to the radial side of the index and radial side of the long fingers possess a minor motor component that sends a small branch that innervates the adjacent lumbrical muscle.

PATHOGENESIS

Most injuries to the median nerve occur at the wrist and affect the thenar muscles. The resultant functional loss is lack of thumb opposition.

Compression injuries are most common and are usually attributed to prolonged carpal tunnel syndrome.

Carpal tunnel compression may also be secondary to tumor, adjacent synovitis, or fracture-dislocation.

Penetrating or perforating injuries may directly damage the median nerve.

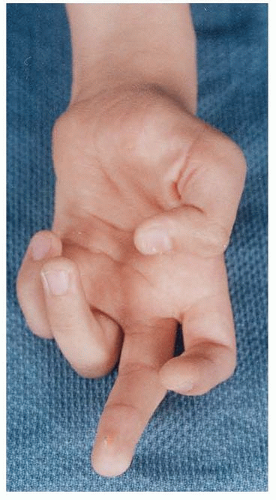

Pediatric causes include lipofibrohamartoma of the median nerve or Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, a demyelinating process that has a preference for the median and ulnar nerves (FIG 1).6,8

High median nerve injuries are rare. Similar causes exist, including trauma and nerve compression.11

NATURAL HISTORY

With a median nerve compression neuropathy (ie, carpal tunnel syndrome), palsy of the median nerve is insidious in onset and manifestation. Over a period of months to years, patients can progress to decreased median nerve function as well as sensory changes in the dermatome of this nerve.

Acute injuries to the median nerve at the wrist or elbow have a traumatic onset followed by abrupt sensory and/or motor changes depending on the extent of injury.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Compressive neuropathy of the median nerve

Patients report pain, numbness, and tingling in the thumb, index, middle, and sometimes ring finger of the affected hand. They frequently describe problems with fine coordination of the hand, notably pinch. Patients often report pain and numbness that awakens them at night.

Physical examination findings include thenar muscle wasting and diminished thumb opposition (defined as the combination of palmar abduction, metacarpophalangeal [MCP] joint flexion, and thumb pronation).

Additional signs include the Tinel sign; the Phalen sign; the carpal tunnel compression sign; and increased two-point discrimination in the thumb, index, and long fingers.

High median nerve neuropathies have similar findings, in addition to loss of forearm pronation and flexion of the thumb, index, and long fingers.

Acute median nerve injury

There is nearly always a wound on the upper extremity, usually on the volar wrist.

Physical findings include diminished sensibility in the thumb, index, and long fingers; increased two-point discrimination in those fingers; a positive Tinel sign; and an inability to touch the thumb tip to the small finger (ie, loss of opposition).

Depending on the level of injury, patients may display diminished sensibility of the thenar eminence of the thumb, indicating an injury proximal to the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve, or a concomitant injury to the palmar cutaneous branch.

Higher median nerve neuropathies have similar findings, in addition to loss of forearm pronation and flexion of the thumb, index, and long fingers.

Patients with median nerve palsy will not be able to oppose thumb to small finger. There may be some palmar abduction due to function of the abductor pollicis longus or extensor pollicis brevis muscles, but this will be minor. The ulnar-innervated deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis muscle will still function, yielding MCP joint flexion but not true opposition.

Inability to make an “OK” sign indicates anterior interosseous nerve injury and high median nerve pathology.11

The clinician should ask the patient to try to touch thumb to small finger with the wrist flexed. Due to median nerve palsy, the patient will likely be unable to fully touch the thumb to the small finger.

The patient is asked to spread his or her fingers apart and hold them against adduction pressure on the small finger to ensure ulnar nerve function. The examiner feels for resistance and palpates the hypothenar eminence at the same time. There should be resistance to adduction force on the small finger, and firmness of the hypothenar eminence should be appreciated.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographs

Plain radiographs are helpful in determining the nature of fractures or dislocations after acute trauma to the upper extremity.

Specific carpal tunnel radiographic views may demonstrate osteophytes within the carpal tunnel or a hook of the hamate, but they are not routinely performed.

Electrodiagnostic studies

In the setting of compressive neuropathy of the median nerve, nerve conduction studies typically show increased motor and sensory latencies in the median distribution.

In advanced stages of compressive neuropathy, electromyography demonstrates fibrillation potentials in various muscles tested, most commonly the abductor pollicis brevis. These fibrillation potentials indicate denervation of the tested muscle and axonal loss.

Advanced high median nerve neuropathy reveals fibrillation potentials in more proximal muscles, such as the flexor carpi radialis and the pronator teres.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Anterior interosseous syndrome

Pronator syndrome

Wrist synovitis

Direct injury to the median nerve

Tumor compression of the median nerve

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

Brachial plexus injury

Stroke or other brain injury

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Patients with demonstrable carpal tunnel syndrome can undergo a trial of splinting, wrist corticosteroid injection, or both.

Work modification is indicated in patients with compressive neuropathy as a result of overuse for both carpal tunnel and pronator syndromes.

Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory medications are indicated in patients with wrist synovitis secondary to inflammatory arthropathy.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The chief surgical modality for a low or high median nerve palsy that has not responded to surgery or other interventions is tendon transfer.1,3,8

Typically, in a low median nerve palsy, the only function that requires restoration via tendon transfer is thumb opposition, which is a combination of palmar abduction, MCP joint flexion, and thumb pronation.

In a high median nerve palsy, the additional loss of flexion of the thumb, index, and long fingers requires tendon transfer. In addition, lack of pronation may require tendon transfer.

Preoperative Planning

The surgeon must ensure that there is good passive range of motion of the joints to be motored by the tendon transfer.

In long-standing median nerve palsy, the thumb MCP and carpometacarpal joints can become quite stiff.

Physical therapy must be implemented to loosen these joints and increase their passive range of motion.3 This can usually be accomplished in 3 to 6 weeks.

A thorough assessment of muscle function and strength is made before selecting a transfer, especially in the setting of combined nerve deficits.

When performing an opponensplasty, the donor tendon and attachment site are individualized to the particular patient, his or her injury, his or her needs, and the donor muscle-tendon

availability. The vector of transfer is based about the pisiform to provide the most opposition regardless of the donor chosen. As the attachment site onto the thumb moves more dorsal, the amount of pronation and thumb extension is increased.

Donor options for opponensplasty include the following:

FDS8

Extensor indicis proprius (EIP)2

PL (Camitz). The palmaris transfer is associated with more abduction and less opposition compared to other opposition transfers secondary to its inability to transmit force from the pisiform.3,13

Opponensplasty attachment site options include the following3:

Abductor pollicis brevis tendon. This yields a great deal of thumb abduction and some opposition.

Extensor pollicis brevis or longus tendons. This yields thumb abduction, pronation, and MCP joint extension.

Single attachment options

Riordan’s technique involves interweaving the transferred tendon into the abductor pollicis brevis tendon, with continuation onto the extensor pollicis longus tendon distal to the MCP joint.

Littler’s technique attaches the transferred tendon into the abductor pollicis brevis tendon.

Bunnell’s method involves passing the tendon through a small drill hole made at the proximal phalanx base from the dorsoulnar to palmar radial direction to provide pronation of the thumb.

Dual attachment options

These are designed to rotate (pronate) the thumb and either passively stabilize the MCP joint or minimize interphalangeal joint flexion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree