Tendon Injuries Around the Foot and Ankle

Jonathan B. Feibel MD

Dane K. Wukich MD

Brian G. Donley MD

Tendon injuries around the foot and ankle are a common cause of disability in athletic individuals and a frequent reason for seeking orthopedic consultation. Some of these injuries are chronic, occurring over a period of time or with recurrent injuries, and others are acute, resulting from a single traumatic incident. Treatment requires a thorough understanding of the pathology surrounding each of these tendon injuries. Many can be treated with conservative methods, while others require operative intervention.

Achilles Tendon Disorders

Achilles tendon problems are common in those playing both competitive and recreational sports and can be caused by overuse that results in chronic tendon problems such as tendonitis or tendinosis or by trauma that results in acute or chronic Achilles tendon rupture. Factors that often contribute to Achilles tendon problems include training errors such as a sudden increase in activity, a sudden increase in training intensity (distance or frequency), resuming training after a long period of inactivity, running on uneven or loose terrain, postural problems (such as foot pronation), poor footwear (generally poor hindfoot support), or a tight gastroc-soleus complex.

Achilles Tendonitis

Introduction

Achilles tendonitis is a condition that develops over time and is associated with degeneration of the tendon and inflammation that causes pain. Achilles tendonitis is described as noninsertional or insertional, depending upon its location. The treatments of these two entities are very different.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of Achilles tendonitis is overuse. A hypovascular zone, 4 cm proximal to the tendon insertion on the calcaneus, is the most common location of noninsertional Achilles tendonitis. Microtears develop and lead to collagen degeneration, fibrosis, and calcifications within the tendon.1,2,4

Diagnosis

Patients often complain of pain posteriorly over the Achilles tendon. Fusiform swelling often is associated with the tendon degeneration. Activity-related pain is a common presenting complaint. Initially the pain is not debilitating, but as the degeneration continues, the pain becomes more severe.

With insertional Achilles tendonitis, the pain is directly over the posterior aspect of the calcaneus rather than over the Achilles tendon. More swelling is usually present, and often the calcaneus is prominent and inflamed.

A history and physical examination should rule out a stress fracture or an Achilles tendon rupture. Patients who have Achilles tendonitis have a reactive (normal) Thompson test. The Thompson test is done with the patient prone, with both feet extended off the end of the table. Both calf muscles are squeezed by the examiner. If the tendon is intact the foot will plantarflex when the calf is squeezed (reactive). If the tendon is ruptured, normal plantarflexion will not occur (nonreactive). Patients with an Achilles tendon rupture are unable to do a single heel rise. In patients with paratendinitis, tenderness remains in one position when the foot is moved from dorsiflexion to plantar flexion; in patients with tendinosis, the

“painful arc” sign is positive (the point of tenderness moves) because the thickened portion of the tendon moves with active plantarflexion and dorsiflexion of the ankle.

“painful arc” sign is positive (the point of tenderness moves) because the thickened portion of the tendon moves with active plantarflexion and dorsiflexion of the ankle.

Routine ankle radiographs should be taken to rule out other pathology or to show a spur associated with insertional Achilles tendonitis. Radiographs also can show calcification that often is present within the tendon. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also help to confirm the diagnosis of Achilles tendonitis and should be used if the history and physical examination do not clearly indicate the diagnosis. Ultrasonography has been reported to be effective in evaluating Achilles tendon pathology, but this technique is very dependent on a skilled ultrasonographer.

Treatment

The initial treatment of Achilles tendonitis should always be conservative. Initially, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug can be used in conjunction with a stretching program. Often a formal physical therapy program is helpful. An off-the-shelf heel lift that fits inside the shoe can take stress off the tendon. Corticosteroid injection rarely should be used in or around the tendon because of the reported association between corticosteroid injection and spontaneous Achilles tendon rupture.6 A recent retrospective cohort study, however, reported no ruptures in 43 patients at an average of 37 months after fluoroscopically guided, low-volume corticosteroid injections into the peritendinous space. If these modalities are unsuccessful, or the patient presents with severe pain, a removable walking boot or a short leg cast can be worn for 6 weeks to decrease inflammation. Because a walking boot can be removed for showering, patients generally are more willing to accept it than a cast.

If immobilization in the walking boot is successful, its use can be gradually decreased and the patient can resume activities. A posterior heel pad sock can be used to decrease friction on the calcaneal prominence.

A newer noninvasive treatment for Achilles tendonitis is extra corporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT). The same technology used to dissolve kidney stones has been reported to be effective for the treatment of a number of orthopedic disorders. It is done as an outpatient procedure with only a local block for anesthesia, and some sort of immobilization is needed for approximately 3 weeks to protect the tendon from rupture. The use of ESWT is currently not FDA approved for treatment of Achilles tendonitis, but some studies have reported its effectiveness. If conservative methods are unsuccessful in relieving symptoms, surgery is indicated.

Surgical Intervention

Noninsertional Tendonitis

Surgery for noninsertional Achilles tendonitis can be done percutaneously or through an open approach. Maffulli et al.7 reported better functional and cosmetic results and quicker return to activities after percutaneous longitudinal tenotomy than after open procedures.

Percutaneous Technique

The patient is placed prone on the operating table, and the area of maximal tenderness and swelling is marked. A no. 11 blade is placed longitudinal to the tendon fibers through the skin and the tendon. The blade is pointed proximally and is kept still as the ankle is moved into full dorsiflexion. The blade is then turned 180 degrees and the ankle is moved into plantarflexion. The procedure is repeated four times approximately 2 cm proximal (medial and lateral) and distal (medial and lateral) to the first incision. The wounds are closed with Steri-strips. An aggressive rehabilitation program is begun, with passive range of motion 2 or 3 days after surgery and a jogging program at 2 weeks.7

Maffulli et al.7 reported excellent subjective results in 25 of 48 middle- and long-distance runners, good results in 12, fair results in 7, and poor results in 4. Strength increased about 10% after the operation, and endurance improved almost 50%.

Open Technique

A posterior-based incision is made medial to the tendon at the area of maximal swelling or pain. Sharp dissection is carried to the paratenon. The paratenon is opened and the degenerative tendon segment is debrided with care taken to protect the integrity of the tendon and keep it in continuity. After debridement, the tendon is repaired using interrupted 0 nonabsorbable sutures, the paratenon is closed with 0 absorbable sutures, the subcutaneous tissue is closed with 3-0 absorbable sutures, and the skin is closed with vertical nylon mattress sutures. A compressive dressing and an anterior-based splint are applied. No anesthetic is used locally in the incision to decrease the chance of wound healing problems. If extensive debridement is required (more than 50% of the tendon, a flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon transfer can be used for augmentation.

Rehabilitation

The amount and duration of postoperative immobilization depends on the extent of the debridement. The more structural integrity lost, the longer the immobilization should be continued. Certainly the ankle should be immobilized until the incision heals. Stitches usually are removed at 3 weeks, and a rehabilitation program is begun as soon as wound healing allows.

Insertional Tendonitis

Decompression for insertional Achilles tendon has been described using a posterior central splitting incision, a hockey stick incision, transverse incisions, an isolated medial or lateral incision, or combined medial and lateral incisions.1,8,9 We prefer an isolated lateral incision if full decompression can be accomplished through this approach; a

medial incision can be added if necessary for complete decompression.

medial incision can be added if necessary for complete decompression.

Surgical Technique

A longitudinal incision is made on the lateral aspect of the calcaneus extending proximally along the lateral aspect of the Achilles. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the sural nerve, which is very close to the surgical dissection. Sharp dissection is carried to the paratenon, and the Achilles tendon and its insertion are inspected. Any degenerative tissue is débrided as described for noninsertional tendonitis. The Haglund deformity that usually is present is isolated with a Homén retractor. Care is taken to protect the Achilles tendon insertion as well as the medial structures. A microsagittal saw is used to remove enough bone to effectively decompress the posterior prominence that contributes to the tendonitis. After adequate decompression is confirmed with a fluoroscopic lateral view, the insertion of the Achilles tendon is inspected. If the tendon is detached or is significantly weakened, two suture anchors should be used to attach it to the calcaneus in the resected area. Closure and splinting are as previously described.

Rehabilitation

Again, the amount of disruption of the tendon and its insertion determines postoperative care. If suture anchors are used, immobilization for up to 6 weeks in a cast followed by 3 weeks in a removable boot is not unreasonable. Weight bearing, range of motion, and gentle strengthening exercises are allowed in the boot.

Achilles Tendon Ruptures

Achilles tendon ruptures can occur in men or women of any age, but are most common in 30- to 40-year-old men, especially “weekend warriors,” those middle-aged athletes who play high demand sports on a recreational basis.10,11 Achilles tendon ruptures usually occur in people with no or few symptoms of tendonitis. Corticosteroid injection into or around the Achilles tendon has been implicated as a factor in spontaneous tendon rupture,6 as has the use of fluoroquinolones.

Diagnosis

Patients with Achilles tendon ruptures often describe a feeling of being shot or kicked in the back of the leg, followed by an inability to bear weight or difficulty with bearing weight. Often a palpable defect is present and the Thompson test is nonreactive.

It is important to differentiate an Achilles tendon rupture from a gastrocnemius tear or strain. A gastrocnemius tear or strain usually is more proximal, is associated with a reactive Thompson test, and can be treated nonoperatively. If the diagnosis is in question, MRI can be helpful. Plain radiographs should be obtained to identify a bony avulsion or calcification in the tendon, which can make repair more difficult. However, the diagnosis is most often based on the history and physical examination.

Nonoperative Treatment

Whether to treat Achilles tendon ruptures operatively or nonoperatively remains a matter of controversy. Advocates of nonoperative treatment cite wound healing issues and perioperative morbidity as reasons to avoid surgical treatment.12 Those who advocate operative treatment cite higher chances of rerupture, decreased range of motion, and decreased strength as disadvantages of nonoperative treatment.12,13,14 Nonoperative methods still have a definite role in the treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures, especially in elderly or high-risk patients such as those with diabetes.

Surgical Intervention

Many surgical approaches have been described for repair of Achilles tendon ruptures, some for acute tears (those that are diagnosed and treated within 6 weeks of injury) and others for chronic tears (those present longer than 6 weeks).

Repair of Acute Rupture

Although percutaneous techniques using devices have been developed, we prefer an open technique for repair of Achilles tendon ruptures. Sural nerve complications have been reported to be more frequent after percutaneous techniques.15

Open Repair

Surgical Technique

A longitudinal incision is made medial to the tendon to reduce the risk of sural nerve injury. Sharp dissection is carried directly to the paratenon, which is incised sharply and left in a position that allows it to be repaired after the tendon is repaired.

Opening the paratenon exposes the Achilles tendon rupture. Usually the Achilles tendon is torn in a jagged fashion, with frayed ends resembling the end of a mop. These ends should be freshened with a scalpel, removing just enough of the frayed tendon to achieve a clean, sharp edge; removing too much tendon increases the size of the gap to be closed. The tendon is now ready for repair. A modified Bunnell stitch is used to place two no. 2 FiberWire sutures, one in the proximal stump and one in the distal stump of the tendon. Each end of the tendon can now be securely grasped.

The suture is tied to repair the tendon while the foot is held in the same plantarflexion as the opposite foot. This mimics the resting tension of the uninjured Achilles tendon. This is a very important step to decrease the chance of weakness caused by incorrect tensioning of the Achilles tendon. If necessary, the repair can be supplemented with a horizontal mattress suture to achieve four strands across the repair, taking care not to cut the other stitches.

The paratenon is closed with 2-0 absorbable sutures. If this repair is too tight, a relaxing incision can be made in the

anterior aspect of the paratenon to allow the posterior aspect to cover the tendon without tension (Fig. 64-1). It is important to obtain a good repair of the paratenon. The subcutaneous tissue is closed with 3-0 absorbable sutures, and the skin is closed with 3-0 nylon vertical mattress sutures.

anterior aspect of the paratenon to allow the posterior aspect to cover the tendon without tension (Fig. 64-1). It is important to obtain a good repair of the paratenon. The subcutaneous tissue is closed with 3-0 absorbable sutures, and the skin is closed with 3-0 nylon vertical mattress sutures.

A Robert Jones compressive dressing is applied and an anterior-based splint is placed to hold the foot in plantarflexion to take stress off the repair. No local anesthetic is used to decrease the chance of flap necrosis. The patient is instructed to keep all pressure off the posterior aspect of the distal leg to decrease the chance of wound healing problems.

Repair of Chronic Rupture

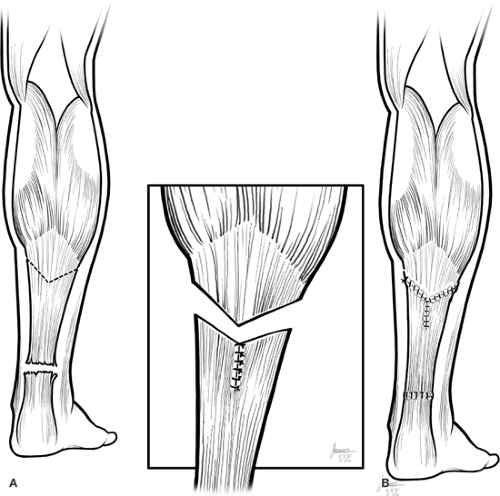

For chronic ruptures, we prefer to attempt a primary repair, but this often is not possible. If a primary repair is not attainable, we use a step-wise approach. First a V-Y advancement of the tendon is done, which usually gains approximately 3 cm of tendon length.16 If this is not adequate, an FHL transfer is added.

Surgical Technique

After exposure of the tendon as previously described, the tendon is débrided of devitalized tissue and the gap between the tendon ends is evaluated. This gap can be lessened or completely eliminated by using a grasping suture to place gentle traction on the proximal stump of the tendon for 10 to 15 minutes.

If adequate length is not obtained, a generous V-Y lengthening is done at the musculotendinous junction (Fig. 64-1A,B). The apex of the inverted V is made in the central part of the aponeurosis. The arms of the V should be at least one and one half times the length of the defect. The arms of the incision extend through the aponeurosis and underlying muscle tissue. The flap is then pulled distally until the ruptured ends of the tendons are approximated. A standard Achilles tendon repair is then done as described above. The V-Y portion is then approximated.14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree