CHAPTER 18 Technique of arthroscopic bristow-latarjet-bankart procedure: the 2b3 procedure

Arthroscopic capsulolabral repair alone results in high rates of recurrent instability in patients with glenoid or humeral bone loss, and capsular laxity, especially in young patients and those who participate in competitive contact sports.

Arthroscopic capsulolabral repair alone results in high rates of recurrent instability in patients with glenoid or humeral bone loss, and capsular laxity, especially in young patients and those who participate in competitive contact sports. The arthroscopic Bristow-Bankart is a procedure that combines the theoretical advantages of both the Bristow-Latarjet procedure and the arthroscopic Bankart repair, while mitigating the potential disadvantages of each.

The arthroscopic Bristow-Bankart is a procedure that combines the theoretical advantages of both the Bristow-Latarjet procedure and the arthroscopic Bankart repair, while mitigating the potential disadvantages of each. The coracoid bone block is passed through a subscapularis split and placed in a standing position on the glenoid neck, after which an arthroscopic Bankart repair is performed using suture anchors.

The coracoid bone block is passed through a subscapularis split and placed in a standing position on the glenoid neck, after which an arthroscopic Bankart repair is performed using suture anchors. The combined procedure provides a so-called “triple-blocking effect”:

The combined procedure provides a so-called “triple-blocking effect”:Introduction

Although the results of arthroscopic anterior labral repair using modern techniques have bewen shown to approach the success rates of open anterior stabilizations in most patients1–3 it has been recognized that it is much less effective in patients with risk factors for failure such as young age, hyperlaxity, competitive contact sport participation, and particularly severe glenoid or humeral bone loss.4–7 In such patients, coracoid transfer procedures have been shown to be more effective.8 This recognition combined with the impulse toward minimally invasive shoulder surgery and incremental improvements in technology and technique have led some surgeons to push the boundaries of arthroscopic treatment even further, developing techniques to treat severe instability with associated bone loss using arthroscopic coracoid transfer.9–11

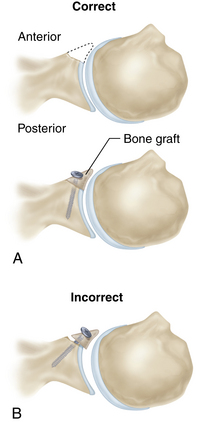

The open Bristow-Latarjet coracoid transfer has been proposed as an alternative to capsulolabral repair in patients with significant glenoid bone loss and has been shown to be a reliable technique with a very low rate of recurrent instability, a high rate of return to sports at the preinjury level, and a high rate of patient satisfaction.8,12–14 However, accurate placement of the transferred coracoid graft may be difficult because of limited exposure, especially in young muscular athletes. Misplacement of the coracoid bone block and failure of fixation are common complications that have been reported in up to 50% of patients and may compromise the results of the procedure.15,16 A coracoid bone block placed too medial or too high (over the glenoid equator) has been found to be associated with recurrent shoulder instability, while late glenohumeral osteoarthritis may result from lateral placement of the bone block.17,18

The all-arthroscopic technique that we describe combines a Bristow-Latarjet procedure with a Bankart repair while eliminating the potential disadvantages of each, allowing the surgeon to extend the indications of arthroscopic shoulder stabilization to the subset of patients with recurrent anteroinferior shoulder instability with glenoid bone loss and capsular deficiency. The procedure provides a so-called “triple-blocking effect: (1) the labral repair recreates the anterior bumper and protects the humeral head from direct contact with the coracoid bone graft (bumper effect); (2) the transferred standing coracoid bone block compensates for anterior glenoid bone loss and conforms to the glenoid concavity (bony effect); and (3) the transferred conjoint tendon creates a dynamic reinforcement of the inferior part of the capsule, both by itself and by lowering the inferior part of the subscapularis, particularly when the arm is abducted and externally rotated (belt or sling effect). Accurate arthroscopically guided positioning of the bone block in an extraarticular position may mitigate the potential for poststabilization arthritis. While the procedure is technically challenging, it is an attractive surgical option to treat patients with a previously failed capsulolabral repair where the surgical solutions are limited.

Indications/contraindications

Table 18-1 Instability Severity Index Score (ISIS) [4]

| Age at time of surgery (yr) | |

| ≤20 | 2 |

| >20 | 0 |

| Degree of sport participation (preoperative) | |

| Competitive | 2 |

| Recreational or none | 0 |

| Type of sport (preoperative) | |

| Contact or forced overhead | 1 |

| Other | 0 |

| Shoulder hyperlaxity | |

| Shoulder hyperlaxity (anterior or inferior) | 1 |

| Normal laxity | 0 |

| Hill-Sachs on anteroposterior (AP) radiograph in external rotation | |

| Visible | 2 |

| Not visible | 0 |

| Glenoid contour on AP radiograph | |

| Loss of contour | 2 |

| No loss of contour | 0 |

Score >3: Risk of recurrence 10%.

Score >6: Risk of recurrence 70%.

Description of technique

Portals

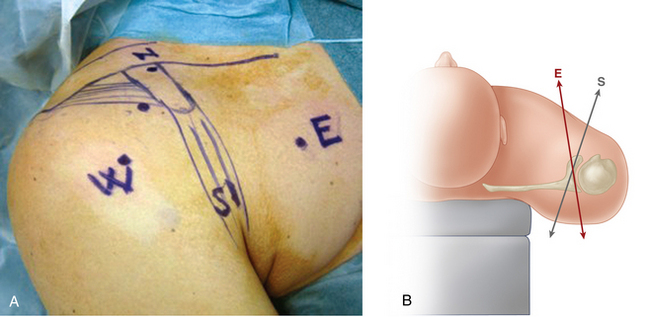

In addition to the standard posterior portal, five anterior portals are used. Their locations are carefully marked on the skin (Fig. 18-1, A). The central portal is located just lateral to the tip of the coracoid; the proximal portal (or north portal) is located above the coracoid process, just in front of the acromioclavicular joint; the distal portal (or south portal) is located in the axillary fold, three finger widths distal to the tip of the coracoid; the lateral portal (or west portal) is located two finger widths lateral to the tip of the coracoid; and finally, the medial portal (or east portal) is located three to four finger widths medial to the tip of the coracoid, passing obliquely through the pectoralis major muscle (Fig. 18-1, B). Before starting, the soft tissues (skin, fat, and deltoid fascia) are elevated from the coracoid process and conjoint tendon by injecting 10 mL of Xylocaine with adrenaline.

Pearl: The Medial East Portal

The east portal is used initially as a working portal to expose the coracoid and later to retract the osteotomized coracoid bone block medially; however, its principal function is to advance the screw that fixes the bone block to the glenoid, and it is this function that necessitates placing it medial to the coracoid process. If the portal is made more laterally, its trajectory will not allow fixation of the bone block flush with the articular surface and will oblige an overhanging position (Fig. 18-2). A cadaveric study on the safety of the east portal demonstrated that as long as the trajectory was kept anterior to the conjoint tendon, all neurovascular structures were at least 1 cm away.19

Procedure

Step one: glenoid preparation and drilling

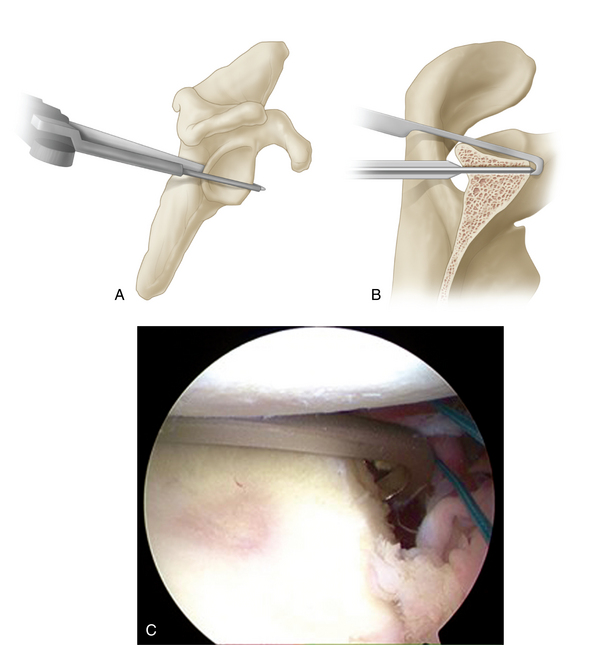

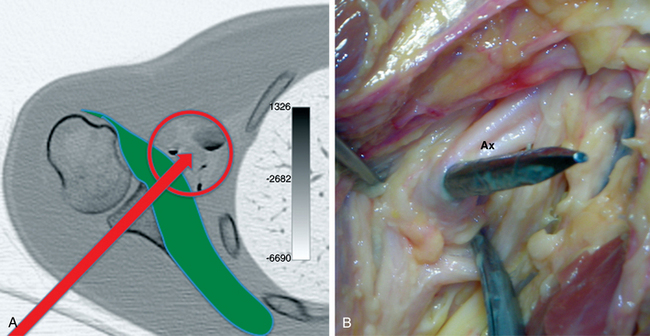

The arthroscope is then switched to the anterior central portal. A specific guide (glenoid guide, Smith & Nephew, USA), introduced through the posterior portal, is used to insert a guide pin through the glenoid neck from posterior to anterior. The glenoid guide is angled 15 degrees from medial to lateral and has a stop at the distal end to prevent overpenetration of the guide pin (Fig. 18-3, A, B). The guide pin is made of two parts: a female part (2.5 mm in diameter) and a male part (1.5 mm in diameter). The guide pin should penetrate the glenoid neck anteriorly below the equator (at 5 o’clock) and 3 mm medial to the glenoid surface (Fig. 18-3, C). The drilling depth is measured using the glenoid guide. Before leaving the glenohumeral joint, the Subscap Spreader (Smith & Nephew, USA) is introduced through the posterior portal and pushed through the subscapularis muscle (under the labrum) to act as a landmark for the subscapularis split that will be performed later.

Glenoid Drilling Pearl: The Importance of Screw Trajectory

Drilling the screw hole is a potentially dangerous step, as the correct trajectory for the drill places the brachial plexus and associated vessels at risk anterior to the glenoid neck. A cadaveric study demonstrated that the correct trajectory for placing the glenoid screw passes directly through the brachial plexus (Fig. 18-4).19 For this reason drilling the glenoid arthroscopically from anterior to posterior is not advisable because it is not possible to retract the neurovascular structures medially as is done in an open Bristow-Latarjet procedure, and the surgeon is therefore forced to use a drill trajectory that diverges from the axis of the glenoid surface to avoid the medial neurovascular structures. The result is a bone block that overhangs and exaggerates the convexity of the glenoid and may lead to later arthrosis, particularly if the bone block is placed intra-articularly (see Fig. 18-8, B). For this reason, the glenoid should be drilled from posterior to anterior, using a stop at the tip of the drill guide to prevent overpenetration of the drill, thus avoiding injury to the anterior neurovascular bundle (see Fig. 18-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree