Chapter 9 Tai Chi

Initial Examination

Initial Examination

Client Goals: Improve her balance and sense of confidence performing daily activities

Cardiovascular and Pulmonary: Vital signs at rest: heart rate (HR) 88; blood pressure (BP) 126/82

Timed Up and Go (TUG): 11 seconds; TUG Manual: 14 seconds

Berg Balance Scale: 52/56 total score. She received 4/4 on the first 11 items of the test. On item #12 alternate stool step, she scored 3 of 4 (completed 8 steps in >20 seconds); item #13 tandem stance scored 3 of 4 (placed feet in semi-tandem position); item #14 one-limb stance scored 2 of 4 (one leg standing time, or OLST >3 seconds)

Reevaluation

Reevaluation

Rose is in good health and until recently was fairly active, exercising regularly. She does have a history of falling, which could possibly be an isolated incident resulting from an environmental hazard. A difference at least 4.5 seconds for the TUG vs. TUG Manual score is associated with a greater likelihood of falls.1 This client has only a 3-second difference on the dual task. For many older adults, polypharmacy is a risk factor for falls, but this is not an issue for Rose.

However, some of her other scores on the balance tests signal that she may be at risk for falls. Newton2 reported the following average values for community-dwelling older adults: forward reach 9 inches, lateral reach 6 to 7 inches, backward lean 4½ to 5 inches. This client’s reach scores are all below reported averages. In addition, a forward reach of less than 10 inches has been associated with an increased likelihood of falls.3 Likewise, the Berg Balance score, a reliable measure of balance during performance of functional tasks, is predictive of fall risk in community-dwelling older adults.4 Shumway-Cook et al6 reported that for Berg scores between 56 and 54, each one-point drop was associated with a 3% to 4% increase in fall risk. For Berg scores between 54 and 46, however, each one-point change in score was associated with a 6% to 8% increase in fall risk. In addition, the strongest predictor of falls was the combination of Berg score and a self-report of imbalance. Finally, her self-perception and fear of falling alone is a risk factor.

The decreased LE strength and decreased ankle range of motion may be factors that contribute to an inability to generate an effective recovery strategy in response to a loss of balance. Given the above findings, Rose appears to fall under the Neuromuscular Practice Pattern 5A: Primary Prevention/Risk Reduction for Loss of Balance and Falling, according to the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice.5

Tai chi has been practiced in China for centuries as a means to enhance health, fitness, and longevity for people of all ages.6,7 This chapter addresses the use of tai chi as a mind-body intervention. In particular it focuses on the use of tai chi as an adjunct to wellness and fall prevention for a community-dwelling older adult. A variety of age-related changes in the neuromuscular system may put older adults at risk for falls. The potential impact of tai chi on these changes is presented.

INVESTIGATING THE LITERATURE

The therapist has read a few articles in the literature related to falls in the elderly and use of tai chi as a mechanism to improve balance. Given the results of the initial examination and the client’s interest in tai chi, the therapist decides to investigate the available information and evidence. The therapist uses two strategies to investigate the literature. The first is a detailed approach in which preliminary background reading is performed on tai chi and balance. This is followed by a search of the databases and evaluation of the literature with use of review articles and primary sources of research related to tai chi and balance. The second is the use of the PICO format for a focused search to answer the clinical questions generated by the case.

Preliminary Reading

Tai chi has its origins in Chinese martial arts, and numerous books exist in the popular media on the topic. The majority of books provide background information regarding the origin, philosophy, and potential benefits of tai chi. Most provide photos or diagrams of the various movement patterns, or forms, of tai chi. For example, Chaline’s8 presentation of the 24-step simplified tai chi includes pictures of the step-by-movements for each individual form, in addition to photos of the complete sequence. A few examples of books that may be particularly helpful to the health professional interested in learning more about tai chi or in providing resources to clients seeking to promote health and wellness are: Chaline’s Tai Chi for Body Mind and Spirit,8 Hooton’s Tai Chi for Beginners,9 Carradine’s Tai Chi Workout,10 Liao’s The Essence of T’ai Chi,11 Yu’s Tai Chi Mind and Body,12 and Yu and Johnson’s Tai Chi Fundamentals: Health Care Professionals and Instructors (see Chapter 7).13

Philosophy and History of Tai Chi

Tai chi’s underlying philosophy is based in Taoism and is described in the following quotation: “Tai chi is infused with the spirit of the Tao—the Way. Life is a never-ending journey—a process in which we must always seek to balance the opposite forces of yin and yang to find fulfillment and happiness”8 (p. 7). One of the basic principles underlying tai chi exercise is the Chinese concept of qi (or chi), which is a life force or energy that flows through the body. If an imbalance or blockage of qi exists, then injury or illness results. Tai chi also is based on the theory of yin and yang, or the theory of opposites.8,10,11 The yin and yang symbol represents the balance between opposites. Yin, the negative power, represents yielding, whereas yang, the positive power, represents action. These two powers oppose yet complement each other. Other examples of complementary opposites include masculine/feminine, light/dark, and hard/soft (see Chapter 4).6

In China, tai chi has been used to enhance health, fitness, and longevity for people of all ages.6,7 It is characterized by a series of movements, or forms, linked together in smooth continuous motions, with an emphasis on weight shifting and posture control. The combination of mental concentration on movements and diaphragmatic breathing promotes harmony between mind and body. Breathing, meditation, and movement com-bine to facilitate the smooth flow of qi throughout the body. Tai chi often is called “meditation in motion.”8,10

Several styles of tai chi exist, with five main schools each named after their respective founding family: Chen, Yang, Sun, Wu (Jian Qian), and Wu (He Qin). Some use more of a martial arts style. Yang style, with its relaxed and evenly paced movements, often is considered the most gentle and suitable style for older adults.1 Yang style and its variations have been used in the majority of medical and behavioral research on tai chi. Within Yang style are long and short versions with 24, 48, 88, and 108 forms. The simplified 24-step form is one of the most widely practiced styles today (Figure 9-1).6,8

Overview Articles

In addition to the information available in the popular media, the therapist reads several articles from the professional literature that provide an overview of tai chi, in addition to general background information about history, philosophy, and a summary of the available literature.6,7,14–16 One article in particular provided useful information in the choice of the type of intervention to use for this client.6

Also in the literature were a number of summary or overview articles related to reduction of falls or postural instability in the elderly. Many of these mentioned the tai chi literature or recommended inclusion of tai chi as one intervention to achieve these aims. For example, Skelton and Dinan16 provided a summary of the literature plus a detailed description of a protocol that included tai chi as one element of a multidimensional program designed to reduce postural instability in older adults. Given this general background information, the therapist decides to search the professional literature for more details.

Searching the Databases

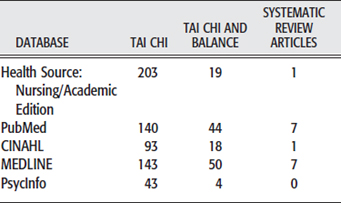

An initial search of MEDLINE using the term tai chi reveals 143 journal articles, 29 items in the books/AV category, and 159 items in the consumer health category. Because of the widespread availability of resources about tai chi, the therapist decides to limit searches to full-text, English, and journal articles only and searched the following databases: CINAHL, PubMed, MEDLINE, and PsycInfo (Table 9-1). Because of the interest in tai chi among nursing and other health professionals, the therapist also searches HealthSource: Nursing/Academic Edition. Using the key word tai chi generated a combined total of 622 citations; however, because of considerable overlap of PubMed and MEDLINE, use of only the number of citations from MEDLINE yielded a more accurate representation of a combined total of 482 citations. A scan of titles reveals that the literature reports use of tai chi for a variety of purposes, including health promotion, improving balance, reducing stress, enhancing emotional well-being, and cardiovascular effects. For example, in MEDLINE she finds 26 articles related to tai chi and cardiovascular system effects, 50 related to balance and falls, five related to effects on osteoporosis and/or menopause, and nine related to a variety of other disorders such as cancer, fibromyalgia, substance abuse, sleep disorders, dementia, head injury, and multiple sclerosis. So the therapist decides to narrow the search to address her primary interests by using the key words tai chi and balance.

From CINAHL she scans 18 titles from combined search terms of tai chi and balance, selecting seven articles of interest, and omitting newsletters from various health-related organizations. After she reviews these selected titles, she omits two additional citations for similar reasons. Finally, omitting duplications from the other databases yields two citations of interest unique to CINAHL.

After eliminating duplicates among databases, the therapist’s search totals 54 articles, including seven systematic reviews,17–23 five summary or overview articles, 20 primary sources, and a variety of clinical reports related to the areas of interest. Of the primary studies, seven were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), four were intervention studies, and nine were cross-sectional studies.

EVALUATING THE LITERATURE

Evidence supports beneficial effects of tai chi on cardiac, respiratory, and musculoskeletal function; postural control; and the reduction of falls in the elderly.19,22 The most relevant findings from the review of the literature are presented in the following sections.

Community-Dwelling Older Adults

Prevention of Falls

Approximately 30% of adults age 65 and older fall each year.23 Falls may have serious consequences, including fractures and other injuries, which in turn may have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality. As a result, a great deal of information in peer-reviewed literature investigates prevention of falls in older adults. This includes three systematic reviews of the literature that investigate the effectiveness of various interventions in reduction of the number of falls in community-dwelling older adults.17,18,20 Among interventions determined “likely to be beneficial” were a 15-week tai chi group exercise intervention and a program of muscle strengthening and balance retraining that was prescribed by a health professional.17,18,20,24 The support for tai chi was based on the evidence from one randomized clinical trial25 with 200 participants (risk ratio of 0.51, 95% confidence interval 0.36-0.73). This was a grade B recommendation,20 which means that strong evidence was found from at least one level II randomized trial with an adequate sample size.

In addition, four systematic reviews focused specifically on the effectiveness of tai chi.19,21–23 All agreed that evidence exists to support the ability of tai chi to reduce falls in community-dwelling older adults. However, their findings were somewhat less favorable than the conclusions of the previously mentioned reviews17,18 in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (see Chapter 2). This was due to concerns that the impact of tai chi on falls was based on the results of only one study. Wu23 and Verhagen et al21 acknowledged that the findings of the study by Wolf et al25 were significant. However, they concluded that limited evidence exists that tai chi was effective to reduce falls in the elderly.

The hallmark study cited in each of these systematic reviews was part of the Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques (FICSIT) studies, which were a preplanned, multicenter trial of various interventions to reduce frailty and falls in older adults. As part of this larger in-vestigation, Wolf et al25 conducted a trial with 200 subjects randomly assigned to one of three groups for a 15-week intervention: tai chi exercise, computerized balance training, or an education control group. Participants were community-dwelling older adults over age 70 (mean 76.2). The tai chi group met twice a week and practiced 10 “forms” drawn from the original 108-form Yang style tai chi. The tai chi group experienced fewer falls than other groups (56 in tai chi group, 76 in computer training, 77 in control) and reduced their risk of multiple falls by 47.5%.25

In summary, two systematic reviews consider that tai chi is likely to be beneficial in reduction of falls, based on the results of one well-designed RCT. The five remaining systematic reviews acknowledge the importance of the results of this single study but caution that additional evidence from RCTs is needed to strengthen the support for tai chi. Because these systematic reviews were published, an additional RCT by Li et al26 found that a 6-month, three-times-per-week program of tai chi significantly reduced the frequency and risk of falls in older adults. As of yet, the mechanism of the benefits is not well understood.

Reduced Fear of Falling

In addition to the impact on actual number of falls, participation in tai chi also appears to reduce the fear of falling among older adults.26–28 In a later study by Wolf et al27 tai chi participants reported reduced frequency of fear of falling (56% to 31%) after a 15-week program. Based on these results, the systematic review by Wu concluded that some evidence supports a positive effect of tai chi on prevention of falls in addition to the reduction of the fear of falling.23

In 2001 Li et al29 examined whether a 6-month program of tai chi improved self-reported physical function as measured by the Short Form General Health Survey (SF-20). The researchers randomly assigned 94 physically inactive community-dwelling adults (mean age 72.8) to a tai chi or waiting list control group. The 24-form Yang style tai chi exercise took place twice a week. Results indicated significant improvements in all aspects of physical function for tai chi participants versus the control group. Participation in tai chi was associated with reduced self-report of physical function limitations. In a separate publication with the same subjects,30 older adults in the tai chi group reported increased self-efficacy, with the amount of change in self-efficacy associated with higher levels of attendance at the sessions. In addition, participation in tai chi led to an increased self-report of physical activity and self-efficacy among older adults.

Improved Balance Performance on Computerized Tests

Yan31 also reported that an 8-week program of tai chi resulted in greater improvements in dynamic balance control of 28 nursing home village residents when compared with 10 residents who participated in a walking or jogging program. Dynamic balance control was measured on a stabilometer platform. Although the results appear promising, they must be viewed with caution because participants were permitted to self-select in which type of exercise program they would participate. The authors suggested that the movement experience of performing tai chi enhanced balance control; more efficient use of proprioceptive feedback to determine their center of mass and maintain stable position contributed to improved dynamic balance control.

Tsang and Hui-Chan32 examined the effect of an intensive tai chi training program that consisted of 90-minute sessions six times per week for 8 weeks. Elderly participants in tai chi (n=24) demonstrated improved balance control during dynamic posturography testing versus the education control group (n=27). In addition, the improvements were maintained at follow-up testing 4 weeks post intervention. The researchers noted that after week 4, the balance performance in the experimental group was comparable to that of experienced tai chi practitioners, which led to their conclusion that as little as 4 weeks of intensive tai chi practice resulted in improved balance in elderly subjects. Once again, the results must be viewed with caution because whether groups were selected by participants or randomly assigned is unclear.

A follow-up investigation of a 72-person subset of the original 200 participants in the FICSIT trial who were less active27 revealed that computerized balance training resulted in reduced postural sway during computerized post-tests, but participation in tai chi did not. Instead, older adults who participated in tai chi responded to dynamic perturbations with more sway during the post-tests. The authors suggested that this response indicated better balance control because participants were able to move more easily toward their limits of stability on the computerized tests. This was supported by the finding that the tai chi group reported less fear of falling after the 15-week intervention than individuals who participated in computerized balance training.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Plan of Care

Plan of Care