Surgical Treatment of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Catherine M. Curtin

Amy L. Ladd

DEFINITION

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a compression neuropathy of the ulnar nerve that occurs at or around the level of the elbow (cubis is Latin for “elbow”).

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common compression neuropathy of the upper limb requiring treatment after carpal tunnel syndrome.

ANATOMY

The ulnar nerve is the terminal branch of the medial cord of the brachial plexus, with contributions between C8 and T1 nerve roots.

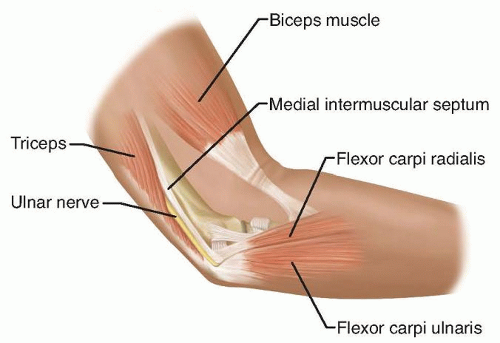

The ulnar nerve traverses the cubital tunnel, a fibro-osseous tunnel at the elbow. The medial epicondyle, the olecranon, the medial collateral ligament of the elbow (which forms the floor), and the fibrous retinaculum extending from the medial epicondyle to the olecranon make up the anatomic landmarks (FIG 1).13

Any of several possible sites of compression of the ulnar nerve around the elbow can result in cubital tunnel syndrome. All of these sites should be considered when selecting the type of surgical decompression.

The arcade of Struthers is a controversial site of compression because it is found in only a minority of patients. If present, it is found approximately 8 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and consists of a fascial band running from the medial head of the triceps to the intermuscular septum.17

The medial intermuscular septum is a fascial band from the coracobrachialis to the medial humeral epicondyle, especially thick at its attachment to the epicondyle. The ulnar nerve may rest or scissor over the septum as it crosses from the anterior to the posterior compartment, as it approaches the medial epicondyle, or after an anterior transposition if it is not adequately excised.

The arcuate ligament of Osborne at the cubital tunnel, which is the fibrous band extending from the medial epicondyle to the olecranon, can cause stenosis of the cubital tunnel and, thus, ulnar nerve compression.

Distally, the nerve can be compressed as it passes between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), especially if each muscle head from the medial epicondyle and the olecranon converge close to the elbow joint.

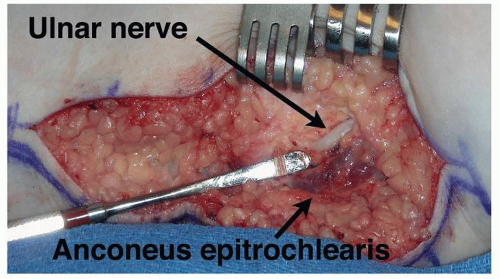

The presence of an anconeus epitrochlearis (FIG 2), an anomalous thin muscle extending from the triceps or olecranon to the medial epicondyle, also can cause ulnar nerve compression.

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and the medial brachial cutaneous nerve both emanate directly from the medial cord and are thus not ulnar nerve branches, but they importantly may lie in the surgical field. They are usually found deeper than expected, along the fascia of the triceps, brachialis, and FCU.

PATHOGENESIS

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a compressive neuropathy. Several anatomic factors make the ulnar nerve susceptible to compression at the elbow.

The nerve is superficial at the level of the elbow, making it susceptible to minor and major trauma, ranging from mild repetitive contusion to high-energy injury.

The bony tunnel and its soft tissue support between the olecranon and medial epicondyle may be shallow, either inherently or traumatically, promoting subluxation, “perching” on the epicondyle, and microtrauma.

FIG 2 • An anomalous anconeus epitrochlearis encountered overlying the cubital tunnel. Anterior is at top and posterior at bottom; the forearm is to the left.

Elbow flexion increases pressure on the nerve and decreases the volume of the cubital tunnel, resulting in compression of the nerve.7

NATURAL HISTORY

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Subjective complaints include numbness in the small and ring fingers, often with accompanying burning pain around the medial epicondyle. Symptoms may be worse at night.

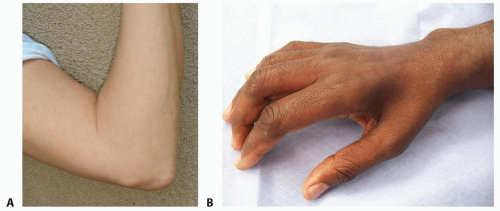

As the disease progresses, patients may complain of weakness or clumsiness of their hands. More advanced disease will demonstrate wasting of the intrinsics and clawing of the ring and small fingers.

Systemic diseases such as diabetes, amyloidosis, or alcoholism may cause peripheral neuropathy, which can mimic the symptoms of a compressive neuropathy.

A smoking history is important not only for impaired vascularity but because it may point to the rare Pancoast tumor, an apical lung tumor, which causes plexus compression, mimicking the symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome.

Elbow trauma can create deformity, causing ulnar nerve compression. Deformities include a cubitus valgus, cubitus varus, or malunion. The elbow trauma can be remote and result in tardy ulnar nerve palsy.

Look for atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand or a clawed posture of the ring and small fingers. Check for masses around the elbow.

Palpate the elbow and hand to evaluate for tender masses or other anomalous elbow anatomy.

Put the elbow through its range of motion and assess whether the ulnar nerve subluxates or perches at the medial epicondyle with elbow flexion (FIG 3A).2

Visible atrophy of the first dorsal interosseous nerve correlates with significant ulnar nerve compression and can indicate significant motor impairment (FIG 3B).

Perform a sensory examination of the hand, using Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments to obtain threshold measurements. Evaluate sensation on the ulnar dorsum of the hand. If sensation is normal, it suggests the problem may be distal, at the level of Guyon canal.

Clinical tests that can help with diagnosis include the following:

Tinel test. This test may not be specific because many normal individuals will have a positive Tinel response to percussion.

Elbow flexion test. This test is sensitive for cubital tunnel syndrome.

Scratch collapse test can help localize the site of compression.3

Crossed finger test. This test demonstrates weakness of dorsal and palmar interossei.

Froment sign. A positive Froment sign indicates weakness of the adductor pollicis.

Wartenberg sign (in which the small finger assumes an abducted posture with finger extension). This sign is the result of weakness in the palmar interossei, resulting in unopposed ulnar pull of the extensor digiti quinti.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

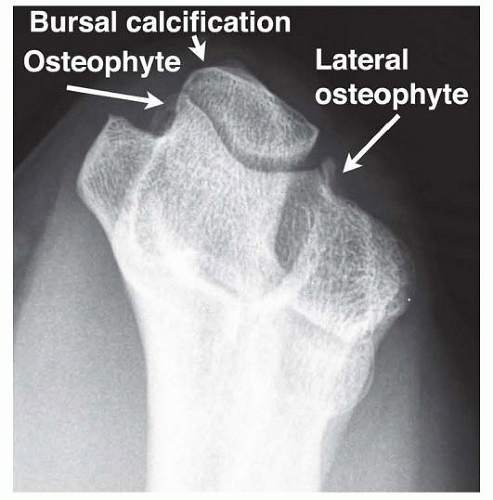

Radiographs of the elbow define the bony architecture and its alterations: masses, erosions, arthritis, and previous trauma. An axial view is helpful to evaluate the cubital canal (FIG 4).

Normal results on electrodiagnostic studies (eg, nerve conduction and electromyography) do not exclude the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome; the syndrome may be present but not severe.

These tests localize the area of compression if the nerve conduction is measured at short segment intervals.

Several positive electrodiagnostic findings suggest ulnar compression:

Motor conduction across the elbow less than 50 m per second15

Focal slowing of nerve velocity across the elbow

Fibrillation potentials or positive waves suggest axonal degeneration, representing a poorer prognosis for complete recovery.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) may occasionally be helpful as ancillary imaging studies to define soft tissue aberrancies and localize bone abnormalities such as osteophytes in the cubital tunnel.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Cervical spine disease affecting C8 and T1

Compression of the inferior aspect of the brachial plexus from shoulder trauma

Apical lung tumor (Pancoast tumor)

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Entrapment of the ulnar nerve at the wrist (Guyon canal)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Activity modification

Ulnar nerve protection limiting microtrauma to the nerve through elbow padding and limiting direct pressure on the nerve

Minimize prolonged elbow flexion, especially at night, through sleep modifications or splints.

Splinting

Splints to prevent elbow flexion; rigid splints are more effective but are less tolerated by patients. If persistent paresthesias exist, a trial of temporary full-time use is recommended. For milder cases, the splint is worn only at night.4

Nonoperative treatment requires a trial of several months before determining its success.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical intervention should be considered for patients presenting with motor involvement or permanent sensory changes or for those who have failed nonoperative treatment.

Preoperative Planning

Review the history and physical examination.

Review plain radiographs for evidence of old trauma, valgus or varus deformity, or loose bodies.

Electrodiagnostic testing and examination may correlate with postoperative results.

A patient with a visible and symptomatic subluxating nerve may be considered for a medial epicondylectomy or transposition.

Patients with severe disease with muscle wasting are less likely to have complete recovery.10

Positioning

The patient usually is placed in the supine position.

If a sterile tourniquet is preferred, drape out the forequarter. A standard tourniquet may be used, but position it high in the axilla, with good padding. A proximally placed tourniquet can be challenging to position in the obese arm in either circumstance because the tourniquet tends to gap distally. It is worth the extra time to position it properly because adequate hemostasis and visualized proximal dissection are important aspects of ulnar nerve surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree