Surgical Technique: Metal on Metal Hip Resurfacing

Edwin P. Su

Hip resurfacing is well-known to involve a learning curve, because of the differences in the technique as compared to total hip replacement (THR) (1,2,3). The distinctions in surgical technique when compared to THR include the necessity of preparing the acetabulum with the femoral head and neck still intact, and the goal of sculpting the femoral head to accept the resurfacing femoral implant. These essential elements of the operation can pose challenges to even the most experienced of hip surgeons and require specialized training.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 55-year-old active male, who has been experiencing progressive left hip pain for 3 years. Despite physical therapy, activity modification, and weight loss, he continues to have debilitating pain that now limits his daily activities. On examination, he has an abductor lurch when ambulating. His left hip has pain with passive range of motion: flexion to 100 degrees, internal rotation to 0 degrees, external rotation to 40 degrees, abduction to 35 degrees, and adduction to 0 degrees.

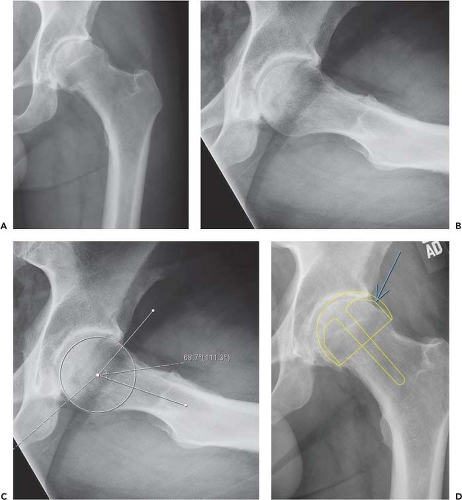

His radiographs demonstrate superolateral joint space narrowing, with sclerosis and osteophyte formation (Fig. 68.1A). His bone quality looks excellent, based on his cortical indices. On the extended neck lateral view (Fig. 68.1B), an anterosuperior cam protuberance can be seen; his alpha angle measures approximately 70 degrees (Fig. 68.1C).

Indications

Many studies have found, through registry and clinical studies, the ideal patient demographic for hip resurfacing to be of male gender and young age (4,5,6). Male gender is likely a surrogate for larger bone size and therefore larger implant sizes, which appears to be beneficial for wear properties of the metal-on-metal bearing. The cutoff point for implant size, according to the Australian National Joint Registry, is a femoral head size of 50 mm and larger (4). Furthermore, primary osteoarthritis is the prime indication, as opposed to diagnoses of dysplasia or osteonecrosis, which have been found to have less favorable results. Bone quality is thought to be important, because of the need of the proximal femoral bone to support the resurfacing implant (7). It is well-known that hip resurfacing cannot alter the proximal femoral geometry as much as THR, and thus cannot correct excessive leg-length discrepancies (8). Therefore, the ideal indication for hip resurfacing is a male patient with primary osteoarthritis, under the age of 65, with good bone quality and relatively normal proximal femoral geometry.

This demographic of patient often has an underlying anatomic disturbance in the form of cam impingement leading to femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). In this deformity, the femoral head is posteriorly and medially rotated with regard to the femoral neck, leading to decreased offset anteriorly and superiorly. Our case illustration exhibits this pattern of morphology, more easily seen on the extended neck lateral x-ray (Fig. 68.1B,C). It is important to recognize this anatomic configuration preoperatively as it should influence the placement of the femoral resurfacing implant, to be discussed in the surgical technique portion of this chapter.

Contraindications

The absolute contraindications to hip resurfacing have to do with the metal-on-metal bearing currently used for all resurfacing implants. Good renal function is essential for excreting the cobalt and chromium ions that will be present in the circulating, peripheral blood. Therefore, patients with compromised renal function posed an absolute contraindication to hip resurfacing, as these patients will not be able to adequately clear the metal ions from the body. Conditions that may lead to renal compromise, such as diabetes mellitus and systemic lupus erythematosus, have to be considered carefully, as these patients may experience a rise in circulating metal ions as their renal function declines. Patients with a known allergy to one of the metal constituents

of the resurfacing implant also are contraindicated from the procedure.

of the resurfacing implant also are contraindicated from the procedure.

Other relative contraindications have to do with the bony structure; osteoporosis and osteopenia may lead to a greater risk of femoral neck fracture. Dysplasia with excessive anteversion is also a relative contraindication, as the abnormal rotational anatomy may lead to edge loading and excessive production of metal debris.

Operative Technique

Templating

Preoperative templating is an important foundation of the surgical technique, as the head and acetabular implants in hip resurfacing are coupled together by a defined size relationship. Most resurfacing systems have a 6-mm difference

between the inner and outer diameters of the acetabular component; therefore the femoral head diameter is 6 mm smaller than the acetabular diameter. Planning for placement of the hip resurfacing implants must be carried out with this relationship in mind. Specifically, too small of a femoral implant should not be selected if this would cause the acetabular component to be of inadequate size to achieve fixation; conversely, too small of an acetabular component could lead to a femoral head size that is too small which can lead to notching of the femoral neck.

between the inner and outer diameters of the acetabular component; therefore the femoral head diameter is 6 mm smaller than the acetabular diameter. Planning for placement of the hip resurfacing implants must be carried out with this relationship in mind. Specifically, too small of a femoral implant should not be selected if this would cause the acetabular component to be of inadequate size to achieve fixation; conversely, too small of an acetabular component could lead to a femoral head size that is too small which can lead to notching of the femoral neck.

With regard to implant position, the acetabular component should be placed in the anatomic position with sufficient coverage to support a socket without adjunctive screw fixation. Inclination angle is targeted around 40 degrees to achieve a good arc of coverage. The femoral implant should be placed so that the stem is central within the femoral neck in both the coronal and sagittal planes, and the cylindrical portion of the head should contact bone circumferentially. That is, there should not be any gaps between the cylindrical portion of the femoral implant and the native bone. A valgus neck–shaft angle is preferable to a varus angulation; however, this desire for improved biomechanical forces upon the neck must be balanced by the tendency to notch the superior femoral neck with increasing valgus angles. Often, if the patient has a preoperative cam-type deformity, the femoral implant will appear to be offset superiorly and anteriorly compared to the native femoral head (Fig. 68.1D). This is the preferred position so that the head–neck offset will be corrected by the implant being placed centrally upon the neck.

Exposure

The exposure necessary to perform hip resurfacing is larger than that of a THA because of the retention of the femoral head and neck. To be able to visualize the socket while the head and neck are still intact requires a larger incision and capsular releases. Currently, most hip resurfacings are performed via a posterior approach, but there are good results when performed through direct lateral, anterior, or surgical dislocation approaches as well. The main requirement for any approach is the ability to mobilize the femoral head and neck enough to visualize the head/neck junction circumferentially, and to be able to “tuck” the femoral head and neck out of the way during acetabular preparation. In this chapter, I will be discussing the posterior approach and the tips to gain adequate exposure.

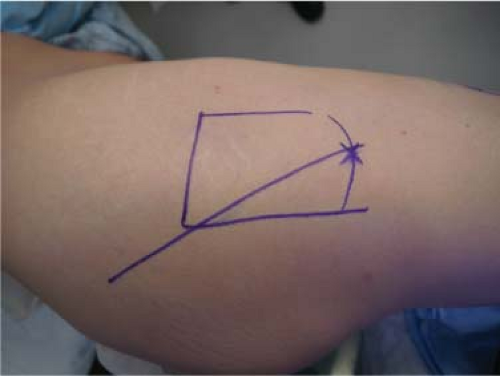

The patient is positioned in the lateral decubitus position. The bony landmarks are palpated and the tip of the greater trochanter is marked. The midpoint of the femur at the level of the vastus ridge is marked and an incision connecting this point to the posterolateral tip of the trochanter is made (Fig. 68.2). Generally the incision length will be between 5 in and 8 in long; it can be extended during various points in the procedure if visualization is inadequate. This incision is typically more posterior than for a THA because the femoral head will be rotated into this portion of the incision during femoral preparation.

I typically release a portion of the gluteal sling in all patients (Fig. 68.3) as there is some evidence that this may protect the sciatic nerve from compression during rotation of the hip (9). It also allows for greater translation and rotation of the femur. After detachment of the short external rotators, the capsule is exposed. A plane between the gluteus minimus and the capsule is developed using a periosteal elevator to a greater degree than with THA, as the gluteus minimus needs to slide when tucking the femur anteriorly during acetabular preparation. For the capsulotomy, I typically perform a “modified posterior approach” where the incision is performed along the femoral head with sharp dissection rather than detaching the capsule from the lateral neck with cautery (Fig. 68.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree