Surgical Repair and Reconstruction of the Lateral Ulnar Collateral Ligament

Bernard F. Morrey

Joaquin Sanchez-Sotelo

INTRODUCTION

In instances of complete elbow dislocation, it is now accepted that the essential lesion is disruption of the ulnar part of the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL) complex (1,2). The medial collateral ligament is also involved with complete dislocation (3,4), but failure of healing occurs far more often with the lateral, rather than the medial, ligament. Residual symptomatic instability is rotatory in nature (3,5) with the earliest sign being posterior subluxation of the radial head on the capitellum (Fig. 29-1).

ETIOLOGY

Posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) of the elbow is almost always due to a traumatic event. This may be either because of inadequate healing of an acute disruption or due to inadequate repair at the time of surgery to address an acute injury or residual pathology (5,6 and 7). The problem can also be caused by violation of the LUCL during lateral release for lateral epicondylitis or with radial head excision or fixation.

PATHOANATOMY

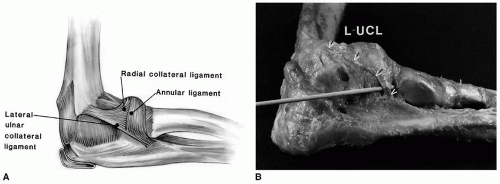

The lateral ligament complex is variably illustrated but not precisely recognized or defined in some anatomy textbooks (8,9 and 10). The portion of the lateral complex that originates at the lateral condyle and inserts onto the supinator crest was described in 1984 along with its significance (Fig. 29-2) (1). Since the ligament is obscured by the supinator muscle, its presence has not been previously appreciated (2). Cadaveric experiments subsequently clearly demonstrated this was the essential stabilizer of the elbow in preventing PLRI (5). The presence of the structure can be confirmed by placing a finger on the tubercle of the supinator crest and exerting a varus stress to the elbow. The insertion of the ligament will be palpated to become taut with this maneuver. Appreciating the

anatomic origin and insertion and function of the ligament is the essential factor in the preoperative planning process (13).

anatomic origin and insertion and function of the ligament is the essential factor in the preoperative planning process (13).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Most patients have a history of injury, possibly a dislocation, with residual symptoms of pain and catching, or sometimes, the patient is aware of instability. Similarly, these symptoms may follow surgery and are described as different from the pain that had prompted the prior procedure.

DIAGNOSIS

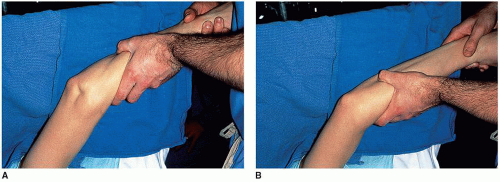

This is made by a careful clinical assessment. The original description of the condition included the posterior lateral rotatory pivot shift test of the elbow (5). Similar to the examination of the knee for anterior cruciate ligament deficiency, and modified from the original description, the test consists of placing the patient supine, flexing the shoulder and elbow to 90 degrees, and exerting a valgus,

supination force while extending the elbow. The elbow will slide into the subluxed position with a dimple at the lateral elbow as joint approaches about 30 degrees of extension (Fig. 29-3). With flexion, or possibly with simple pronation, the joint is reduced, which is easier to appreciate than the initial subluxation.

supination force while extending the elbow. The elbow will slide into the subluxed position with a dimple at the lateral elbow as joint approaches about 30 degrees of extension (Fig. 29-3). With flexion, or possibly with simple pronation, the joint is reduced, which is easier to appreciate than the initial subluxation.

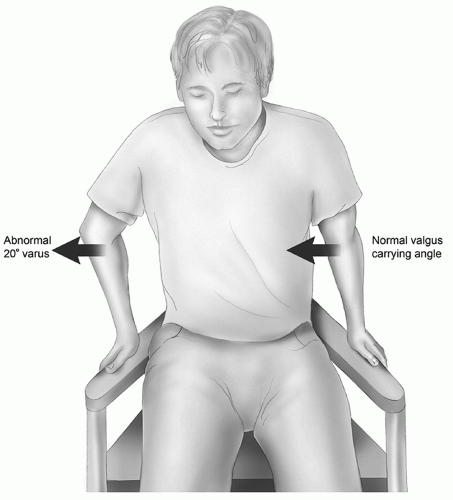

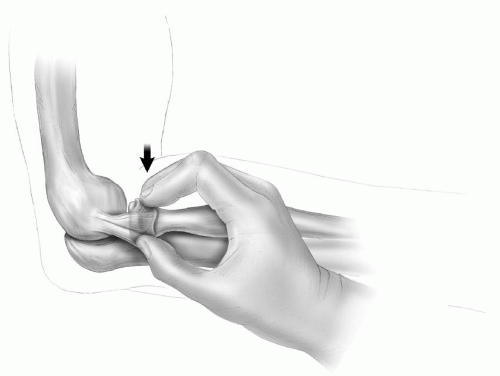

Since this is painful, and often not demonstrable in the clinic, more simple and reliable tests have evolved. Currently, the most readily performed and reliable diagnostic maneuver is to ask the patient to use the arms when rising from a chair (Fig. 29-4) (11). This reproduces the symptoms or may actually demonstrate the subluxation if the office. I have found that placing the elbow at 90 degrees of flexion, and grasping the radial head between the fingers while gently applying a downward force, similar to a posterior drawer test of the knee, allows the examiner to sense posterior luxation of the head on the capitellum if this is present (Fig. 29-5). In those patients with symptoms

strongly suggestive of instability but a poor history or otherwise lack of clear demonstration of the problem, arthroscopy may reveal an excessive degree of widening of the ulnohumeral articulation with forced supination or widening of the lateral ulnohumeral joint.

strongly suggestive of instability but a poor history or otherwise lack of clear demonstration of the problem, arthroscopy may reveal an excessive degree of widening of the ulnohumeral articulation with forced supination or widening of the lateral ulnohumeral joint.

Imaging

As would be expected, the MRI is the most commonly ordered image to assist in making the diagnosis. We do not employ this adjunct as the signal may be abnormal in a healed injury. However, if positive, one can be assured of prior injury, even if its true relevance is not revealed. Varus stress may show some laxity, and this is performed under fluoroscopy and is the imaging study of choice (Fig. 29-6).

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The first step is to have a clear understanding of the pathology and anatomy as described above.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree