Surgical Release and Reconstruction for Digital Syndactyly

Carley B. Vuillermin

Peter M. Waters

Syndactyly is the failure of the separation of adjacent digits. It is one of the most common congenital hand malformations, with an occurrence of 1 in 2,000 to 2,500 births, although the true incidence is unknown as many partial syndactylies never come to medical attention.

Syndactyly is commonly an isolated abnormality. It may be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, associated with toe syndactyly, less commonly polydactyly, or as part of a syndromic presentation. Syndromes associated with syndactyly are numerous and include Apert’s syndrome, Timothy syndrome, and Poland’s syndrome. Their identification is important due to associated diagnoses including arrhythmias with rare Timothy’s syndrome and increased complexity of reconstruction with central polysyndactyly.

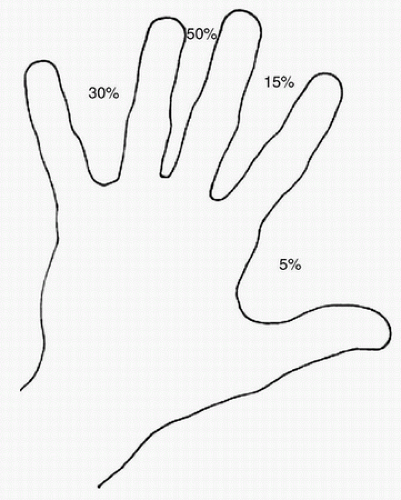

Amniotic band disruption sequence may present with syndactyly. However, this is not a primary failure of the digits to separate as in all other forms of syndactyly. Amniotic band disruption sequence is an initial normal separation of digital rays that secondarily become syndactylized as part of the banding. On exam, this is evident by sinuses between digits that can be probed and often is associated with acrosyndactyly, distal amputations, and deep skin bands. Syndactyly occurs most commonly between the long and ring fingers (50%), followed by the ring-small (30%), index-long (15%), and least commonly thumb-index (5%) web spaces. Syndromic syndactyly is more likely to present involving multiple web spaces and, at times, unusual web spaces such as fourth web space in Timothy’s syndrome (Fig. 36-1).

Syndactyly is classified according to clinical and radiographic findings, by the degree of webbing (complete or incomplete), the presence of bony fusion (simple or complex), and/or other bony anomalies (complicated) (Table 36-1). The underlying skeletal and neurovascular development may only be apparent at the time of surgery, but generally, the more complex the involvement, the more likely there will be neurovascular anatomic abnormalities.

In all cases of syndactyly, the reconstruction centers around a deficit of skin. However, it is not only the skin that is affected, and each element needs to be addressed when planning and undertaking surgical care.

TABLE 36-1 Classification of Syndactyly | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

Most complete syndactylies warrant surgical release to achieve

Maximum independent digital function

Increased grasp and pinch—especially for index-thumb syndactyly

Prevention of angular deformity—particularly border syndactyly

Ring and glove wear

Contraindications for surgery include

Inadequate skeletal stability

Hypoplastic extrinsic tendons so independent function is not feasible

Insufficient vascular supply

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Develop a preoperative plan to address each aspect.

Skin

Nail and nail fold

Neurovascular bundles

Tendons and ligaments

Bony architecture

Preoperative assessment

Clinical examination

Health status of associated medical conditions

Web spaces affected—the normal web space anatomy should be appreciated. The index-middle and ring-small web are U-shaped and the middle-ring V-shaped. Each web slopes gently down at an angle of 45 degrees from the base of the proximal phalanx dorsally to the middle of the proximal phalanx volarly.

Individual digits. Assess for independent movement and skin creases. An absence of skin creases increases the likelihood of hypoplastic extrinsic tendons and deficient joint development. A digital Allen’s test may be performed on the free border of the digit or previous separated side of a digit to assess for independent digital arterial supply.

Radiographs of the affected hand/s should be obtained preoperatively and assist with classification and anticipating surgical needs.

Review of prior operative reports to assess for vascular anomalies or ligations that may have been performed.

Considerations for the timing of surgery include, but are not limited to: influence of one conjoined digit on another, associated clinical conditions and general health status. Generally, surgery for these congenital differences is rarely performed before age 6 months because of digital size and anesthetic considerations. However, digital separation may be delayed until school age or beyond, depending on individual patient circumstances.

Anesthesia becomes safer with age. Although the effects of anesthesia on the developing brain are still being investigated, physiologically, the risk of anesthesia decreases after 6 months of age and, in all cases except acrosyndactyly with vascular compromise surgery, should be deferred until after this age. With growth, involution of neonatal adiposity occurs and neurovascular bundle size increases. Many surgeons defer separation of nonborder digits until 18 months of age although we frequently do surgery between 6 and 12 months of age.

Border digits have inherent differences in length and growth and influence hand function to a greater degree than central web spaces. Progressive deformity is an indication for earlier release and can be contemplated from 6 to 12 months of age or even early depending on the degree of deformity. In the very young, distal release alone to improve digital alignment can be performed with more complete reconstruction later.

Many families will request early surgical release and this can be considered by experienced surgeons but should not be the sole determinant of timing. Safety should always be the first priority.

Planning sequence of syndactyly releases.

When multiple webs are affected, then staged surgery is almost always preferable.

Operating on both sides of a digit risks compromising vascularity and is rarely appropriate. Congenital differences in vascular anatomy increases this risk.

Border digits should be prioritized due to the potential for angular deformity.

When all digits and web spaces are involved, the thumb-index and middle-ring webs are addressed first followed by index-middle and ring-small secondarily. However, if significant angular deformity exists in both first and fourth web spaces, then thumb-index and ring-small may be initially addressed together. This will result in three surgical encounters being required.

When index through small syndactylies occur, the index-middle and ring-small webs are initially addressed with staged surgery to the middle-ring web.

Determining the need for graft.

Graft is almost always required for syndactyly distal to the proximal interphalangeal joint—it is a condition of relative skin deficiency.

Partial syndactyly proximal to the proximal interphalangeal can more readily be addressed with graftless techniques.

Graftless techniques in complete syndactyly have been described. Such surgery requires digital defatting, altered flap techniques and have yet to gain widespread use in pediatric complete syndactyly reconstruction.

Selecting graft donor location: Ideally from an inconspicuous location, well matched for color and does not bear hair in the adult. Full-thickness skin grafts are almost always used because they are more durable and contract less than do split-thickness grafts.

Groin. The most traditional location and, in terms of being inconspicuous, is the most ideal. However, groin skin has more of a tendency to hyperpigment with age, especially in darkerskinned individuals, and if taken too medially, it will contain hair follicles and grow hair after puberty. Graft harvesting should be kept well lateral to the femoral artery to avoid this. Staying more central in abdominal creases can also be inconspicuous with less risk of hair bearing later.

Antecubital fossa. It is more conspicuous than groin graft but better matched for color and a skin crease harvest site minimizes the clinically apparent scarring. It also involves single operative extremity for ease of postoperative care and a smaller volume of graft can be taken than from the groin.

Wrist flexion crease. It provides the smallest volume of graft but also is well matched to color with less hyperpigmentation. Sufficient graft for one to two webs can readily be obtained. As it is adjacent to the surgical reconstruction, graft harvest and surgical closure are more difficult simultaneously. Some surgeons have concerns regarding social implications of scars across the flexor aspect of the wrist in terms of suicide implications, but keeping the incision in the wrist crease incision minimizes clinical scarring.

Donor tissue from excised parts utilized where the child has other congenital anomalies, most commonly polydactyly of the upper or lower extremity. Syndactyly release is frequently timed with other surgeries using skin harvested from parts that would be otherwise discarded.

Hyaluronic acid scaffold. A new promising technology. Only 2-year follow-up data are available.

TECHNIQUE

Syndactyly release incisions are planned so that the new web is composed of local flaps of native skin with intact vascularity as opposed to skin grafts. The incisions on the sides of the fingers were frequently in Z-plasty angulation to minimize the effects of graft and scar contraction during growth.

COMPLETE SYNDACTYLY RELEASE

The patient should be supine on the operating table. A hand table is used throughout the procedure. For small children, they may be angled on the operating table so that their upper extremity and head are supported on the hand table and the hand centered to the surgeon. A nonsterile tourniquet or sterile Esmarch bandage tourniquet may be used. The limb is prepped and draped freely. If a graft harvest site outside of the extremity is selected, this should also be prepped and draped. Be certain that the natural inguinal skin crease is marked if using groin graft so as to appropriately orient the graft to minimize scarring.

Consider placing nylon traction sutures in the digital pulps adjacent to the webs to be released to minimize tissue handing and place the hands of the assistant retracting outside of the working operative field. Skin flap marking and elevation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree