Surgical Management of Traumatic Conditions of the Elbow: Interposition Arthroplasty

Bernard F. Morrey

Matthew L. Ramsey

DEFINITION AND PATHOGENESIS

Posttraumatic conditions of the elbow represent a spectrum of disorders involving the elbow as a result of previous trauma. Treatment for posttraumatic conditions is individualized depending on the characteristics of the pathology as well as the functional demands and age of the patient.

Posttraumatic arthritis

Primary pathology involves posttraumatic degeneration of the articular surface.

Secondary pathologies can include contracture, loose bodies, heterotopic bone, and impingement and irritation from retained hardware.

Nonunion of the distal humerus

May involve all or a part of the articular surface

Frequently associated with marked fixed angular and/or rotatory deformity

Dysfunctional instability of the elbow

Special clinical situation where the fulcrum for stable elbow function is lost

Associated with considerable bone loss

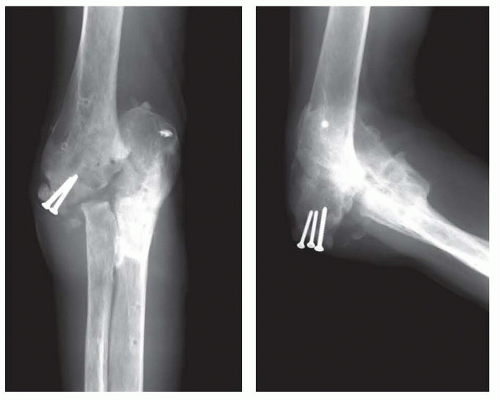

The forearm may be dissociated from the brachium (FIG 1).

Chronic instability (dislocation)

Chronic ligamentous instability of the elbow can lead to articular degeneration, particularly in the elderly osteopenic patient.

Fixed contracture and displacement are characteristic.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patient History

The patient history is directed at gaining information about the initial injury, treatments undertaken, complications of treatment, presenting complaints, and patient expectations.

Detailed investigation of the patient’s symptoms should include questions regarding the degree of pain, presence of instability or stiffness, and mechanical symptoms of catching or locking.

Presence of radiating pain especially in the ulnar nerve distribution is solicited.

Special attention is paid to night pain and pain at rest, as these suggest a possibility of sepsis. Note: A history of drainage or any evidence of infection is especially critical to elicit.

Physical Examination

Physical examination of the elbow should follow a systematic approach.

Inspection of the elbow

Especially for warmth and redness

Presence and location of previous skin incisions or persistent wounds

Alignment of the extremity at rest

Prominent hardware

Range of motion

Localization of pain during active and passive motion

Active range of motion (AROM) is assessed and compared to the opposite side. The degree of motion, smoothness of motion, and feel of the end point is established.

Normal AROM varies but should be symmetric with the opposite unaffected side.

Range of motion should be from near full extension (may have hyperextension) to 130 to 140 degrees of flexion.

Normal forearm rotation is an arc of 170 degrees, with slightly more supination than pronation.

Functional range of motion has been defined as a flexion-extension arc from 30 to 130 degrees and a pronation-supination arc from 50 degrees of pronation to 50 degrees of supination.10

Passive range of motion (PROM) is then assessed and compared to the active motion arc.

Palpation of the elbow

Should systematically review all of the bony and soft tissue structures of the elbow

The ulnar nerve needs to be carefully assessed. If previously surgically manipulated, its location should be identified if possible.

Examine for the presence of Tinel sign.

Motor function of the elbow should be assessed. In particular, the flexor (biceps and brachialis) and extensor (triceps) function should be evaluated.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain X-rays

Orthogonal views of the elbow are mandatory.

A good lateral radiograph can typically be obtained.

A useful anteroposterior (AP) radiograph can be difficult to obtain, particularly if the patient has a significant flexion contracture.

Note: If difficulty is encountered, use fluoroscopic guidance to obtain proper orientation.

Oblique radiographs can be helpful in obtaining more detail.

Advanced Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) scan

CT scans are particularly helpful in assessing the integrity of the bone and establishing whether the joint space is reasonably preserved.

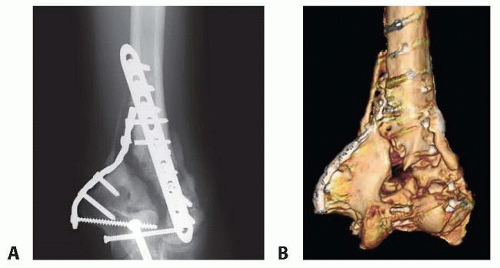

Three-dimensional reconstructions provide a better understanding of complex osseous injuries (FIG 2).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI is rarely needed in the assessment of a posttraumatic joint and is therefore used sparingly.

May be helpful to assess suspicious and atypical soft tissue deformity or swelling

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Nonunion/malunion of the distal humerus

Posttraumatic stiffness of the elbow

Chronic dislocation of the elbow

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The success of nonoperative management depends on specific features of the pathology and the motivation and goals of the patient.

Activity modification in order to reduce the forces across the elbow

FIG 2 • A. Complex injury with unclear joint pathology or state of healing. B. The 3-D reconstruction clarifies the extent of the problem.

Maintain range of motion of the elbow. Aggressive efforts to regain lost motion can inflame and thus aggravate the joint.

External bracing is occasionally used to support an unstable extremity. However, in general, bracing is poorly tolerated and functionally limiting.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical management is directed at addressing the underlying cause of disability, taking into consideration the patients age, pathology, physical requirements, and expectations.

Indications

Age and functional need prompt consideration of this intervention.

Age is a surrogate for activity.

In general, patients younger than age 55 years are always candidates for interposition—all else being equal.

Those older than age 70 years with similar pathology are usually better candidates for replacement.

Patients with pain and/or loss of range of motion who have failed nonoperative management

Posttraumatic arthritis in patients who are either too young for total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) or who are unwilling to accept the functional restrictions with TEA

The patients who do best following interposition are those with painful loss of motion when there is no requirement for aggressive, heavy use of the extremity.

Contraindications

Active or subacute infection (septic arthritis with persistent infection)8

Grossly unstable elbow

Marked angular deformity (exceeding 15 degrees)

Inadequate bone stock

Patients unable or unwilling to follow postoperative instructions

Inexperience with the technique

Pain at rest or pain without associated functional loss (relative contraindication)

Preoperative Planning

Graft options

Allograft Achilles tendon7: has the advantage of no donor site morbidity

The abundance of the tissue allows for variable thickness depending on reconstructive need.

Can also be used to reconstruct the collateral ligaments if necessary

Autogenous dermis or fascia lata

Best used for limited applications (eg capitellum)

Allograft dermal tissue

An articulated (hinged) external fixator must be available.