Surgical Management of Sacral Tumors

Xiaohui Niu

Hairong Xu

BACKGROUND

Tumors involving the sacrum mainly include primary and metastatic tumors.

Metastatic tumors are more common than primary ones.

The most common benign sacral tumor is giant cell tumor. The most common primary malignant sacral tumor is chordoma followed by chondrosarcoma.

Schwannoma, arising from the neural elements and not the sacrum, is categorized into the sacral tumors because it is clinically similar to other sacral tumors and treated the same way as well.

The symptoms, which are usually either nonspecific or similar to that of lumbar disc herniation, develop insidiously for months to years due to the potentially large presacral space. The tumors may become very huge before diagnosis.

A primary tumor often involving the sacrum is chordoma.1 Tumors in this anatomic location are of low grade and unlikely result in metastatic disease. Problem of local control may be made worse by tumor spill resulting from incomplete excision. Local spill of tumor cells with biopsy, or partial resection by an inexperienced surgeon, may severely compromise the opportunity for a complete recovery.

Surgical management of sacral tumors is challenging due to the rich blood supplies and complex anatomic structures (ie, nerves, vessels). It is frequently associated with high risk of local recurrence and complications.

Resections of the sacrum are not commonly performed.

Operation can be performed safely and deliberately through knowledge of the anatomy in this area and a full knowledge of the principles of dissection. Nerve roots and inferior border of the sacroiliac joints are both the risky locations for positive margins. In rare conditions, tumors may require en bloc resection of the rectum or annal canal plus rectum.

The perioperative complications may include massive intraoperative and postoperative bleeding; injury of rectum, bladder, etc.; wound complications; and neurologic dysfunction postoperatively.

In the recent years, the computer-assisted navigation technology has shown promise in aiding in optimal preoperative planning and in providing more precise and accurate tumor resection. Potentially, local recurrence may be reduced and neurologic function may be preserved at its best by applying this technology.

Radiation for residual may be helpful.

ANATOMY

Sacral Plexus and the Coccygeal Plexus

Lumbosacral trunk (L4, L5) courses over the sacral ala.

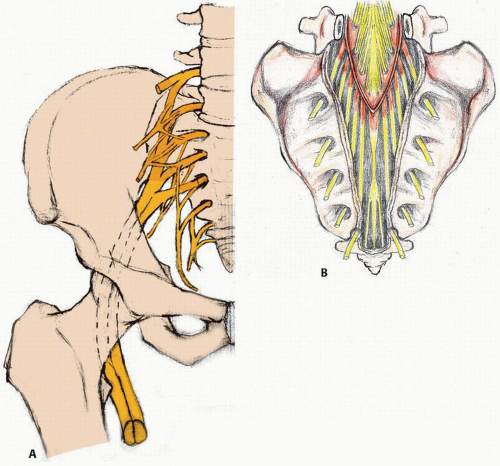

The caudal parts of the ventral branches of L4 and L5 combine to form the lumbosacral trunk (FIG 1). Together with the ventral branches of the first three sacral nerves and the upper part of the ventral branch of the fourth sacral nerve, the lumbosacral trunk forms the sacral plexus.

S1-S3 roots issue through the upper three anterior sacral foramina, the lumbosacral trunk is joined by S1 at the level of the sacroiliac joint, and S1-S5 exits the foramina sacralia pelvina.

The tip of the sacral plexus comes toward the greater sciatic foramen, lying in front of the sacrum and piriformis.

The coccygeal plexus arises from the lower part of the ventral branches of the fourth and fifth sacral nerves as well as the coccygeal nerves.

The sacral plexus provides motor and sensory nerves for the pelvic, buttocks, perineal region, the posterior thigh, most of the lower leg, the entire foot, and part of the hip joint. Except many short muscle branches for piriformis, musculus obturator internus, and quadratus femoris, the sacral plexus and the coccygeal plexus divide into the following branches.

The superior gluteal nerve (L4-L5, S1). The superior gluteal nerve, along with the superior gluteal artery and vein, departs from the pelvis via the suprapiriformis foramen. The nerve supplies the tensor fasciae latae, the gluteus minimus, and the gluteus medius muscles.

The inferior gluteal nerve (L5, S1-S2). The inferior gluteal nerve, along with the inferior gluteal artery and vein, departs from the pelvis via the infrapiriformis foramen. The nerve supplies the gluteus maximus.

The pudendal plexus. The pudendal plexus is formed by S3-S4 and portions of anterior division of S1-S2. Deep of the origin of the gluteus maximus muscle from the sacral edge, the pudendal nerve must be spared because it courses posterior to the ischial spine and then on the surface of the obturator internus in the ischiorectal fossa. It is in anterior inferior of the sacral plexus but not sharply marked off from it. It gives off the following branches. The muscular branches are derived from the fourth sacral and supply the levator ani, coccygeus, and sphincter ani externus. The visceral branches arise from the third and fourth, and sometimes from the second, sacral nerves and are distributed to the bladder and rectum and, in the female, to the vagina; they communicate with the pelvic plexuses of the sympathetic nervous system. The perineal nerve, the inferior and larger of the two terminal branches of the pudendal nerve, is situated below the internal pudendal artery. Some of the nerve fibers are distributed to the skin of the scrotum and communicate with the perineal branch of the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve. These nerves supply the labium majus in the female. The perineal nerve gives off from the nerve to the bulbocavernosus, pierces this muscle, and supplies the corpus cavernosum urethrae, ending in the

mucous membrane of the urethra. The dorsal nerve of the penis is the deepest division of the pudendal nerve. It gives a branch to the corpus cavernosum penis and passes forward, in company with the dorsal artery of the penis, between the layers of the suspensory ligament, on to the dorsum of the penis, and ends on the glans penis. In the female, this nerve is very small and supplies the clitoris. The fifth sacral nerve receives a communicating filament from the fourth and unites with the coccygeal nerve to form the coccygeal plexus. From this plexus, the anococcygeal nerves take origin; they consist of a few fine filaments that pierce the sacrotuberous ligament to supply the skin in the region of the coccyx.

The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve (S1-S3). It leaves the pelvis through the suprapiriformis foramen. It accompanies the inferior gluteal artery to the gluteus maximus and supplies the skin of the back thigh and the popliteal fossa.

The sciatic nerve (L4-L5, S1-S3). It is the longest and widest single nerve in the human body. The relationship between the piriformis muscle and the sciatic nerve is close and may be changing. In most instances, the sciatic nerve exits the pelvis via the suprapiriformis foramen. It then lies posterior (superficial) to the short external rotators (superior gemellus, inferior gemellus, and obturator internus). It then runs down the buttocks and the back of the thigh, giving rise to motor branches for the hamstring muscles. When the sciatic nerve reaches the apex of the popliteal fossa, it terminates by bifurcating into the tibial and common fibular nerves.

The dural sac ends at the S2-S3 junction. When dural sac is injured, cerebrospinal fluid leak will occur.

Radical resection of the entire sacrum would result, in addition to sphincteric incontinence, in considerable denervation of both lower extremities in the distribution of the sciatic nerves. Resections below the body of S3 vertebra do not endanger continence of the anal and bladder functions.

Vascular Anatomy

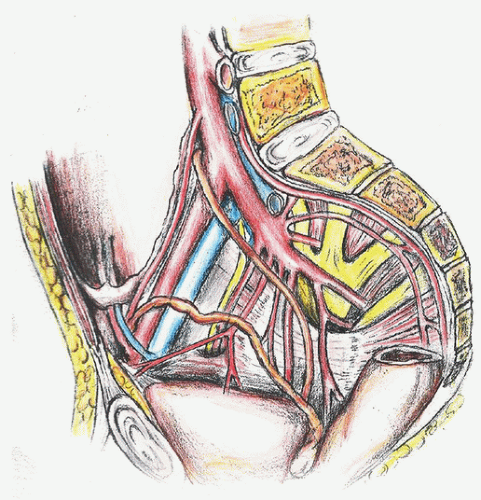

The blood supplies of sacral tumors mainly include internal iliac artery, internal pudendal artery, the superior gluteal artery, the inferior gluteal artery, the vesical artery, the rectal artery, the iliolumbar artery, and the lateral sacral artery (FIG 2).

The pertinent blood supplies of sacral tumors, which might be dealt with during operation, mainly include the superior gluteal artery, the lateral sacral artery, and the median sacral artery. There are communications among the superior gluteal artery, the subcostal artery, and the intercostal artery from the abdominal aorta. The superior and inferior arteries also have anastomosis with the femoral profound artery from the lateral iliac artery. There are anastomosis between lateral sacral artery and median sacral artery as well.

Venous anatomy generally parallels arterial anatomy but is subject to a high degree of variability and could develop proliferation and enlargement due to the tumors.

Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Sacroiliac Joint

The sacroiliac joint is a synovial structure formed between the articular surfaces of the sacrum and ilium. The articular

surface of the sacrum that conjoins with ilium is ear-shaped with complementary irregularities between the articular surfaces, which offer mechanical stability to the joint. The interosseous, anterior, and posterior sacroiliac ligaments are the strongest in this region and function to strengthen the joint.

When the transverse partial sacrectomy is performed just cephalad to the S1 neural foramina and the average resection of the sacroiliac joint is 25%, the bearing capacity of the joint reduces to 35% of the normal. When the transverse partial sacrectomy is performed just caudal to the S1 neural foramina and the average resection of the joint is 16%, the bearing capacity of the joint reduces to 72% of the normal.3

Reconstruction is not needed when performing the transverse partial sacrectomy caudal to the S1 neural foramina. Reconstruction should be considered when performing the transverse partial sacrectomy above the S1 nerve root.

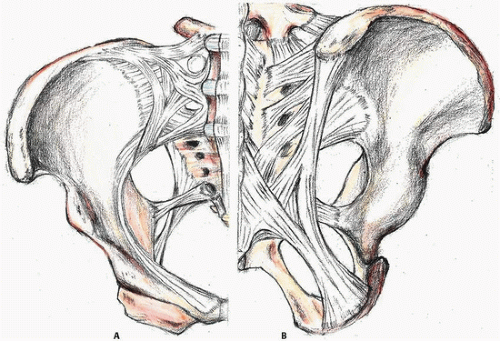

Muscles and Ligaments

The gluteus maximus originates from the posterior aspect of dorsal ilium, posterior superior iliac crest, posterior inferior aspect of sacrum and coccyx, and the sacrotuberous ligament. As it passes from the sacrum to the femur, the gluteus maximus covers the sacroiliac joint and the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments as well as a portion of the ischiorectal fossa. It inserts primarily in fascia lata at the iliotibial band and also into the gluteal tuberosity on posterior femoral surface. The arterial supplies are inferior and superior gluteal arteries and the first perforating branch of the profunda femoris artery.

The piriformis is also a very important structure for sacral tumor resection. It originates from the anterior part of the sacrum, the part of the spine in the gluteal region, and from the superior margin of the greater sciatic notch. It exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen to insert on the greater trochanter of the femur.

The erector spinae muscle arises from the anterior surface of a broad and thick tendon, which is attached to the medial crest of the sacrum, to the spinous processes of the lumbar, and the supraspinous ligament, to the back part of the inner lip of the iliac crests and to the lateral crests of the sacrum, where it blends with the sacrotuberous and posterior sacroiliac ligaments. Some of its fibers are continuous with the fibers of origin of the gluteus maximus.

The sacrotuberous ligament is situated at the lower and back part of the pelvis (FIG 3). It runs from the sacrum (the lower transverse sacral tubercles, the inferior margins sacrum, and the upper coccyx) to the tuberosity of the ischium. The sacrospinous ligament is a narrow ligament attached to the ischial spine and the lateral region sacrum and coccyx. Together with the sacrotuberous ligament, it converts the greater sciatic notch into the greater sciatic foramen and the lesser sciatic notch into the lesser sciatic foramen.

INDICATIONS

Surgical indications for primary benign/intermediate tumors such as giant cell tumor of bone, schwannoma, etc. Tumor resection, curettage, or a mixture is recommended. Intralesional margin is acceptable.

Surgical indications for primary malignant tumors such as chordoma, chondrosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma, etc. Tumor resection is required with wide or marginal margin.

Surgical indications for metastatic tumors. Surgical treatments should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Resection, curettage, and ablation are options.

Surgical indications for adjacent soft tissue sarcomas involving the sacrum. It is recommended that the tumor and the involved sacrum should be resected en bloc.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Chronic, dull, lower back or coccygeal pain due to chronic nerve compression is one of the most common presenting symptoms. It could be misdiagnosed as lumbar disc herniation. Some patients are diagnosed incidentally with benign tumors, although asymptomatic.

The typical symptom of sacrum tumors is chronic lower back pain with an alteration of bowel or urinary habits due to its mass effect and compression. Ambulation dysfunction and bowel and bladder incontinence may rarely happen.

Lower sacral tumors can grow large enough for their anterior portion to be palpated during a rectal examination.

Some large sacral tumors such as chordoma and chondrosarcoma present large bumps in the buttock.

Those patients with high-grade malignant tumors may suffer severe pain for weeks or months with difficulty in ambulation. Patients usually have to stay in one fixed position to alleviate the pain. The mass is frequently small even if it is palpable during a rectal examination.

IMAGING AND OTHER STAGING STUDIES

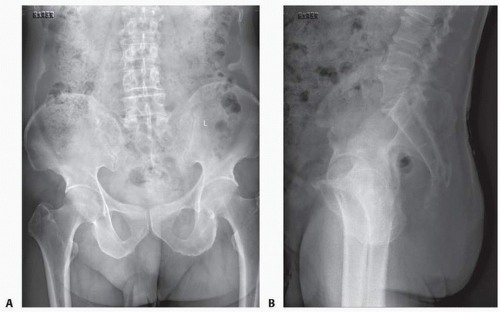

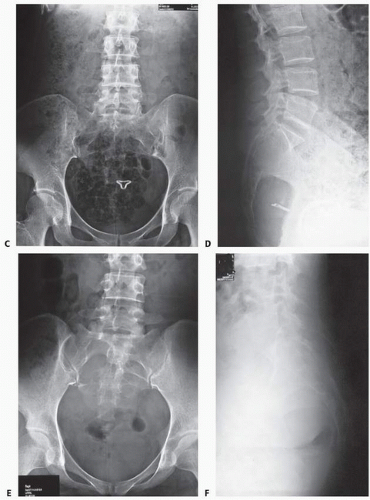

Plain Radiography

Images are often obscure and confusing especially during the early days of the disease. It is hard to arrive at a definite diagnosis with only the plain radiography in most instances.

Chordoma usually locates in the lower part of the sacrum and may be diagnosed with plain radiography in the early

days. Lesions of giant cell tumor, simple bone cyst, and aneurysmal bone cyst, usually large and totally lytic, locate in the upper part of the sacrum and may also be diagnosed with plain radiography.

Schwannoma in the sacrum almost exclusively originates from the anterior division of the sacral nerve. The enlarged anterior sacral foramina could be easily identified through plain radiography.

One should be aware that the diagnosis could be missed or delayed if only the plain radiography is taken.

However, plain radiography is necessary with the value of overview on the tumor, correlations with other images, and postoperative follow-up (FIG 4).

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast is the optimal technique for assessing the extent of bone involvement and destruction, possible ossification or calcification of the

matrix, the anatomic location, the blood supply, and the relation between the tumor and the visceral organs (FIG 5). It is helpful in differential diagnosis of benign and malignant tumors.

Chest CT is essential for staging purposes in evaluation for pulmonary metastases of malignant tumors.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast is critical for imaging soft tissue mass involvement and the relation between the tumor and the surrounding tissues (ie, vessels, nerves, muscles, visceral organs). MRI is the optimal modality for imaging soft tissue due to its superior discrimination ability than CT.

MRI with contrast may be helpful for the serial assessments of neoadjuvant therapy.

Bone Scan

Bone scan may sometimes detect small sacral lesions, which are not clearly identified by other radiographs.

Bone scan is usually used to rule out systemic disease (ie, metastasis)

Angiography

Angiography is necessary for malignant sacral tumors.

It is essential to clearly determine the blood supplies of the tumor and the pertinent vascular anatomy with angiography for evaluation of the risk of surgical management.

Selective embolization of the tumor blood supplies before surgery is significant in minimizing blood loss during surgery (FIG 6). It has taken the place of ligation and temporary block of arteries in our institution. However, it should be recognized that excessive and large areas of embolization may increase the risks of flap complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree