Surgical Dislocation of the Hip for Fractures of the Femoral Head

Milan K. Sen

David L. Helfet

INTRODUCTION

Fractures of the femoral head are commonly seen in association with traumatic dislocation of the hip (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). Hip dislocations are usually high-energy injuries and are posterior in 82% to 94% of cases (3,7,8). Classically, they are the result of a dashboard injury, with an axial load transmitted through the flexed hip (5,8, 9 and 10). The reported incidence of femoral head fractures in patients with posterior dislocations of the hip ranges from 7% to 16% (1,4,10,11). Anterior hip dislocations are less common but can also be associated with femoral head fractures, ranging from 15% (12) up to 77% in one series (3). These injuries are treated with emergent reduction of the femoral head to decrease the risk of avascular necrosis secondary to ischemia caused by tension on the blood supply of the femoral head (13, 14, 15 and 16). This is preferably done within 6 to 12 hours from the time of injury (4,13,17). Prior to attempting a closed reduction, it is important to exclude the presence of a concomitant femoral neck fracture. Postreduction, an axial CT scan with 2-mm cuts is necessary to ensure a concentric reduction that is free of intraarticular fragments (5,18,19). If a displaced femoral head fragment is identified on the plain radiographs or CT scan, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is usually required (4). At the same time, the surgeon can address other associated musculoskeletal injuries, commonly fractures of the acetabulum, and femoral neck and shaft (4).

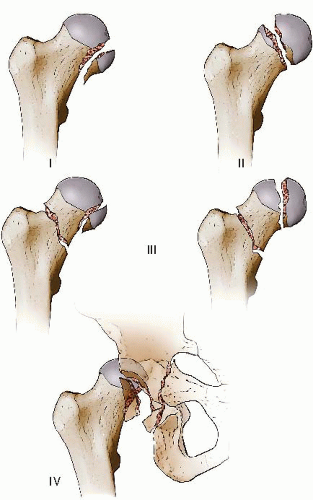

The Pipkin classification was introduced in 1957 and includes four femoral head fracture subtypes. A Pipkin type I fracture occurs below the ligamentum teres. The Pipkin type II fracture propagates above the ligamentum teres. In the Pipkin type III fracture, the fracture is similar to a type I or II but is associated with a femoral neck fracture. And the Pipkin type IV fracture is similar to a type I or II but with an associated acetabular fracture (Fig. 44.1).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

As these injuries are often seen in the setting of high-energy trauma, it is important that the patient is evaluated appropriately for associated abdominal, thoracic, and craniofacial injuries (8). In the presence of a femoral neck fracture, postreduction hip joint asymmetry, progressive sciatic nerve injury, or an intra-articular fragment displaced at least 2 mm or rendered the hip unstable, urgent open reduction and fixation of the fragments is warranted (1,20, 21 and 22). For Pipkin type I or II femoral head fractures, free or nonreduced fragments that remain after reduction must be excised or reduced and stabilized to avoid early posttraumatic arthrosis (5,11,14,17). Historically, recommendations have included excision of large fragments, up to one-third of the femoral head (2,4,5,21). However, because the entire acetabulum is involved in weight bearing (23), any fragment that is

amenable to fixation should be rigidly fixed. Smaller fragments may be excised (6,14,22,24, 25, 26, 27 and 28). Small avulsion fractures of the ligamentum teres can be treated nonoperatively.

amenable to fixation should be rigidly fixed. Smaller fragments may be excised (6,14,22,24, 25, 26, 27 and 28). Small avulsion fractures of the ligamentum teres can be treated nonoperatively.

In the past, much controversy existed in regards to the optimal surgical approach for fixation of femoral head fractures. Initially, the Kocher-Langenbeck approach was used. It has the advantage of addressing fractures of the posterior acetabular wall, but allowed only limited access to the articular surface of the femoral head for fracture reduction and fixation. In addition, some studies identified an increased incidence of avascular necrosis of the femoral head using this approach as compared to the Smith-Peterson approach (26,27). Alternatively, the Smith-Petersen approach had the advantage of providing access to the anterior portion of the femoral head and allowed for débridement of intra-articular debris. However, it did not allow complete visualization of the femoral head, and it did not allow the surgeon to address posterior acetabular wall fractures. In addition, heterotopic ossification has been shown to be a significant risk with the anterior approach (24,27). While combined anterior and posterior approaches would improve visualization in the case of extensive femoral head fractures, there is an increased risk of complication associated with such extensive dissection.

In 2001, Ganz et al. (29) described a technique for surgical dislocation of the hip. It involves a Kocher-Langenbeck approach with a trochanteric osteotomy and anterior dislocation of the hip. The advantage of this approach is that it allows visualization of the entire femoral head as well as the full circumference of the acetabulum. Using this exposure, the surgeon can obtain anatomic reduction and rigid fixation of the femoral head fragments, and a thorough débridement of the joint, without compromising the blood supply to the femoral head (29, 30, 31, 32, 33 and 34).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree