Surgical Dislocation of the Hip

Farshad Adib

Young-Jo Kim

DEFINITION

Surgical dislocation of the hip can be done safely to treat a number of conditions, including femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), labral tears, chondral injuries, reduction of femoral neck fractures, femoral head, acetabular fractures, excision of tumors, reduction of acute severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), or any condition that requires wide complete access to the hip joint.14, 15

There is little morbidity associated with this procedure, and avascular necrosis of the femoral head is a rare complication.5

This technique allows functional assessment of motion intraoperatively which is the most critical step in the treatment of FAI. Majority of reoperations after FAI treatment is due to under- or overcorrection.4

Also, surgical hip dislocation approach is comprehensive enough to assess and treat extra-articular impingement at the same time.16

ANATOMY

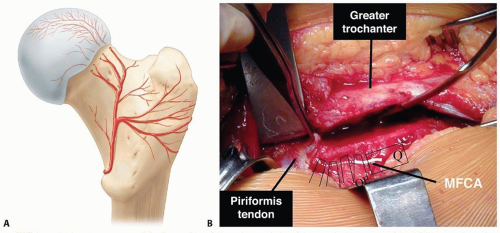

The blood supply to the femoral head is mainly from the medial femoral circumflex artery (MFCA) (FIG 1A).17

The intact external rotator muscles, most notably the obturator externus muscle, protect the MFCA during the dislocation (FIG 1B).7

PATHOGENESIS

In FAI, anatomic deformity leads to abnormal contact between the proximal femur and the acetabular rim at the terminal extent of motion. This repetitive collision damages the soft tissue structures within the joint.3

In cam impingement, an abnormal prominence on the femoral neck passes into the hip beneath the labrum and mechanically damages the labrum and cartilage of the acetabulum.

Pincer impingement occurs with overcoverage of the acetabular rim impinging on the anterior femoral neck or head-neck junction with terminal flexion.

Both cam and pincer impingement can, and frequently do, coexist.

The early chondral and labral lesions that occur in physically active adolescents and young adults can progress and result in degenerative joint disease of the hip.

Causes of FAI can be idiopathic, secondary to an SCFE, anterior overcoverage of the hip with a retroverted acetabulum, residual deformity from Perthes disease, or posttraumatic changes.

NATURAL HISTORY

A pistol grip deformity of the femoral head has been associated with early arthrosis of the hip.9

End-stage osteoarthrosis of the hip, once thought to be mainly idiopathic, is now believed to be a result of mild deformities similar to those caused by childhood diseases of the hip such as developmental hip dysplasia, SCFE, and Legg-Calvé-Perthes.1

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

FAI usually presents in active adolescents or young adults with slow onset groin pain, which may be exacerbated by athletic activities.

Many patients have difficulty sitting for long periods and adjust their seating posture to decrease lumbar lordosis to allow less flexion at the hips. Frequently, they complain of difficulty getting into or out of a car.

There can be a family history of hip pain, early arthrosis, or hip arthroplasty.

Patients may walk with an antalgic gait, favoring the side of impingement. A foot progression angle externally rotated may indicate a chronic SCFE or femoral retroversion.

The impingement test, if positive, shows reproducible groin pain with internal rotation, which is relieved with external rotation.

The physical examination should include both flexion and internal rotation range-of-motion tests.

Patients with impingement will have less than 90 degrees of true hip flexion.

Patients with impingement will have less internal rotation in flexion than extension and may have a compensatory external rotation of the hip as it is flexed.

Radiographic findings of FAI are common in the normal, healthy population; therefore, it is paramount that good clinical-radiographic correlation be done. Additionally, other causes of hip pain such as osteoid osteoma, stress fracture, osteonecrosis are ruled out.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

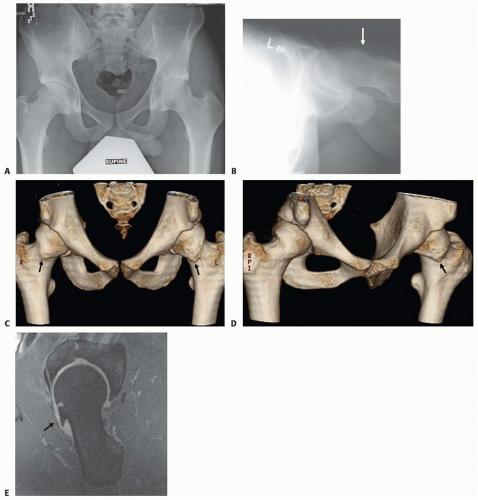

Plain radiographs should include an anteroposterior (AP) view of the pelvis and a lateral view of the hip (FIG 2A,B).

The maximal deformity of the head-neck junction in FAI could be localized best by the 45-degree Dunn view.10

Computed tomography (CT) scans with two- and three-dimensional (3-D) reconstructions are helpful for preoperative planning and detecting subtle femoral head-neck junction prominence (FIG 2C,D).

Magnetic resonance imaging can further delineate the labral and cartilage pathology (FIG 2E). If the study is performed with gadolinium and high-resolution sagittal oblique or radial sequences, labral pathology can be detected.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

FAI

Labral tear

Hip dysplasia

SCFE

Acetabular retroversion

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management includes cessation of aggravating activities and symptomatic treatment using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories.

Physical therapy to strengthen the hip musculature does not address the mechanical impingement of FAI but may have a role in affecting pelvic inclination.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Hip pathology may be addressed through hip arthroscopy. However, it may be difficult to dynamically assess hip mechanics before and after débridement.

Femoral head-neck osteoplasty may be performed through an anterior approach to the hip without a surgical dislocation. However, the articular cartilage of the acetabulum and most of the femoral head cannot be evaluated with this limited approach.

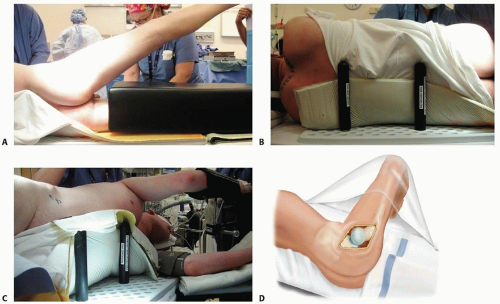

Preoperative Planning

All imaging studies are reviewed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree