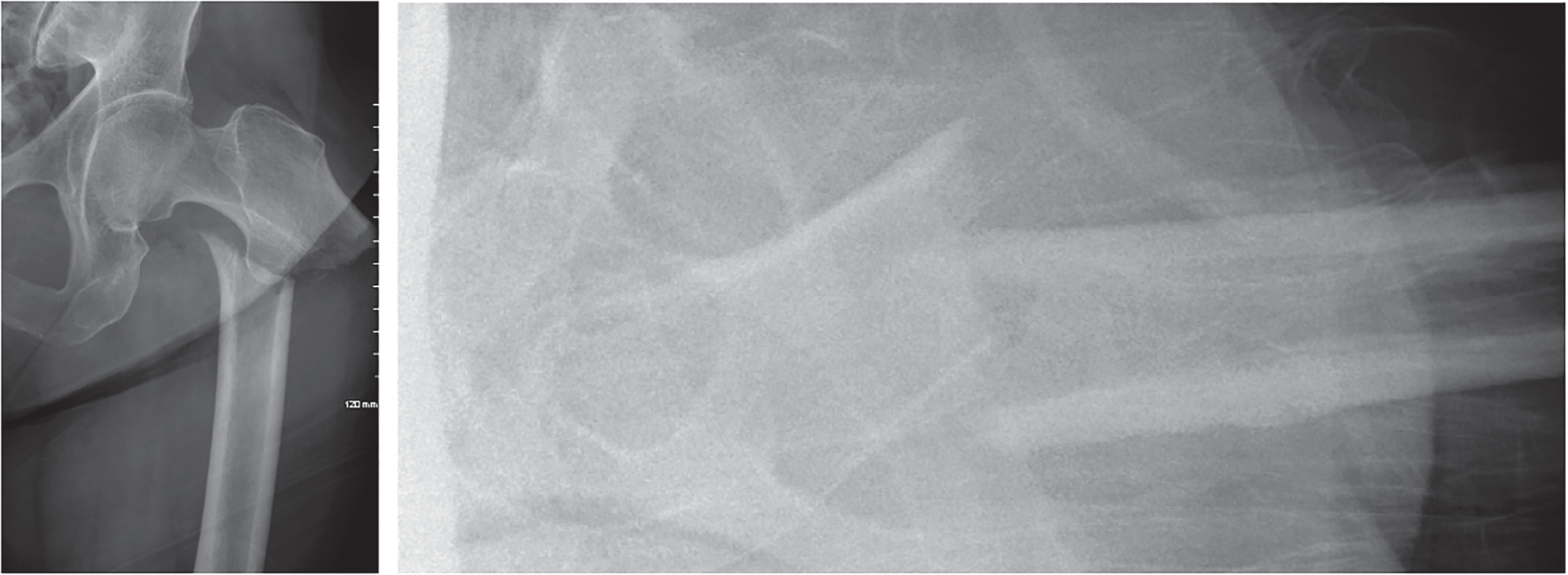

John Morellato BSc (Pharm) MBBS (Hons) FRCSC1, Steven Papp BSc MSc MD FRCSC2, Wade Gofton BSc MSc MD FRCSC2, and Allan Liew BSc MD FRCSC2 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA 2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Ottawa Civic Hospital, Ottawa, ON, Canada When performing intramedullary nailing of subtrochanteric fractures, there has been debate over different aspects of the surgical technique including the starting point. The insertion site for anterograde nailing of subtrochanteric femur fractures can be located in the piriformis fossa or the tip of the trochanter. It should be noted that the term piriformis fossa is actually a misnomer and anatomically incorrect, although this has been propagated as the start point for femoral nailing in the literature for decades.1,2 The correct name is the trochanteric fossa, but to keep the nomenclature consistent with North American literature we have chosen to keep with the term piriformis fossa. A piriformis fossa starting point offers colinear access to the shaft for reaming and nail insertion of a straight nail and possible decreased risk of varus malalignment. Fracture reduction is important when dealing with a subtrochanteric femur fracture; however, this insertion site may involve more soft tissue compromise than a start point at the tip of the trochanter.3,4 A start point at the tip of the trochanter may be technically easier to obtain; however, anatomic variability in the start point and varying proximal nail geometry may add complexity when choosing this start point. One study observed that the tip was ideal as a start point in only a minority of cases, and recommended preoperative templating of the contralateral intact femur to identify the appropriate start point to prevent malreduction of the fracture.5,6 Figure 98.1 AP and lateral x‐ray of a proximal femur fracture. This is an OTA 31A3.1 type femur fracture with typical noted deformity. There is one prospective randomized trial (level I), one prospective cohort study (level II), and one retrospective cohort study (level III) that specifically addresses this question. The only randomized study to date included 34 patients who were randomized to one of two implants that had a piriformis start or a trochanteric start respectively (level I).7 This study was powered to detect a significant difference (200 mL) in blood loss and there was no difference between the two groups in this regard. With respect to varus malalignment, this study showed 2 of 17 patients in the piriformis fossa group and 4 of 17 patients in the trochanteric group had varus malalignment on follow‐up x‐rays. This was not statistically significant; however, this study was underpowered for this outcome. Several other outcomes were compared, including duration of surgery, union rate, complication rate, and functional outcomes, and there were no differences between the two groups for these outcomes in this small patient sample. The other prospective study was a multicenter cohort study that included 108 patients treated with a single implant that differed only in proximal lateral bend which was used either through a piriformis or trochanteric entry.8 This study showed that piriformis entry nails had a mean 12‐minute longer operative time – 75 minutes (range 31–131) versus 62 min (range 14–193), (p = 0.08) – and a 61% increase in fluoroscopic time – 153 seconds (range 16–662) versus 95 seconds (range 20–375). These differences were amplified in obese patients where operative time was 30% longer and fluoroscopy time was 73% higher. There were no varus malreductions in either group and only one patient in each group needed further intervention (exchange nailing) for nonunion. Functional outcomes were recorded using the lower‐extremity measure which showed no difference between the groups at any time point (4, 6, and 12 months). It should be noted that the authors used a modified greater trochanteric (GT) start point (either slightly medial or lateral to the tip of the GT) that was individualized for each patient, taking into account the anatomy of the patient’s proximal femur as well as the geometry of the nail. This idea of a variable trochanteric start point is supported in other anatomic and radiographic studies, and it is accepted that a correct trochanteric entry point is slightly medial to the tip of the greater trochanter in the anteroposterior (AP) view and slightly posterior in line with the shaft on the lateral view (due to the anterior offset of the GT).5,6,9,10 There is one retrospective cohort study that compared the two starting points with respect to nerve and muscle function postoperatively with outcomes out to a mean of 22 months.11 This study included only 17 patients (9 in the piriformis group and 8 in the trochanteric entry group). They looked at whether the patients had a Trendelenburg gait, electromyographic (EMG) changes in their hip musculature, differences in their Harris Hip Score and Visual Analog Scale (VAS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) changes of the soft tissues, and differences in muscular endurance around the hip. Overall, five patients in the piriformis group had a Trendelenburg gait and four had EMG evidence of injury to the superior gluteal nerve which had since recovered. The piriformis group had decreased endurance on the isokinetic testing of the hip range of motion; however, the clinical relevance is unknown. Overall, this was a very small retrospective study with fragile results and the clinical relevance is questionable, although it does fuel the need for larger studies.

98

Subtrochanteric Femur Fractures

Clinical scenario

Top three questions

Question 1: In patients with subtrochanteric femur fractures treated with an intramedullary nail (IMN), does a trochanteric start point provide superior outcomes to a piriformis fossa start point?

Rationale

Clinical comment

Available literature and quality of the evidence

Findings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree