CHAPTER 38 Subscapularis deficiency after shoulder instability procedures—prevention and management

Prevention of subscapularis failure during subscapularis detachment, mobilization, and repair provides the optimal clinical outcome.

Prevention of subscapularis failure during subscapularis detachment, mobilization, and repair provides the optimal clinical outcome. Recognition of subscapularis failure or loss of function after surgery allows for prompt repair before development of tendon retraction, atrophy, and adhesions.

Recognition of subscapularis failure or loss of function after surgery allows for prompt repair before development of tendon retraction, atrophy, and adhesions. Reconstructive options with soft tissue augmentation and/or pectoralis major transfer are available when the subscapularis is irreparable.

Reconstructive options with soft tissue augmentation and/or pectoralis major transfer are available when the subscapularis is irreparable.Introduction

Subscapularis dysfunction following open anterior stabilization of the shoulder is a challenging dilemma for the surgeon. Failure to recognize loss of subscapularis integrity may lead to postoperative pain, loss of function, recurrent instability, and internal rotation weakness.1–4 Multiple approaches to addressing the subscapularis during surgery have been described, and focus should be placed on a secure repair to allow tendon healing.4 Studies have shown that takedown of the subscapularis may impair the integrity of tendon healing and causes atrophy or fatty infiltration of the muscle.3–7 When failure does occur, knowledge of anatomy and reconstructive options provides the best opportunity to decrease recurrent instability and provide a good clinical outcome. A carefully monitored postoperative rehabilitation protocol is important to protect the repair.

Preoperative history, examination, and radiographic findings

History

When evaluating a patient with persistent symptoms following an open, anterior stabilization procedure, it is important to obtain a thorough history and have a high degree of suspicion for subscapularis insufficiency. Information that is useful in making treatment decisions follows: the patient’s original presenting symptoms, the surgical procedure performed along with the operative notes from the treating physician, any perioperative complications such as infection or trauma, whether or not the original presenting symptoms resolved after the surgery, and the character of the current symptoms. It is important to determine if the patient’s current symptoms are the result of a traumatic event, or if they have been persistent following the previous surgery. Patients with subscapularis deficiency may complain of recurrent instability, persistent pain that may or may not localize to the anterior portion of the shoulder, or weakness with internal rotation.2,3,6,7 As with any postoperative patient, the physician should ask about symptoms consistent with infection such as fever, chills, night sweats, and swelling or drainage from the operative site. However, it is important to remember that an infection with an indolent organism, such as Proprionobacterium acnes, can still be present even in the absence of such symptoms.

Physical examination

Patients with complete subscapularis ruptures often have increased passive external rotation compared with the contralateral side (Fig. 38-1). This is usually associated with weakness in internal rotation. However, weakness may not always be present because other internal rotators such as the pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, and the teres major may be able to compensate for the torn subscapularis.2,4,8,9

(From Lyons RP et al: Subscapularis tendon tears. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 13(5):353–363, 2005, Fig. 2, p 356.)

Isolated subscapularis weakness can be detected with various examination techniques.2,4,8,9 The belly press test is performed by having the patient press their palm against their belly with their wrist in neutral position and the elbow anterior to the chest. The test is positive if the patient has to flex their wrist and their elbow falls back. The belly press test has been shown to isolate the upper subscapularis more than the lower subscapularis. The lift-off test is performed by having the patient place their hand behind their back at the level of the lumbar spine. They are then asked to lift their hand away from their back. In a positive test, the patient cannot lift or hold their hand away from the back. The lift-off test is only accurate if the patient has full range of internal rotation and is able to hold the provocative position without pain.

Radiographic findings

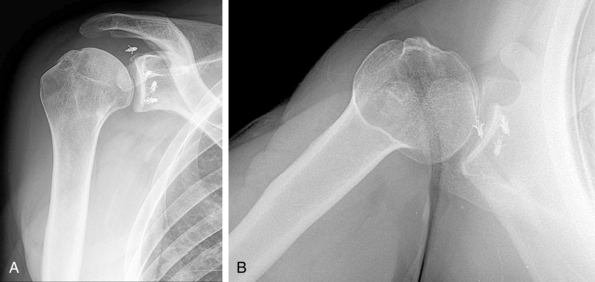

Radiographs should be obtained during the initial visit and should consist of an anteroposterior, axillary lateral, and an outlet view. In cases of instability, the Stryker notch view is useful in identifying the presence and extent of a Hill-Sachs lesion, and the West Point view determines bone loss on the anterior glenoid. In the setting of isolated subscapularis rupture, radiographs usually are normal (Fig. 38-2). However, they should be carefully examined for the position of any hardware that was placed during previous surgeries and subluxation of the humeral head anterior to the glenoid on the axillary view. The presence of osteophytes on the anteroposterior view and joint space narrowing on the axillary view provide information as to the amount of arthritis present.

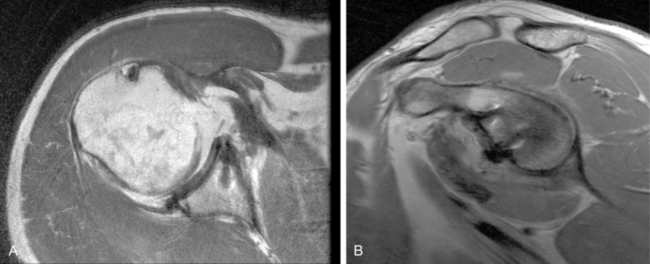

Imaging specific to the soft tissue is usually necessary to confirm the diagnosis and aid in surgical planning. Ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) have all been described in evaluation of the subscapularis. These studies evaluate the integrity of the subscapularis tendon insertion into the lesser tuberosity. This is best evaluated on the axial images (Fig. 38-3). On MRI, normal tendon is hypointense on T1 and T2 weighted images. When the tendon is torn, it appears disorganized and the signal turns hyperintense on both sequences. CT and MRA demonstrate contrast extravasation at the lesser tuberosity in the setting of a tear. The amount of fatty degeneration in the muscle belly of the subscapularis also should be determined on the sagittal oblique images medial to the glenoid. Fatty degeneration is seen in chronic tears and is predictive of poor tendon quality during surgery and impaired healing postoperatively.10 The LHBT also should be evaluated for subluxation and tears.

Description of techniques

Surgical anatomy

The subscapularis muscle is the largest and most powerful of the rotator cuff muscles contributing to internal rotation strength, humeral head depression, shoulder adduction and abduction, and active stabilization of the glenohumeral joint.2,4 It is a multipennate muscle that arises from the anterior surface of the scapula, and the upper two thirds of the tendon inserts along the lesser tuberosity.4 The lower one third inserts along the humeral metaphysis and is primarily a direct muscular attachment. The superior edge of the subscapularis contributes to the border of the rotator interval.2

The anterior circumflex artery and associated veins course laterally along the lower, muscular portion of the subscapularis. At the anterior and inferior aspect of the muscle, the axillary nerve enters the quadrangular space with the posterior humeral circumflex vessels. The subscapularis muscle is innervated primarily by the upper (C5-6) and lower (C5-C7) subscapular nerves. The upper subscapular nerve consistently originates from the posterior cord and contributes to the majority of the muscle. Variations in innervation and contributions from the axillary nerve have been described previously.2

Other important structures encountered during surgical dissection include the coracoid process and attached short head biceps, coracobrachialis, and pectoralis minor. A subcoracoid bursa exists between the coracoid and subscapularis that may be a source of adhesions during repair. The musculocutaneous nerve pierces the coracobrachialis on average 6.1 cm distal to the coracoid.11 The axillary artery and brachial plexus reside medial to the coracoid process. Finally, the axillary nerve travels medially along the anterior surface of the subscapularis muscle before entering the quadrangular space with the posterior humeral circumflex vessels.

Patient positioning

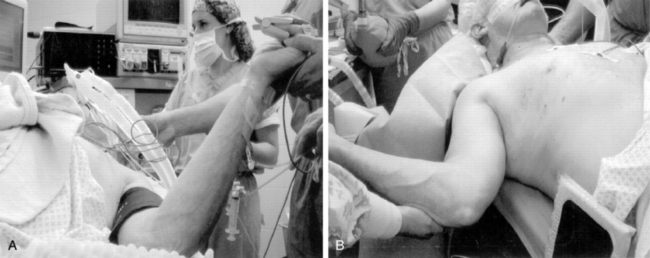

Before positioning, our institution routinely performs regional anesthesia on the affected extremity. In addition, for revision surgery and in muscular patients, general endotracheal anesthesia is used to ensure complete muscular relaxation. The patient is then placed in the beach chair position with the head of the bed elevated approximately 30 to 45 degrees. An examination under anesthesia is then performed to document range of motion, ligamentous laxity, and glenohumeral joint stability. An articulated arm holder, such as the McConnell Arm Holder (McConnell Co., Greenville, TX), also is used for positioning of the extremity. Previous authors have highlighted the necessity of appropriate retractors, implants, and assistance before the initiation of the case.12 The arm is held slightly abducted and forward flexed to relax the deltoid.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree