CHAPTER 129 Spondylolysis

INTRODUCTION

Spondylolysis is a devastating injury to a young athlete. It is the most frequent lumbar spine injury in the adolescent population. Sixty percent of all adolescent athletes experience low back pain of some sort, but only 6% are diagnosed with an acute spondylolysis.1–3 An acute spondylolysis is a stress fracture of the pars articularis or a complete breakthrough of the pars articularis. Most patients who suffer from spondylolysis have low back pain on extension, but the pain may radiate into the legs as it worsens. If the patient is placed in a lumbosacral corset, there may be immediate relief of the pain with almost complete relief of the pain within 5 days; yet if the athlete returns to the activities, the pain will return immediately. This chapter’s goal is to explore the biomechanics, diagnostic work-up, and treatment for spondylolysis.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

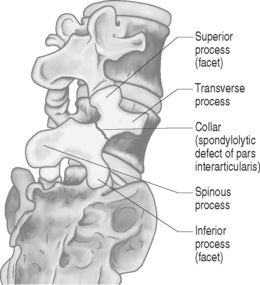

The lumbar vertebra is made up of an anterior portion, the vertebral body, and the posterior elements, which are made up of the pars as well as the facet and joints and spinous process. The lamina connects them together. When a normal person performs most activities, it is either in the standing or sitting position. The bulk of these pressures on the spine are on the vertebral body and very little is on the posterior elements, i.e. the pars and facet joints. When athletes do extension and rotation, such as winding up to pitch a baseball, back flips in gymnastics, or kicking in soccer, extra force and weight are placed on the posterior elements, which can cause one of two things to happen. The most common result is that the facet joints of the posterior elements become inflamed and develop an overuse syndrome, termed facet joint synovitis.4,5 The other result of overuse becomes a stress fracture or spondylolysis. The only way to differentiate between facet synovitis and spondylolysis is with radiographic testing, which will be described later in this chapter.6 The partes themselves are the thinnest parts of the neural arch and are the most susceptible for a fracture within the posterior elements. A recent study by Chosa et al. demonstrated this in a three-dimenstional, mechanical study of the lumbar spine.7 Their study showed that the stress in the pars intra-articularis was least with compression alone but stronger under compression with lateral bending along with rotation and extension. It was the highest with extension and rotation. Consequently, repetitive extension with rotation should be considered a relatively high-risk factor for the development of spondylolysis.8 This is no surprise to the practitioner who sees most of these injuries in the athletes who perform extension–rotation movements, such as offensive linemen in football, wind-up players in cricket, as well as pitchers in female softball and male hardball.

DIAGNOSIS

The initial diagnostic test should be a plain radiographic examination of the lumbar spine including anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views. The AP perspective can rule out scoliosis. The obliques are done to look for a ‘Scottie dog’ fracture of the neck or the pars (Fig. 129.1, 129.2A,B) A pars defect can be detected in the lateral view, but its primary benefit is to identify spondylolisthesis.9 Plain radiographs may be normal when there is only a stress reaction and not frank fatigue leading to fracture or when the spondylolysis has only recently occurred. The next step would be to perform a single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) multiplanar bone scan. If the SPECT scan and plain films are positive, the evidence suggests a stress fracture. When the plain films are negative and the SPECT scan is positive then a stress reaction is the likely diagnosis. If the SPECT scan and plain films are negative the diagnosis is probably not spondylolysis.10,11 The third test of choice for this condition is a computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 129.3). A recent study by Stretch et al. showed that the CT scan was very sensitive in showing nonunion and healing6. Using thin-slice CT, they were able to show with repeat studies of the CT scans complete healing in 8 out of 9 injured athletes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not of much benefit, even using bone windows. In a recent study Sherif and Mahfouz attempted to place the epidural space in an anterior position between the dura mater and spinous process to diagnose spondylolysis.12 This allows for different tissues to contrast with each other to brighten the bone views. Unfortunately, the MRIs were not very beneficial even with the new technique.12 Additionally an MRI might identify if there is concurrent disc disease or spinal cord pathology (Fig. 129.4). This obviously will not be observed with X-ray or SPECT scan. The CT scan may show some disc disease, but not to the same degree as MRI. If the X-ray is negative, either CT or SPECT scan can be perfomed. If negative, either CT or SPECT scan can be performed. If a bone scan is performed and is positive, the patient can be treated symptomatically. At the end of the treatment, the patient can have a CT scan.13 If the CT scan shows complete union, then no further treatment is necessary. Other testing that may be needed for adolescents with back pain are a rheumatoid work-up with CBC and sedimentation rate, HLA-B27 and C-reactive protein looking for spondylitis, which could mimic the pain of spondylolysis. If there is a question with continued symptomatology without much relief from the current treatment, diagnostic injections, under fluoroscopy, of the medial branch nerve or the pars itself would be of benefit and give enough information to identify the source of the pain. For patients needing to return to play immediately, this is definitely a treatment option for short-term activity, but not for a long-term solution.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree