Soft Tissue Management Following Traumatic Injury to the Femur

Thomas F. Higgins

Open injuries of the femur and thigh are common. The need for major soft tissue coverage in this area in the setting of trauma is uncommon due to the generous surrounding muscular envelope. Soft tissue coverage of the femur can be a concern in certain situations such as power takeoff injuries or pedestrians struck by motor vehicles; however, the majority of these defects may be covered with skin grafts, and the need for vascularized free tissue transfer is unusual. Despite this, there are several components to soft tissue management in this area which may be used during exposure to the proximal and distal portions of the femur. Simple alterations in established techniques can lead to improved postoperative contour, improved soft tissue coverage of hardware, and decreased rates of postoperative infection and stiffness following elective and emergent surgical procedures.

This chapter covers four major areas of concern with regard to soft tissue management in the thigh:

The approach to the proximal femoral shaft and intertochanteric zone

The approach for the repair of supracondylar and intra-articular distal femur fractures

Exposure for the treatment of open femur fractures

The management of post-traumatic arthrofibrosis of the knee with the use of a Judet quadricepsplasty

Approach to the Lateral Proximal Femur

Indications/Contraindications

Fractures of the proximal femur, whether femoral neck or intertrochanteric, constitute the majority of all femur fractures (9). The soft tissue management issues in this portion of the proximal femur are the relative dearth of coverage over the greater trochanter and the area of the femur just distal to the vastus lateralis. Frequently, plate and screw implants and laterally based orthopaedic constructs will be prominent and symptomatic, particularly in thin patients. An approach that maximizes soft tissue coverage over the lateral aspect of the proximal femur and restores the most normal anatomy will be described. Rather than a direct lateral approach cutting through the vastus lateralis, which has been frequently advocated for this operation, a simple modification provides a more anatomic dissection and a friendlier soft tissue reconstruction.

Patient Positioning

The patient is positioned as desired for ultimate reduction and fixation goals.

Surgery

A direct lateral approach begins 1 cm proximal to the vastus ridge and extends as far distally as necessary for osteosynthesis. On the coronal plane, the incision should be 1 cm posterior to the midcoronal point of the femur (Fig. 25-1). Dissection is taken down to the iliotibial band, and this is divided in line with its fibers (Figs. 25-2 and 25-3).

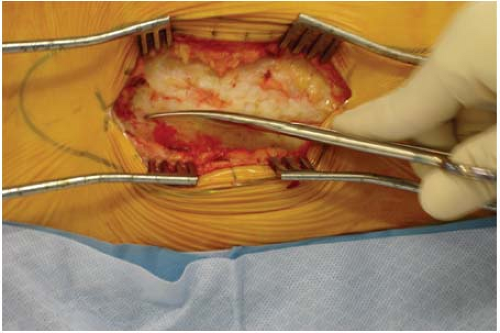

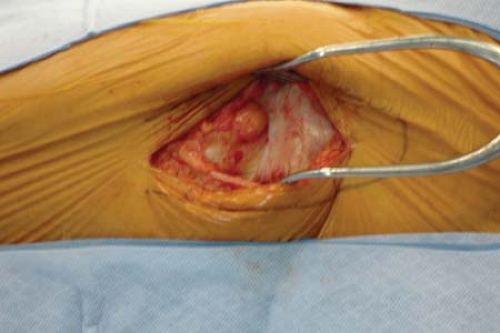

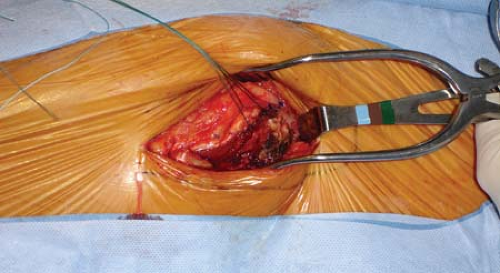

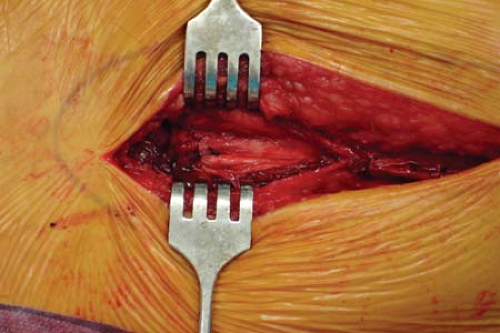

A gentle sweeping motion with a sponge will clear trochanteric bursa or areolar soft tissue that lies in this layer. Particularly fibrotic bursal tissue may need to be excised with scissors (Fig. 25-4). This will reveal quite clearly the proximal extent of the vastus lateralis and its insertion at the vastus ridge and the confluence with the distal extent of the vastus medialis tendon. Rather than directly incising the vastus lateralis in the midcoronal point of the femur, a J-shaped incision is performed. Leaving several millimeters of the vastus lateralis tendon still attached to the vastus ridge, the tendon is incised from its anterior extent posteriorly until connecting with the lateral intermuscular septum (Figs. 25-5 and 25-6). The dissection is then taken through the most posterior fibers of the vastus lateralis extending from proximal to distal, just anterior to the lateral intermuscular septum. The

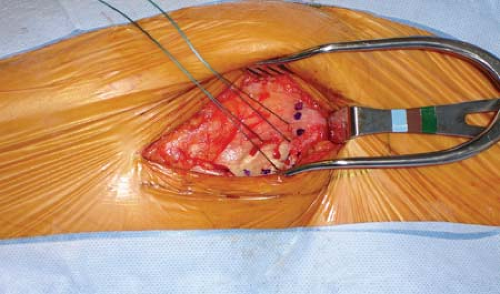

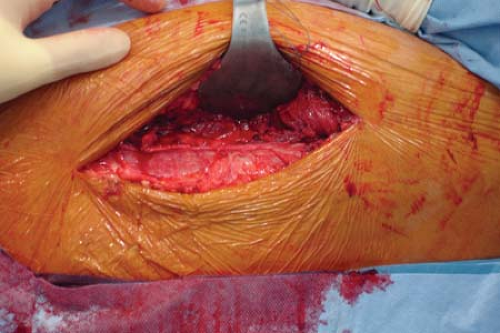

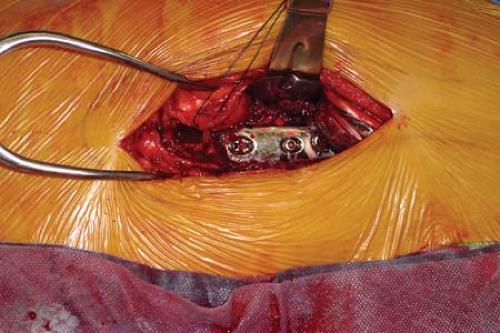

vastus tendon is tagged with a heavy braided nonabsorbable suture before being detached from the vastus ridge (see Fig. 25-5). As the dissection extends greater than 5 cm distal to the vastus ridge, the first perforating branch off the profunda femoris will be encountered penetrating the lateral intermuscular septum. These perforators should be ligated or cauterized. A gentle sweeping motion with an elevator from posterior to anterior along the proximal femur will allow reflection of the vastus lateralis in an anterior direction (Fig. 25-7). The periosteum and deepest soft tissues should not be stripped off the femur. For ideal visualization at this point, a Bennett retractor is placed anterior to the femur, and an assistant holds this forward (Fig. 25-8). Osteosynthesis proceeds as planned.

vastus tendon is tagged with a heavy braided nonabsorbable suture before being detached from the vastus ridge (see Fig. 25-5). As the dissection extends greater than 5 cm distal to the vastus ridge, the first perforating branch off the profunda femoris will be encountered penetrating the lateral intermuscular septum. These perforators should be ligated or cauterized. A gentle sweeping motion with an elevator from posterior to anterior along the proximal femur will allow reflection of the vastus lateralis in an anterior direction (Fig. 25-7). The periosteum and deepest soft tissues should not be stripped off the femur. For ideal visualization at this point, a Bennett retractor is placed anterior to the femur, and an assistant holds this forward (Fig. 25-8). Osteosynthesis proceeds as planned.

FIGURE 25-1 Incision drawn over the greater trochanter. Dotted transverse line represents the vastus ridge. |

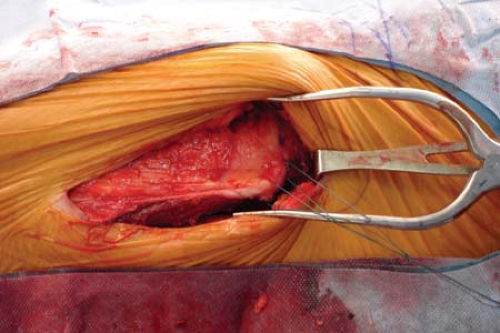

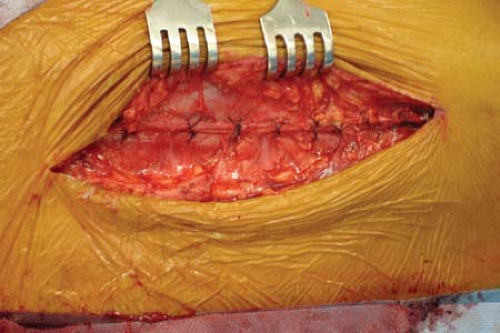

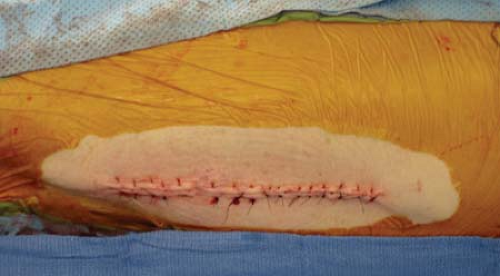

The Bennett retractors make for easy retraction and permit reduction and fixation. At the conclusion of the procedure, Bennett retractors are simply removed, and gravity allows the vastus to fall back into place, padding and directly covering the implant (Fig. 25-9). The most proximal origin of the vastus lateralis is then repaired back to its tendinous origin with a heavy braided nonabsorbable suture (Figs. 25-10 and 25-11). The posterior aspect of the vastus lateralis does not need to be repaired. The iliotibial band is repaired with interrupted nonabsorable suture, and the skin may be closed according to surgeon preference (Figs. 25-12 and 25-13).

This approach is most helpful for the placement of a dynamic hip screw, blade plate, or locking proximal femoral plate. It offers less scarring, as the muscle belly has not been interrupted. This should also be a more functional repair, as less damage presumably has been done to the vastus origin by dividing it and repairing it, rather than by directly insulting it with a midgastric approach.

Postoperative Management

In the elderly population with intertrochanteric hip fractures, patients are generally allowed to bear weight as tolerated to facilitate mobilization (8). The first 2 weeks postoperatively focus on range of motion of the hip and knee, and gait training with assistive devices as necessary. At 2 weeks postoperatively, strengthening of the abductors, hip flexors, and quadriceps is added to the regimen.

In younger patients, or fractures with a subtrochanteric component, weight bearing may be protected initially, and advanced as desirable by the treating surgeon.

Complications

Complications of operations through this approach are generally related to the osteosynthesis, and these may be avoided somewhat with careful attention to achieving reduction and adherence to correct placement of implants.

Approach to the Distal Femur and Knee

Indications/Contraindications

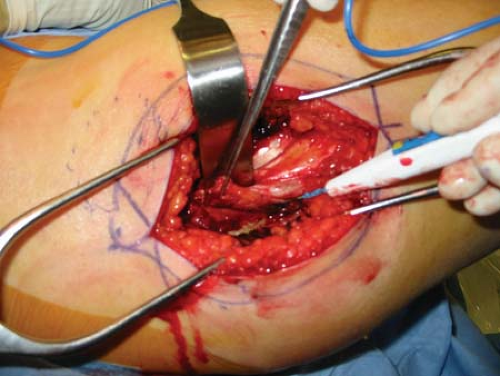

Multiple variations on parapatellar and lateral parapatellar approaches have been described. Similar to the muscle sparing approach described for the proximal femur, the “swashbuckler” approach described by Starr et al at Parkland Hospital (14) offers excellent visualization of the joint for anatomic fixation of interarticular fracture while preserving the vastus and quadriceps with no intramuscular dissection.

This approach offers the advantage of not interfering with or dividing the extensor mechanism while gaining adequate visualization of the joint space. With proximal and distal retraction, the intervening metaphyseal soft tissues may be largely undisturbed to enhance healing of comminuted metaphyseal bone.

Surgery

Patient Positioning

The patient is positioned supine. The lower extremity is prepared and draped free. A bump may be used under the knee to facilitate exposure and/or reduction.