CHAPTER 13 Soft Tissue Balancing

The use of a prosthetic system that adapts to the patient’s anatomy decreases the need for soft tissue balancing. In most cases, little additional soft tissue balancing is necessary after the steps of the procedure are followed as described in this textbook. Two notable exceptions exist. The first is in an individual, usually with a diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis or instability arthropathy, who has marked posterior glenoid wear and posterior glenohumeral subluxation on preoperative computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. The second is in an individual with an exceptionally tight posterior capsule, most commonly seen in our practice in patients with juvenile-onset inflammatory arthropathy.

EVALUATING THE NEED FOR SOFT TISSUE BALANCING

In patients with posterior glenoid wear (type B2 glenoid morphology; see Chapter 7), the sequence of surgical steps is altered. After the glenoid component is implanted, we insert the trial humeral prosthesis instead of the final humeral implant. This is helpful in judging prosthetic stability. After the trial humeral component is reinserted, the glenohumeral joint is reduced. With the arm externally rotated 30 degrees, force is applied in a posterior direction to the proximal humerus. There are two keys that allow the surgeon to determine whether the soft tissues are properly balanced. First, the prosthetic humeral head should subluxate posteriorly approximately 30% to 50% of its diameter and spontaneously reduce on release of the posteriorly directed force. If spontaneous reduction does not occur, posterior capsulorrhaphy may be necessary. Second, if posterior translation of at least 30% of the diameter of the humeral head is not possible, posterior capsular release may be necessary.

PERFORMING A POSTERIOR CAPSULORRHAPHY

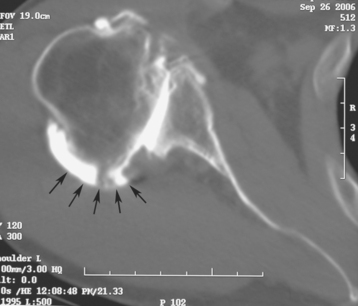

In many patients with posterior glenoid wear and posterior humeral head subluxation, the posterior capsule has become distended and ineffective in maintaining posterior glenohumeral stability, even after the osseous glenoid deformity has been corrected by reaming (Fig. 13-1). In such cases, posterior capsulorrhaphy serves to tighten the posterior capsule and prevent posterior instability. To perform this procedure, the trial humeral implant is removed and a laminar spreader with protective rubber sleeves on the tips is placed between the humerus and glenoid to expose the posterior capsule (Fig. 13-2). Three no. 1 braided absorbable sutures (one superior, one in the middle, and one inferior) are passed through the posterior capsule in a mediolateral direction to imbricate the posterior capsule (Fig. 13-3). The laminar spreader is removed and the sutures tied sequentially. The excess suture limbs are cut from the superior and middle capsulorrhaphy sutures, but the inferior suture is left uncut (Fig. 13-4). The sutures for subscapularis repair and the final humeral implant are placed (see Chapter 11) after posterior capsulorrhaphy, and stability is re-evaluated. Stability is usually greatly improved after posterior capsulorrhaphy. In the rare circumstance in which the glenohumeral joint remains dislocated on stability testing after posterior capsulorrhaphy is performed, the excess inferior suture limbs can be brought through the glenohumeral joint and rotator interval and sutured to the coracoacromial ligament just lateral to its insertion on the coracoid. This helps avoid posterior instability in the early postoperative phase (Fig. 13-5). Because these sutures are absorbable, no long-term consequence of passing the sutures through the glenohumeral joint have been observed when they have been necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree