THE NATURE OF SOCIAL PHOBIA

Social phobia is defined in DSM-IV as a ‘marked and persistent fear of social or performance situations in which embarrassment may occur’ (p. 411). For the diagnosis to be made the social or performance situation must almost always provoke immediate anxiety on exposure to the situation and the fear must interfere significantly with the person’s daily routine, occupational functioning or social life, or the person must be markedly distressed about having the disturbance. The social situation is normally avoided or it is sometimes endured with a sense of dread. Panic attacks may occur on exposure to, or on anticipation of, exposure to the phobic situation. In the feared situation people with social phobia are concerned about embarrassment and fear that others will judge them to be anxious, weak, crazy or stupid. There may be fear of eating in public because of concerns that others will see their trembling hands, or there may be great anxiety on conversing with others because of fear of appearing inarticulate or of showing anxiety such as blushing. In DSM-III-R and DSM-IV a generalised subtype of social phobia can be specified when the fears are related to most social situations, these individuals are more likely to show deficits in social skills and have more severe life impairment. A diagnosis of social phobia should not be given when the symptoms that are the focus of concern are the result of a medical condition, or when they are associated with another emotional disorder, for example concern about eating in front of others in anorexia nervosa.

A COGNITIVE MODEL OF SOCIAL PHOBIA

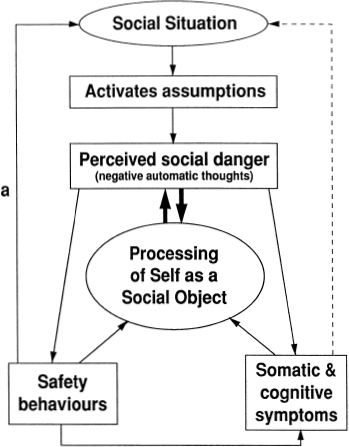

The role of negative self-appraisal processes in social phobia is developed in the cognitive model advanced by Clark and Wells (1995) and Wells and Clark (1997). This model accounts for the persistence of social phobia with reference to a number of cognitive-behavioural mechanisms. Central to the model is the view that social phobics seldom encounter situations that are capable of providing unambiguous disconfirmation of their fears. Even when social phobics regularly encounter their feared situations, their processing priorities, coping behaviours, and the nature of normal interpersonal transactions conspire to impede reduction in negative beliefs. Several vicious circles are therefore responsible for maintaining the problem. The model is presented in Figure 7.0.

Figure 7.0 A cognitive model of social phobia

The central feature of social phobia is a strong desire to convey a favourable impression of oneself to others, and this is accompanied by marked insecurity about one’s ability to do so. On entering social situations social phobics appraise the situation as dangerous. They believe that they are in danger of acting in an inept and unacceptable fashion and that such behaviour will have catastrophic consequences in terms of loss of status, rejection and humiliation by others. The fear of loss of status not only concerns the view held by others, but also concerns the socially anxious person’s perception of the self. These danger appraisals activate an ‘anxiety programme’ which consists of physiological, cognitive, affective and behavioural changes which, in the evolutionary past, were probably effective in reducing objective danger in primitive environments. However, in modern environments these anxiety symptoms are further sources of perceived danger since they are appraised as threatening the persons self-presentation skills and self- concept. This leads to an escalation of anxiety and a maintenance of the problem. Social phobics become preoccupied with their somatic responses, their negative thoughts concerning evaluation by others, and thoughts of negative self-evaluation. This preoccupation or heightened processing of the social self depletes attention to external aspects of the social situation in a way that makes social performance more difficult, and reduces awareness of objective interpersonal information. For example, social phobics may believe that they are the centre of attention or that people are bored with them in social situations but they are prone to pay little attention to other people in order to check this out. Social phobics focus on a self-generated perception of their performance in social situations and then mistakenly assume that this accurately reflects the way others perceive them. In order to prevent social catastrophe safety behaviours are used (e.g. Wells et al., 1995b) unfortunately these act in perpetuating belief in negative interpretations and anxiety. First, some of the safety behaviours used by social phobics when anxious exacerbate symptoms (e.g. holding a cup too tightly to reduce tremor can impede normal movements), or interfere with performance (e.g. mentally rehearsing what to say before saying it impairs concentration on conversation). Second, some of the coping or safety behaviours adopted can result in the social phobic appearing less warm and friendly to others, and thus safety behaviours have the effect of contaminating the social situation (line marked ‘a’ in Figure 7.0). Third, the non-occurrence of catastrophes in social situations can be mistakenly attributed to use of the safety behaviours rather than to the fact that appraisals are distorted.

A novel aspect of this approach is the model’s emphasis on the role of social self-processing which guides behaviour. This is essentially an impression of how the social phobic thinks he/she appears to others. The content of this impression contributes to the degree of danger appraised in social encounters. Implicit in the model is the notion that individuals are normally motivated to maintain a positive and stable public self-image. However, because of the mechanisms outlined, the social phobic’s concept is unstable and prone to fluctuation. Two other mechanisms contribute to this instability and heightened self-focus in social phobia: anticipatory processing, and post-event processing.

Anticipatory and post-event processing

In anticipation of problematic social encounters the social phobic tends to ruminate about the situation. This rumination may involve planning and rehearsing conversation and behaviour, and the content of the rumination is typically negative. It is at the anticipatory phase that the negative public self- concept is activated and the stability of the social self-concept is initially threatened. On leaving the social situation, exposure to the negative aspects of the encounter does not end. Social phobics are prone to mull-over aspects of the situation and their own behaviour. The problem with this post-mortem is that it does not provide any additional information that can be used to challenge negative beliefs. More specifically, because the social phobic was self-focused in the social situation, the most memorable aspect of the encounter is an image of the self or a felt-sense which is typically negative. The post-mortem contributes to an overemphasis on negative aspects of the encounter; a type of selective abstraction that prolongs negative affect. These thinking processes contribute to the maintenance of negative appraisals and beliefs.

Processing of the social self

When the social phobic enters an anxiety-provoking social situation there is a shift of attention towards processing the self. This self-relevant processing is often from an observer perspective (Wells, Clark & Ahmad, 1995a). That is, social phobics see themselves as if from another person’s perspective. This often occurs as an image of the way the social phobic believes they look to others or as a felt sense. The impression of the observable self is derived from interoceptive information—that is, from bodily sensations, feelings and observation of one’s own performance. This internal information often presents an inaccurate picture of the way social phobics actually appear to others. For example, if a social phobic feels shaky there may be an image of looking like ‘a jibbering wreck’, or if the phobic feels hot and is sweating, there may be an image of rivers of sweat running from the face.

Assumptions and beliefs

When symptoms happen: the meaning of failed performance

Unlike panic disorder in which the catastrophe does not occur, social phobia is a disorder in which negative feared events can happen. For example, people do stare, one can be rejected, humiliated, and found to be uninteresting.

However, the principal problem is not that these events do happen, since they happen to non-social phobics as well, but it is the meaning of these events for the individual, and the heightened perception of the likelihood of negative outcomes that presents the problem. We have seen how social phobia in the present model is associated with distorted self-perception which is a central target for treatment. However, social phobia is also characterised by distorted ‘other-perception’. For example, the social phobic believes that everyone will notice them and judge them negatively, which will lead to rejection. It is necessary to trace the meaning and implication of specific fears so that the nature of danger inherent in social phobic appraisals can be identified. Such an analysis elicits a string of meanings or predictions that are amenable to modification in cognitive therapy. Initial negative automatic thoughts (e.g. ‘I’ll tremble or shake’; ‘I’ll get my words wrong’) do not provide explicit meanings, and are difficult to challenge since they represent a self-commentary on one’s own symptoms that are likely to be factual. Cognitive therapy should focus on modifying the distorted self-image concerning how these responses look, and on challenging beliefs concerning the consequences of showing symptoms or of ‘failed performance’.

In the Clark and Wells (1995) model dysfunctional beliefs and assumptions render the individual vulnerable to the range of cognitive and behavioural factors that maintain social phobia. Three types of information are conceptualised at the schema level: (1) core self-beliefs (e.g. ‘I’m boring’; ‘I’m weird’); (2) conditional assumptions (e.g. ‘If I show I’m anxious people will think I’m incompetent’; ‘If I get my words wrong people will think I’m foolish’); (3) rigid rules for social performance (e.g. ‘I must always sound fluent and intelligent’; ‘T must not show signs of anxiety’). The pattern of onset of social phobia may be linked to the particular types of schema that exist (Wells & Clark, 1997). For example, individuals who have rigid rules for social performance may function with minimal anxiety throughout life until they encounter an event that leads to an important failure in meeting these standards. Following a critical incident of this type, social situations are perceived as more dangerous and carry with them, the potential of further ‘failures’. In contrast, pre-existing early dysfunctional conditional assumptions, which may be learned through interactions with family and the peer group, and unconditional negative beliefs, may underlie more longstanding problems of social anxiety.

Summary of the model

In summary, the cognitive model of social phobia proposes the following sequence of events when a social phobic enters a feared social situation: The situation activates assumptions concerning potential performance failure and the implications of showing anxiety symptoms. This leads to a perception of social danger which is evident as anticipatory worry or negative automatic thoughts. Examples of negative automatic thoughts are presented in Table 7.0.

Table 7.0 Examples of negative automatic thoughts, self-processing, and safety behaviours across five social phobics

| Negative automatic thoughts | Self-processing | Safety behaviours |

| 1. I don’t know what to say. People will think I’m stupid | Self-conscious: Image of self as a plain, unintelligent ‘bimbo’ | Avoid eye contact, don’t draw attention to self, say little, let partner do the talking, plan what to say, pretend to be interested in something |

| 2. I’ll shake and lose control. Everyone will notice me | Self-conscious: ‘The shaking feels so bad so it must look bad.’ Image of self-losing control | Avoid cups and saucers, grip objects tightly, move slowly, tense arm muscles, take deep breaths, try to relate, avoid looking at people, hold cups with both hands, rest elbows on table |

| 3. What if I get anxious? People will notice and not take me seriously | Self-conscious: Image of self as a bright red jibbering wreck with hands and arms ‘jingling’ about | Grip hands together, stiffen arms and legs, look away, ask questions, cover face with hair, wear extra make-up |

| 4. What if I sweat? They will think I’m abnormal | Self-conscious: Image of beads of sweat on forehead and top lip and hair looking soaked | Wear T-shirt under shirt, keep jacket on, use extra deodorant, wear light colours, hold handkerchief, keep arms next to body, wear cool clothes |

| 5. I’ll babble and get my words wrong. People will think I’m stupid | Self-conscious: Is aware of own voice and hears self as timid, weak and pathetic | Monitor speech, try to pronounce words properly, rehearse sentences mentally before saying them, speak quickly, ask questions, say little about self |

Negative automatic thoughts are associated with anxiety activation which is manifested in the form of somatic and cognitive symptoms. These symptoms are themselves subject to negative appraisal and may be interpreted as evidence of failure and social humiliation. Appraisals of danger are accompanied by a shift in attention in which the social phobic engages in detailed self-observation and monitoring of sensations, images and a ‘felt-sense’ (examples of self-processing are given in Table 7.0). This interoceptive information is used to make inferences about how the social phobic appears to others and how others are evaluating them.

In an attempt to conceal or avert social catastrophe safety behaviours are used (see Table 7.0) but these serve to maintain the problem. Safety behaviours contribute to:

- Heightened self-focus

- Prevention of disconfirmation

- Feared symptoms (e.g. sweating, mental blanks, trembling)

- Drawing attention to the self

- Contamination of the social situation (e.g. make the phobic appear aloof and unfriendly).

In some instances the feared social situation is avoided altogether. This is a problem because it removes opportunities for disconfirming negative appraisals and beliefs. Anticipatory processing in the form of worry and postevent worry (the post-mortem) contribute to problem maintenance by priming negative self-processing prior to social encounters, and by maintaining preoccupation with feelings and the distorted self-image after social encounters.

FROM COGNITIVE MODEL TO CASE CONCEPTUALISATION

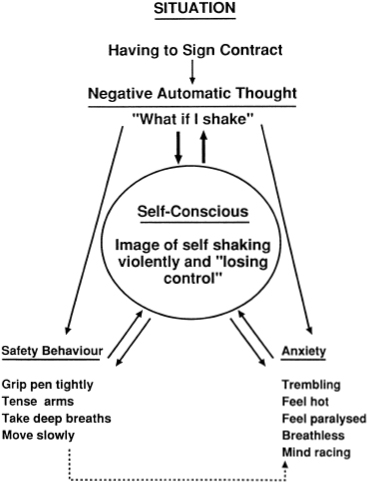

Figure 7.0 should be used as a template for building an individualised case conceptualisation. Initially the items in the lower part of the model incorporating feedback loops are conceptualised and the inclusion of assumptions is postponed until later in treatment. Essentially, the initial formulation represents the factors thought to be responsible for maintaining ‘in-situation’ dysfunctional self-processing and situational danger appraisals. The conceptualisation depends on eliciting the nature of safety behaviours and avoidance, the cognitive-somatic symptoms of anxiety, and the nature of self-processing. The situational shift to self-processing is marked by intensified self-consciousness. A modification of the model depicted in Figure 7.0 for case conceptualisation purposes, consists of including the term anxiety with cognitive/somatic responses, and includes the term self-consciousness with self-processing. Socially phobic individuals are better able to relate to these terms and therefore the model becomes more amenable to them. An idiosyncratic case conceptualisation of a 40-year-old female social phobic with a fear of writing and drinking in public is displayed in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 An idiosyncratic social phobia case conceptualisation

Eliciting information for conceptualisation

There are two basic approaches to eliciting data for conceptualisation: reviewing several recent episodes of social anxiety; or using direct questioning during or following exposure to a real or analogue situation. In some cases, specifically where there is marked avoidance of social situations, it is not possible to review a recent social anxiety episode in the detail required for conceptualisation. If this is the case, an analogue social phobic situation should be constructed in the therapy session. Depending on the nature of the patient’s fear this will typically involve introducing objects and/or other people into the consultation. For example, this involves drinking water from cups and saucers, talking in front of a small group, making conversation with a stranger, or talking to someone in authority. It may be necessary to expose to a real-life feared situation if the situation is so specific that it cannot be effectively duplicated in the treatment setting.

Collecting data for formulation

With the basic model in mind, treatment proceeds by eliciting the data necessary for constructing a cross-sectional situational model linking negative automatic thoughts, safety behaviours, anxiety symptoms, and the contents of self-focused attention (self-consciousness). Thus, four types of information are required initially: (1) main negative automatic thoughts; (2) safety behaviours; (3) anxiety symptoms; and (4) contents of self-consciousness.

Negative automatic thoughts

Negative automatic thoughts occurring in anticipation of exposure to feared situations, and automatic thoughts occurring in-situation should be elicited. Typically, thoughts occurring at both intervals reflect similar themes. While automatic thoughts may be readily accessible in the patient’s account of social anxiety episodes in response to questions such as ‘What negative thoughts went through your mind when you entered the situation?’, it is helpful to focus questions on the time of occurrence of anxiety or problematic symptoms: ‘When you noticed yourself feeling hot, what thoughts went through your mind?’ This serves to focus the interview on relevant automatic thoughts, and assists the patient in disclosing thoughts about symptoms which he/she might otherwise be embarrassed to mention. The following dialogue illustrates a review of a recent situation and elicitation of negative automatic thoughts:

In the example presented above negative automatic thoughts for a recent anxiety episode centred on themes of not knowing what to say in situation, and sounding stupid, as a consequence being viewed as boring. In this example the meaning or implication of the automatic thought ‘What if I can’t think of anything to say’ becomes clear in the course of therapist questioning. The meaning of automatic thoughts is not always apparent. In particular, when thoughts represent commentaries on symptoms—for example, ‘What if I sweat’; ‘I’m shaking’; ‘What if I blush’; ‘My voice is quivering’—it is necessary to explore the meaning of these symptom experiences. The cognitive model suggests that two types of meaning are relevant to problem maintenance. The first refers to the meaning and significance that other people might attach to symptoms, and the second relates to the individual’s own appraisal of the significance of symptoms such as overestimations of conspicuousness and self-concept implications. Thus, in eliciting negative automatic thoughts the meaning of such thoughts should be clearly identified. It is the meaning or implication of negative automatic thoughts or symptom experiences that are the focus of reattribution, not the statement of the symptom experience itself.

Anxiety symptoms

Symptoms of anxiety in social phobia are maintained by negative appraisals, and symptoms are often a focus of negative appraisals. Anxiety symptoms can be divided into physiological responses and cognitive responses. In social phobia the symptoms that tend to be most problematic are those which may be observable to others, such as blushing, shaking, sweating, muscle spasm, babbling, quivering voice, crying, and mind going blank.

In constructing the idiosyncratic conceptualisation the therapist should determine the nature of anxiety symptoms and determine the extent to which appraisal of symptoms contributes to negative automatic thought and dysfunctional self-processing. To this end questions like the following should be used:

- Which symptoms bother you most?

- When you felt anxious in the situation what symptoms did you notice?

- How conspicuous do you think the symptoms are?

- If people did notice your symptoms what would that mean?

Eliciting contents of self-processing

At the heart of the cross-sectional conceptualisation is the social phobic’s processing of the self as a social object. The content of self-processing can be determined through at least three channels: (1) exploring the contents of heightened self-consciousness; (2) questioning the social phobic’s appraised level of conspicuousness of symptoms; (3) determining if safety behaviours are linked to a particular self-perception.

The initial marker for self-processing in patient accounts of situations is a report of increased self-consciousness. The therapist should specifically ask about the point in time at which the patient became highly self-conscious. The main questions then are:

- When you were self-conscious, what were you most conscious of?

- What aspect of yourself were you most aware of?

- Did you have an impression of how you looked in the situation?

Often symptoms of anxiety are the focus of self-consciousness. Therefore questioning the subjective impression of the self for periods when symptoms are intense should be undertaken:

- When you felt anxious, what symptoms were you most aware of?

- Did you have an impression of how apparent your symptoms were to others?

- How do you think you appeared?

- If I could have seen you at that time—what would I see?

The content of self-processing is also accessible through a safety-behaviours channel. In particular, when safety behaviours are attempts to conceal symptoms or appraised personal shortcomings they are typically associated with a negative public impression of the self. For example, the social phobic who hides his/her face is likely to have an exaggerated impression of the anxious features that need to be hidden. Two questions are useful in the safety-behaviours channel: the first explores self-processing associated with implementing safety behaviours, and the second explores self-processing in the hypothetical absence of safety behaviours:

- When you try to conceal your symptoms, what’s your impression of how you look to others?

- If you didn’t engage in your safety behaviours when you felt anxious, how would you look to others?

Ask about imagery

The precise nature of a public self-impression should be determined. The impression often occurs as an image from the ‘observer’ perspective. If this is the case, the social phobic should be encouraged to regenerate a recent negative observer image and describe the image of the self in detail. In questioning the nature of the self-impression it is important to specifically ask:

- Did you have an image of the way you thought you looked when you were in the situation? Describe the image.

- Can you construct an image of how you think you looked at the time? Describe what you see.

Identifying safety behaviours

Safety behaviours in social phobia can be overt or covert. Examples of safety behaviours are presented in Table 7.0. Overt safety behaviours are often observable and can be seen during exposure tests.

If safety behaviours have been used for a long time period they may be less accessible to immediate conscious disclosure by the patient. In such circumstances exposure to the feared situation in conjunction with therapist- directed questioning probing the use of such responses is recommended. Particular attention should be given to eliciting covert safety behaviours such as ‘blanking out’ or mental rehearsal of sentences before speaking as part of the assessment and conceptualisation process. The following questions should be used to determine safety behaviours:

- When you thought (feared event) was happening, did you do anything to prevent it? What did you do?

- If you hadn’t done (safety behaviour), how much do you believe that (feared event) would have happened?

- Do you do anything else to control your symptoms/improve your performance/hide your problem?

- Do you do anything to avoid drawing attention to yourself?

- What is the effect of using your safety behaviour?

— What effect does it have on your self-consciousness?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree