CHARACTERISTICS OF PANIC ATTACKS

Panic attacks are defined as rapid occurrences of anxiety or rapid escalations in current anxiety in which there are at least 4 of 13 somatic or cognitive symptoms (DSM-IV; APA, 1994). Four or more symptoms have to escalate or occur within a ten-minute period, to meet panic criteria. These symptoms include physical responses such as palpitations, dizziness, sweating, choking, trembling or shaking, breathlessness, depersonalisation, and cognitive symptoms such as fear of dying, suffocating, going crazy, and so on. In some instances fewer than four symptoms occur in an attack, and these are known as limited symptom attacks but the distinction is somewhat arbitrary. Panics can also be differentiated in a way that relates to the conditions under which they occur. More specifically, panics may be situational (cued) or spontaneous (uncued). Spontaneous panics occur unexpectedly, while situational panics occur in situations that almost always cause anxiety. In order for an individual to meet criteria for panic disorder in accordance with DSM-IV (APA, 1994), the presence of recurrent, unexpected panic attacks followed by at least one month of persistent concern about having another panic attack or a significant behavioural change related to the attack is required. At some time during the problem there should have been at least two spontaneous panic attacks (which did not occur in anticipation of, or on exposure to, a situation which invariably caused anxiety). In addition it is important to establish that organic factors are not maintaining the problem. Organic factors which should be ruled out include: caffeine or amphetamine intoxication, and hyperthyroidism. Panic attacks occur in disorders other than panic disorder; for example, a social phobic or claustrophobic may panic on exposure to the feared situation.

Panic attacks can be nocturnal in which case an individual may wake from sleep in a state of intense anxiety. Panic commonly occurs in conjunction with agoraphobia, although not all agoraphobics have panic attacks or meet criteria for panic disorder. Agoraphobic avoidance develops in cases of panic disorder when individuals avoid situations in which they fear they might have another panic attack. The avoidance can lead to a highly restricted lifestyle in more severe cases. Panic disorder with agoraphobia is diagnosed when a person who meets diagnostic criteria for panic disorder is also agoraphobic. Agoraphobia is defined in DSM-IV as: ‘Anxiety about being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult (or embarrassing) or in which help may not be available in the event of having an unexpected or situationally predisposed panic attack’ (p. 396).

COGNITIVE MODEL OF PANIC

There are several cognitive models of the development and maintenance of panic disorder and agoraphobia (e.g. Goldstein & Chambless, 1978; Beck, Emery & Greenberg, 1985; Clark, 1986). The approaches of Clark (1986) and Beck and associates (1985) are based on the principle that panic patients fear the experience of certain bodily or mental events. Goldstein and Chambless (1978) offer a more learning theory based account of this ‘fear of fear’ concept. Their approach is analogous to the concept of interoceptive conditioning (Razran, 1961) in which bodily sensations become conditioned stimuli for the conditioned response of panic. However, Goldstein and Chambless (1978) add more cognitive elements to this concept. They assert that, having suffered one or more panic attacks, patients become ‘hyperalert’ for bodily sensations and interpret these as a sign of oncoming panic. Since these feared stimuli are carried around with the patient there is a generalisation of fear and external situations themselves become anxiety provoking, thus contributing to agoraphobia. The interoceptive conditioning approach has led to the development of treatments that attempt to extinguish fear of fear by strategies such as systematic exposure to internal sensations (e.g. Griez & van den Hout, 1986).

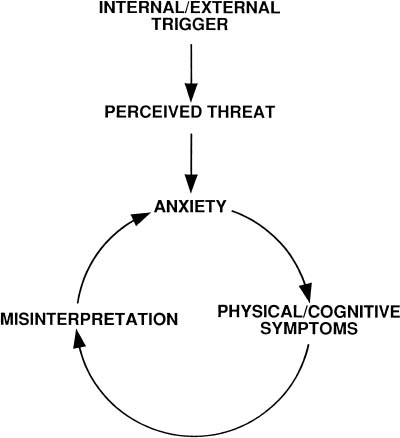

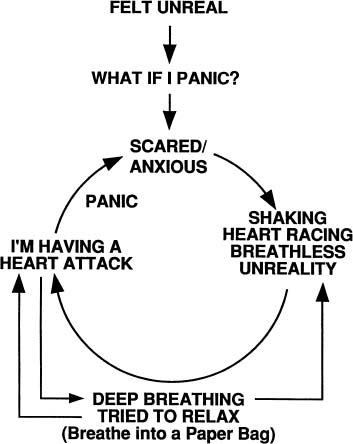

The model of panic proposed by Clark (1986) is one of the most useful for the cognitive conceptualisation and treatment of the disorder. The model has many overlapping features with the generic cognitive theory of anxiety proposed by Beck et al. (1985), and it deals specifically with the cognitive factors involved in the aetiology and maintenance of panic. More specifically, Clark’s (1986, 1988) model proposes that a certain sequence of events leads to panic attacks. This sequence is circular and the model has become known as the ‘vicious circle model’ of panic. However, vicious circles are useful for conceptualising anxiety disorders in general, although the precise pattern of cyclical relationships and the elements within cycles differs between disorders. In Clark’s model, panic attacks result from the ‘catastrophic misinterpretation’ of bodily or mental events. These events are misinterpreted as a sign of an immediate impending disaster, such as the sign of having a heart attack, of collapsing, suffocating, or going crazy. For example, physical sensations such as dizziness may be interpreted as a sign of fainting, and speeded heart rate as a sign of a heart attack. Mental events such as difficulty concentrating or the experience of racing thoughts can also be misinterpreted, often as a sign of a mental or social catastrophe such as losing control of one’s mind or behaviour. According to the model the sensations that are misinterpreted are mainly those associated with anxiety, but other non-anxiety sensations may also be misinterpreted. Non-anxiety sensations include feelings of shakiness or lightheadedness caused by low blood sugar, the sensations associated with postural changes in blood pressure, effects of alcohol withdrawal, tiredness, and so on. Many normal bodily sensations or deviations in physiological activity can become the target of misinterpretation. The vicious circle that culminates in a panic attack consists of a sequence of thoughts, emotions, and sensations which can begin with any of these elements. The basic model is presented in Figure 5.0.

In this model any internal or external stimulus which is appraised as threatening produces a state of anxiety and bodily symptoms associated with that state. If these symptoms are interpreted in a catastrophic way a further elevation in anxiety occurs and the individual becomes trapped in a vicious circle that culminates in a panic attack. Once panic attacks have occurred at least three other factors contribute to the maintenance of the problem: (1) selective attention to bodily events; (2) in-situation safety behaviours; (3) avoidance (e.g. Clark, 1988; Salkovskis, 1991; Wells, 1990).

Figure 5.0 Clark’s cognitive model of panic (adapted from Clark, 1986)

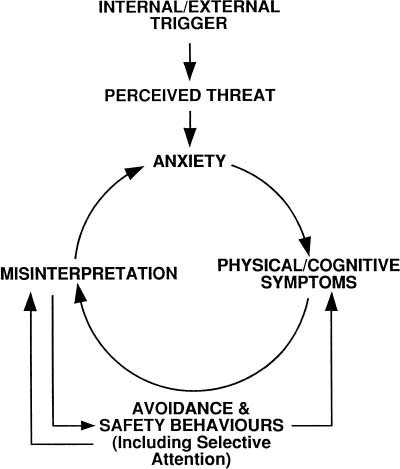

Selective attention to bodily events and increased bodily focus can contribute to a lowered threshold for perceiving sensations and may also be involved in increasing the subjective intensity of these events. As a result the patient is more likely to activate the cycle of misinterpretation. Panic patients develop situational safety behaviours aimed at preventing feared catastrophes. These responses prevent disconfirmation of belief in catastrophe and can intensify bodily symptoms. For example, patients who misinterpret feelings of weakness in the legs as a sign of imminent collapse may sit down, hold onto or lean on something, crouch down, put themselves on the floor, or tense the muscles in their legs in order to prevent collapse. The symptom intensification effect of safety behaviours is most evident in panickers who misinterpret breathlessness or shallow breathing as a sign of suffocating, and take deep breaths, or try to control breathing in order to avert the feared catastrophe. These control behaviours can lead to symptoms of hyperventilation: dizziness, dissociation, heightened breathlessness, etc. In summary, safety behaviours maintain panic in two ways. First, they prevent disconfirmation of the patient’s belief in misinterpretations, since the non-occurrence of the feared catastrophe can be falsely attributed to the use of the safety behaviour rather than correctly attributed to the fact that anxiety does not cause physical catastrophes such as collapsing. Second, certain safety behaviours directly exacerbate physical and cognitive symptoms which can make catastrophe more believable. Finally, avoidance is a maintaining factor in panic. Avoidance of anxiety-provoking situations, such as crowded shops, or activities such as exercise restrict the panicker’s opportunity to experience anxiety and to discover that it does not lead to catastrophe. These maintaining factors should be fully explored and included in idiosyncratic case conceptualisations. Figure 5.1 presents the basic model with these additional maintenance cycles incorporated.

Figure 5.1 Cognitive model of panic with maintenance cycles added

FROM COGNITIVE MODEL TO CASE CONCEPTUALISATION

The model presented in Figure 5.1 is directly translatable into an individual conceptualisation of panic attacks. The cognitive therapist has this model in mind when conducting the cognitive-behavioural assessment interview. In the next section specific assessment issues pertaining to the derivation of the panic model are considered.

Assessment

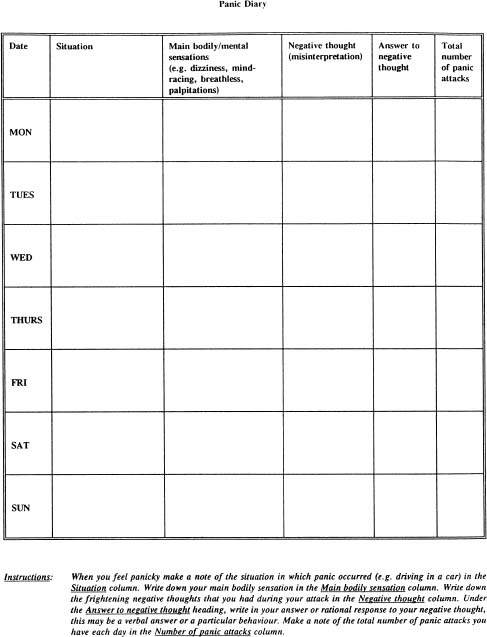

Cognitive-behavioural assessment in panic is aimed at eliciting idiosyncratic data for construction of a vicious circle model. The main information sought concerns: (1) the nature of catastrophic misinterpretations (content and belief levels); (2) detailed descriptions of the main feared sensations; and (3) the nature of safety and avoidance behaviours. One of the main outcome measures in the treatment of panic should be a measure of panic frequency and intensity, although measures of general anxiety (the Beck Anxiety Inventory) and of avoidance should also be used on a regular basis. Recommended measures are reviewed in Chapter 2. Panic frequency data can be collected in the form of a daily panic diary (see Figure 5.2 for an example of such a diary). Sessional use of the Panic Rating Scale presented at the back of this book is recommended for tracking change in symptoms, target safety behaviours and misinterpretations.

In the first few treatment sessions the conceptualisation may consist only of the primary vicious circle and the other contributory influences of safety behaviours may be omitted for simplicity and to facilitate patient understanding. However, whenever possible a full model of the symptomatic problem should be derived in the first session. Any conceptualisation of vulnerability factors (general beliefs and assumptions) and their inclusion in a more detailed cognitive conceptualisation should normally be postponed until a reliable cessation of panics is achieved.

DERIVING THE VICIOUS CIRCLE

The construction of the panic circle depends on identifying the sequence of events involved in specific panic attacks. Difficulty in the identification of misinterpretations and sequence involved arises from several sources: focusing on panic in a general abstract way; the presence of high degrees of patient avoidance behaviour leading to inaccessibility of ‘hot cognitions’; and a failure to slowly ‘track’ the course of attacks. Difficulties are minimised by identifying a specific and recent panic attack, and analysing it in detail as if it had occurred in ‘slow motion’. The vicious circle contains three basic elements: emotional reactions; bodily sensations; and negative thoughts about sensations (misinterpretations). These elements are linked in a sequence which follows a particular pattern which can begin with any one of the elements but always follows the same circular sequence:

Figure 5.2 Example of a panic diary

sensations thought → emotion → sensations thought → emotion, etc.

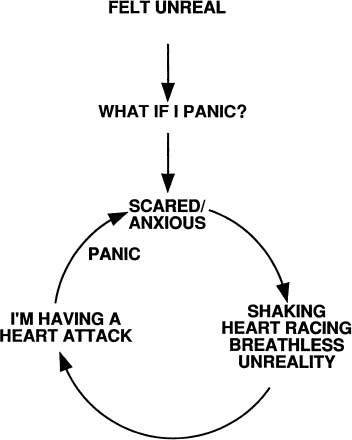

As illustrated in Figure 5.0, the vicious circle closes following the misinterpretation of bodily sensations associated with anxiety. The stem that leads to anxiety (apprehension) at the apex of the vicious circle can vary in length, and may consist of a chain of thoughts, sensations, or emotions other than anxiety such as anger or excitement. When constructing the panic circle it is most convenient to locate anxiety at the bottom of the stem so that it becomes the start of the circle. With anxiety in this location it is more convenient for closing the circle. An example of an idiosyncratic panic circle derived from a 26-year-old male panicker is displayed in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3 An idiosyncratic panic cycle

The therapist-patient socratic dialogue used to elicit the information for this conceptualisation was as follows:

The standard sequence of questioning illustrated above allowed the therapist and patient to identify the components of the panic cycle. In this case the trigger was feeling unreal, the quick negative automatic thought in the vicious circle stem was ‘What if I panic?’. This led to the emotional response of anxiety and then to associated sensations (heart racing, etc.), and then the catastrophic misinterpretation (I’m having a heart attack) which culminated in further anxiety and panic. This sequence is illustrated in Figure 5.3. Note that panic is actually labelled on the vicious circle, so that it is clear to patients. In this example the therapist elicited the patient’s belief in the misinterpretation during the panic attack. Belief ratings are essential, since therapy is focused on directly challenging and eliminating belief in misinterpretations. Changes in the level of these ratings are therefore an essential guide in determining the effectiveness of interventions used in cognitive therapy.

DEVELOPING THE BASIC CONCEPTUALISATION : INCORPORATING SAFETY BEHAVIOURS AND AVOIDANCE

Once the basic panic circle has been constructed, the next stage is the identification and inclusion of behaviours. Avoidance behaviours may be clearly apparent from the outset, particularly if agoraphobia is a problem. However, more subtle forms of avoidance and safety behaviours may be less apparent, and they should be carefully explored. Examples of subtle avoidance include avoidance of strenuous activity or exercise, avoidance of being alone, avoidance of medical information and so on. In most instances asking the question ‘Are there any situations that you are avoiding because of your anxiety?’ is sufficient to elicit some avoidance behaviours. This should be followed by other questions probing for detailed information about avoidance in an attempt to develop a comprehensive list of feared and avoided situations associated with panic. Self-report inventories such as the Marks and Mathews (1979) Fear Questionnaire and the Panic Rating Scale (Chapter 2) are aids to identifying avoided situations.

The identification and analysis of safety behaviours proceeds with questions designed to access the behaviours which the patient believes have prevented feared catastrophes from happening during anxiety / panic attacks. These behaviours can be elicited with questions about panic attacks in general, but the best strategy is the use of questions which probe safety behaviours in specific attacks already conceptualised. An example, of a dialogue used to elicit safety behaviours in the panic case presented previously follows:

Behavioural responses should be included in the initial panic cycle as a secondary positive feedback loop. The full formulation for this particular patient, which includes the behavioural loop, is presented in Figure 5.4.

The behavioural loop should be drawn as originating from the misinterpretation, and generates two potentially positive feedback influences: one is an exacerbation of bodily sensations, and the second denotes the prevention of disconfirmation of belief in misinterpretation. When the model has been presented in this form behavioural experiments should be used to illustrate the symptom intensification linkage, and metaphors can be used to illustrate the blocked disconfirmation linkage. Examples of these socialisation procedures are presented later in this chapter.

For purposes of clinical reference, examples of misinterpretations and safety / avoidance behaviours for a sample of seven patients treated by the author with a primary diagnosis of panic disorder with no to moderate agoraphobic avoidance (DSM-IV; APA, 1994) are presented in Table 5.0

Figure 5.4 A full idiosyncratic panic cycle

SOCIALISATION

Socialisation begins with building and presenting the panic cycle. This should be done for several panic attacks (to show that all panics fit the sequence). At this stage it is important to determine the patient’s reaction to the model, and to this end questions like the following should be used:

- Does this seem to fit with your experience of panic (if not why not)?

- Is there anything in the model which you feel is not right or you don’t understand?

The aim of socialisation is to offer an explanation of panic attacks as caused by the catastrophic misinterpretation of bodily sensations. These two variables can be linked by explaining that belief in catastrophe leads to an ‘adrenalin rush’ which exacerbates anxiety. The arrows in the model which occur after appraisals are usefully described as adrenalin surges. Where possible, behavioural experiments should be used to gain evidence in support of the model and illustrate linkages between its components.

Table 5.0 Examples of main sensations, misinterpretations and safety behaviours for seven panic patients

| Sensation(s) | Misinterpretation | Safety behaviour / avoidance |

| Palpitations Chest tightness | Heart attack Dying | Relax Slow down heart rate Sit down, avoid exercise Avoid physical exertion |

| Unreality (dissociation) | Loss of control Madness | Keep control of mind Check memory Try to control thoughts Look for exits |

| Breathlessness | Suffocate | Take deep breaths Sit by open windows Go into open air Suck menthol sweets |

| Throat tightness | Choking | Carry bottle of water Try to clear throat |

| Dizzyness | Fainting Collapsing | Control breathing Sit down Hold on to partner Avoid going out alone |

| Blurred vision | Blindness Stroke | Check vision Wear sunglasses Take aspirin Avoid stress |

| Jelly legs | Falling Collapsing | Leave situations Stiffen legs while standing Walk close to walls Wear flat shoes |

Sample socialisation experiments

The paired associates task

This task (Clark et al., 1988) aims to illustrate the effect of thinking on anxiety and associated bodily sensations by testing the supposition that thinking about physical catastrophes can elicit or heighten bodily sensations and/ or anxiety. The task is presented without an explanation of its aims, since a rationale can interfere with the impact of the task. The patient is asked to dwell on pairs of words and think of their meaning while reading them aloud. A period of about 5–8 seconds should be allowed for dwelling on each word pair, which are presented in list format. The words used for constructing the pairs consist of common anxiety sensations partnered with physical calamities typical of the content of panic misinterpretations. For example, the following word pairs would be repeated on the list:

| Breathlessness | — | Suffocate |

| Dizziness | — | Fainting |

| Chest tight | — | Heart attack |

| Numbness | — | Stroke |

| Palpitations | — | Heart attack |

| Unreality | — | Insane |

| Weakness | — | Collapsing |

After performing the task for a few minutes, the patient should be asked if he / she noticed anything while reading the words. Occasionally the task invokes high anxiety, but most often a more subtle increase in anxiety or awareness of bodily sensations is reported. The patient should then be asked what sense he / she makes of this result in terms of the model, and in terms of the impact of their thinking. The task does not work with all patients. When it fails, closure of the exercise can be achieved by explaining that it was a test to see what the patient’s general reaction was to reading unpleasant material, and the fact that there was little reaction is fine.

Body-focus task

A different demonstration of the effect of ‘thinking’, or more specifically the effect of selective attention on symptom perception, can be achieved with selffocused attention manipulations. The task serves to show that attentional strategies can increase awareness of bodily sensations which are normally present, and that it can exaggerate perceived symptom intensity. Patients are asked to focus attention on sensations in particular parts of the body such as the feet, or sensations in the fingertips. After a couple of minutes monitoring they are asked to report what is noticed. The procedure is normally used in conjunction with questions which facilitate the framing of the results of the task in terms of the panic model. Typical questions include the following:

- Were you aware of the sensations before you focused on that part of your body?

- What happened to the sensations when you focused on them?

- If focusing your thoughts on your body leads you to notice sensations that you were not previously aware of, how might that contribute to the vicious circle?

A variant of the self-focus task involves visual fixation on parts of the body, such as staring at the back of one’s left or right hand, and noticing what happens to perception, such as perception of size, clearness of the image, and extent to which the hand seems part of the individual. If there is evidence to suggest that a patient engages in this type of self-monitoring as a safety / checking behaviour this is likely to be a useful socialisation task since self-monitoring can exaggerate feared responses such as distortions in perception of size and feelings of unreality.

Increased safety behaviours tests

Safety behaviours can be manipulated in-session to demonstrate the role of behaviours in maintaining and intensifying sensations, and as an introduction to the concept of such behaviours preventing disconfirmation. For example, if a panicker uses deep controlled breathing to avert an appraised catastrophe such as suffocating, deliberate controlled deep breathing can be employed to illustrate the effect of this behaviour on sensations. A range of sensations can be produced by more vigorous over-breathing including: dizziness, palpitations, feelings of faintness, depersonalisation, blurred vision, feelings of weakness, etc. While it should be acknowledged that the patient probably does not breathe in such a vigorous way when panicking, it should be stressed that the exercise is intended to illustrate what can happen, and that even small changes in sensations produced by smaller changes in breathing tend to be more perceptible during panic attacks when fears are activated.

The effective use of increased safety behaviours tests relies on the detailed exploration of the actual behaviours used by the individual when anxious, and the selection of those which are likely to be involved in symptom intensification and thus can be used to illustrate the model.

Metaphors and allegories as socialisation

The effect of safety behaviours in preventing disconfirmation of belief can be illustrated with metaphors and allegories. Two examples are given below:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree