Snapping Hip Syndrome

J.W. Thomas Byrd MD

External coxa saltans is snapping due to the tensor fascia lata and iliotibial band flipping back and forth across the greater trochanter.

Internal coxa saltans is snapping caused by the iliopsoas tendon.

Intra-articular coxa saltans refers to a variety of intra-articular lesions that can cause painful clicking or popping within the joint.

Coxa vara and reduced bi-iliac width have been proposed as predisposing anatomic factors of external coxa soltans.

Symptomatic cases of external coxa saltans are most commonly associated

with repetitive activities, but may occur following trauma.

Snapping of the iliotibial band usually can be demonstrated by the patient better than it can be produced by passive examination.

Radiographs and further investigative studies are rarely of benefit except to assess for other associated disorders.

Surgical intervention rarely is necessary. Published results of a variety of surgical techniques to address recalcitrant snapping of the iliotibial band range from poor to excellent.

Snapping of the iliopsoas tendon can be difficult to differentiate from and may co-exist with intra-articular pathology.

Certain activities, such as ballet, have a tendency to develop snapping of the iliopsoas tendon as an overuse phenomenon.

Endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon seems to represent an excellent alternative to traditional open techniques for recalcitrant cases.

When treatment is necessary, most patients will respond to a proper conservative strategy.

“Coxa saltans” is a popular term to describe snapping syndromes around the hip, with an external, internal, and intra-articular type described (1). External coxa saltans is snapping due to the tensor fascia lata and iliotibial band flipping back and forth across the greater trochanter. Internal coxa saltans refers to snapping caused by the iliopsoas tendon. Intra-articular coxa saltans is a nonspecific term for a variety of intra-articular lesions that can cause painful clicking or popping emanating from within the joint.

Snapping of the iliotibial band is visually evident. The patient will describe a sense that the hip is subluxing or dislocating but radiographs show that the hip remains concentrically reduced despite the outward appearance.

Etiology and Pathomechanics

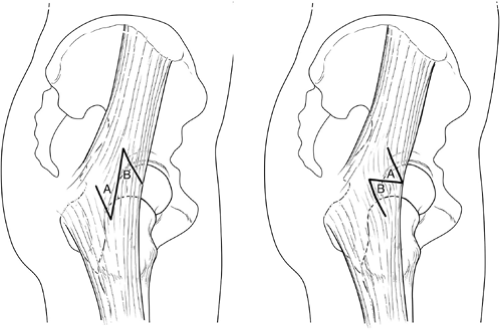

The snapping occurs as the iliotibial band flips back and forth across the greater trochanter (Fig 30-1). This is often attributed to a thickening of the posterior part of the iliotibial tract or anterior border of the gluteus maximus (1,2). Coxa vara and reduced bi-iliac width have been proposed as predisposing anatomic factors (3,4). Tightness of the iliotibial band may also be an exacerbating feature. This condition has classically been described in the downside leg of runners training on a sloped surface, such as a roadside (5). Some patients can demonstrate this phenomenon as an incidental asymptomatic maneuver. Symptomatic cases are most commonly associated with repetitive activities, but the snapping may occur following trauma. It has also been reported as a postsurgical iatrogenic process (6,7).

Assessment

The snapping or subluxation sensation described by the patient is a dynamic process that they can usually demonstrate better than it can be produced by passive examination. The symptoms and findings are located laterally and the patient can usually produce this best while standing. The snap can be palpated over the greater trochanter and applying pressure to this point may block the snap from occurring. The Ober test evaluates for associated tightness of the iliotibial band.

The diagnosis is usually clinically evident. Radiographs and further investigative studies are rarely of benefit except to assess for other associated disorders. Ultrasonography may help to substantiate the diagnosis, but is rarely necessary. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may demonstrate evidence of trochanteric bursitis or inflammation within the abductor mechanism.

Treatment

Once the diagnosis is established, most will respond to conservative measures. These include modification of activities to avoid offending factors, oral anti-inflammatory medication, therapeutic modalities, and a gentle stretching and conditioning program directed specifically at the iliotibial band. Corticosteroid injection in the trochanteric bursa does not resolve the snapping, but may alleviate the symptoms so other measures can be effective.

The published results of surgical intervention for recalcitrant snapping of the iliotibial band range from poor to excellent. Various techniques have been described, but it is generally accepted that the common goal, regardless of the method, is to eliminate the snapping by some type of relaxing procedure of the iliotibial band. The success of the operation may be less dependent on the exact technique as much as careful patient selection. In fact, the published results of the same operation among two different military populations ranged from “less than optimal” to “excellent and predictable” (8,9).

It is important to remember that snapping of the iliotibial band is usually a dynamic process, better demonstrated by the patient than observed by passive examination, and there may be a deliberate or voluntary component to this snapping phenomenon. Thus, the surgeon must carefully evaluate that patient’s motivation and emotional stability. The patient is causing no harm by living with the condition but, if they have exhausted all efforts at conservative treatment, then surgical intervention is an appropriate final step for select recalcitrant cases. The patient must be aware that, while the results of surgery may be successful at eliminating the snapping, there is a risk that they may still experience similar or different pain or dysfunction. For correctly diagnosed cases that do not respond to surgical intervention, it is unlikely that there is a reliable subsequent salvage procedure.

Most recent published literature has been based on the Z-plasty technique popularized by Brignall and Stainsby in 1991 (10) (Fig 30-2). They reported eight hips in six patients, mean age 19 years, all with resolution of the snapping and excellent pain relief. Three hips in two patients experienced occasional aching, and one patient underwent a second, more extensive Z-plasty in order to achieve a successful outcome. Faraj et al. (11) in 2001, reported on 11 hips in 10 patients, mean age 17.3 years. All experienced resolution of pain and snapping, although three patients developed painful scars requiring desensitization treatment for 2 to 6 months. In 2002, Kim et al. (8) reported on three active duty soldiers with a successful result in only one case. Conversely, a report by Proventure et al. (9) in 2004 included eight hips in seven active duty military personnel with six of the seven returning to full military duties. One underwent subsequent surgical intervention and was eventually medically discharged from the service. Of note, this study excluded an unknown number of patients who had other concomitant diagnoses, prior fracture, childhood hip pathology, or had undergone previous surgical procedures.

In 1986, Zoltan et al. (12) described seven athletic individuals treated with excision of an ellipsoid-shaped segment of the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter (Fig 30-3). All experienced resolution of the snapping, were able to return to sports activities, and considered themselves significantly

improved, although only three were asymptomatic. One patient underwent a subsequent revision procedure with further excision of the iliotibial band in order to achieve a successful outcome.

improved, although only three were asymptomatic. One patient underwent a subsequent revision procedure with further excision of the iliotibial band in order to achieve a successful outcome.

The largest single series was published by Larsen and Johansen (4) in 1986 with 31 hips in 24 patients who underwent resection of the posterior half of the iliotibial tract at its insertion with the gluteus maximus. The details of this study were brief, but they reported that 22 (71%) were pain-free, six (19%) had persistent snapping without pain, three (10%) had persistent snapping with pain, and there were no major complications. Two of the three with pain underwent revision surgery with good results.

In 1979, Brooker (13) described a cruciate incision of the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter as a successful method of management for severe trochanteric bursitis. William Allen from Missouri (personal communication, 1995) has proposed a modification of the cruciate incision in the management of the snapping iliotibial band. This is a method that these authors have employed which includes an 8 to 10 cm longitudinal incision just posterior to the midpoint of the greater trochanter in the thickest portion of the iliotibial band along with two pairs of 1 to 1.5cm transverse incisions (6) (Fig 30-4). Limited experience in five cases has resulted in complete resolution of the snapping, excellent patient satisfaction, and no complications. The advantage of this technique is that it is simple, it accomplishes the desired effect, it minimizes violation of the iliotibial band, and there are no repair lines that must be counted upon to heal. This also facilitates a liberal, although structured, postoperative rehabilitation program. Crutches are used only for comfort as the gait pattern is normalized, typically in 10 to 14 days. Gentle stretching and flexibility is emphasized, although aggressive stretching is not necessary.

Recent experience has begun to emerge on the role of trochanteric bursoscopy (14,15). A natural progression of this may be toward endoscopic release of the iliotibial band. The concern is either inadequate or excessive resection. Currently, the open method still seems to be better suited for quantitating the extent of tendinous release.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree