Concussion associated with sport is a common occurrence with an estimated 1.6 to 3.8 million sports-related concussions yearly in the United States. The sideline assessment of concussion focuses on four areas: cognitive ability, balance, associated symptoms, and visual tracking. Tools available on the sideline to assist in the diagnosis of concussion are discussed in this article. Some of these tools are validated and reliable and some are developing and have yet to be proven to be sensitive enough for routine use. These tools along with a thorough history and physical examination enable a sideline physician to accurately diagnose concussion.

Key points

- •

Concussion is a common occurrence in the athletic setting, and can be difficult to diagnose in a sideline situation.

- •

History and physical examination are important aspects of the evaluation of potential concussion with an emphasis placed on associated symptoms and a complete neurologic examination.

- •

The SCAT3 is a vital and important test that can be used on the sidelines to evaluate a potential concussion.

- •

There are other sideline tools to measure vision, reaction time, neurocognitive processes, and head impact/acceleration that are used in the sideline evaluation of concussion.

- •

An ideal sideline concussion evaluation test should be quick, cost effective, easy to administer, and reproducible.

Introduction

Concussion is defined as a complex pathophysiologic process affecting the brain caused by biomechanical forces. These forces can either be direct (eg, the head, neck, or face striking another object) or indirect (eg, impulsive forces transmitted to the head from a force somewhere else on the body). It is estimated that there are 1.6 to 3.8 million sports-related concussions in the United States on an annual basis. There is evidence that children (ages 5–18) may be more susceptible to concussion and can take longer to recover. It is also known that athletes who have experienced multiple concussions in the past may be more susceptible to future concussions, suffer subsequent concussions with less force, and potentially take longer to recover. Females may be more susceptible, and there may also be genetic traits that increase the risk of sustaining a concussion. Concussion rate varies by the sport with American football (3.02 per 1000 athlete exposures), ice hockey (1.96 per 1000 athlete exposures), and women’s soccer (1.80 per 1000 athlete exposures) being the most prevalent sports.

The onset of symptoms is rapid or delayed, making the diagnosis of concussion difficult in the acute setting. In addition, athletes may hide symptoms to continue playing. McCrea and coworkers in 2004 published a study that showed that 50% to 75% of sports concussions go unreported at the high school level. A study done in 2013 at the University of Pennsylvania by Torres and colleagues indicated that 43% of athletes had knowingly hidden a concussion from their athletic trainer or coach and 22% of athletes would be likely to hide a concussion again if the situation arose. The long-term and delayed effects of concussion are still a developing and controversial subject. However, there is evidence that exposure to repeated concussions can lead to prolonged symptoms, and may increase the risk of developing psychiatric illnesses, dementia, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. The clinical diagnosis of concussion is based on a variety of factors combined with a high degree of suspicion. There is no completely reliable sideline test that can replace clinical judgment. The sideline assessment of concussion is challenging at times; however, there are tools available to help in this process.

Introduction

Concussion is defined as a complex pathophysiologic process affecting the brain caused by biomechanical forces. These forces can either be direct (eg, the head, neck, or face striking another object) or indirect (eg, impulsive forces transmitted to the head from a force somewhere else on the body). It is estimated that there are 1.6 to 3.8 million sports-related concussions in the United States on an annual basis. There is evidence that children (ages 5–18) may be more susceptible to concussion and can take longer to recover. It is also known that athletes who have experienced multiple concussions in the past may be more susceptible to future concussions, suffer subsequent concussions with less force, and potentially take longer to recover. Females may be more susceptible, and there may also be genetic traits that increase the risk of sustaining a concussion. Concussion rate varies by the sport with American football (3.02 per 1000 athlete exposures), ice hockey (1.96 per 1000 athlete exposures), and women’s soccer (1.80 per 1000 athlete exposures) being the most prevalent sports.

The onset of symptoms is rapid or delayed, making the diagnosis of concussion difficult in the acute setting. In addition, athletes may hide symptoms to continue playing. McCrea and coworkers in 2004 published a study that showed that 50% to 75% of sports concussions go unreported at the high school level. A study done in 2013 at the University of Pennsylvania by Torres and colleagues indicated that 43% of athletes had knowingly hidden a concussion from their athletic trainer or coach and 22% of athletes would be likely to hide a concussion again if the situation arose. The long-term and delayed effects of concussion are still a developing and controversial subject. However, there is evidence that exposure to repeated concussions can lead to prolonged symptoms, and may increase the risk of developing psychiatric illnesses, dementia, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. The clinical diagnosis of concussion is based on a variety of factors combined with a high degree of suspicion. There is no completely reliable sideline test that can replace clinical judgment. The sideline assessment of concussion is challenging at times; however, there are tools available to help in this process.

Physical examination

After an athlete is suspected of suffering a concussion, the athlete should be held out of participation until assessed by a licensed health care professional. In an ideal situation, the team physician or athletic trainer, who are specifically trained in concussion diagnosis and management, would be present to assess and manage the injury. It is understood that there are many instances in which there is not an athletic trainer or physician on the sidelines, making it important for coaches and parents to be educated on the signs and symptoms of concussion. If there is concern for concussion, the athlete should not return to play and should be assessed by a health care professional as soon as possible. There are some signs/or symptoms that could warrant emergent transfer to a hospital including the following:

- •

Prolonged loss of consciousness

- •

Multiple episodes of vomiting

- •

Progressive worsening of symptoms

- •

Signs of a potential skull fracture

- •

Focal findings on neurologic examination

- •

Decreasing level of consciousness

If any of these symptoms are present, the emergency action system should be activated and the athlete should be transferred to the nearest hospital.

The initial part of the examination should focus on the potential injury to the cervical spine. If an athlete loses consciousness then a cervical spine injury should be assumed until ruled out. The cervical spine should be immobilized on the field and an immediate spine and neurologic examination should take place. If a cervical spine injury is suspected then the athlete should be transferred emergently via ambulance using a spine board for immobilization to the nearest hospital for further assessment and management. After ruling out a significant cervical spine injury on the sideline, neurologic examination should include the following:

- •

Cranial nerve function testing

- •

Upper and lower extremity neurologic examination with emphasis on sensation, reflexes, and strength

- •

Balance assessment

- •

Coordination assessment

- •

Evaluation of cognitive processing

The athlete should be monitored serially for worsening or change in symptoms. It is important that the athlete not be left alone at any time during this process. If available, an athletic trainer or team physician should stay with the athlete, although a parent, adult, or student may be used if necessary. If there is concern for worsening or a change in signs or symptoms then the athlete should be examined thoroughly again and appropriate measures should be taken. Serial evaluations every 30 minutes should take place until the athlete stabilizes or is transported to another health care facility. It is also appropriate to send the athlete home with instructions on care for concussion and the signs and symptoms to monitor. Many states require this type of notification to be provided to parents. Providers should review their state and local policy regarding parental notification. An example of these instructions is included next.

Watch for Any of the Following Problems

- •

Difficulty remembering recent events

- •

Slurring of speech

- •

Worsening headache

- •

Stumbling/loss of balance

- •

Vomiting

- •

Weakness in one arm/leg

- •

Decreased level of consciousness

- •

Blurred vision

- •

Dilated pupils

- •

Confusion

- •

Increased irritability

- •

Ringing in ears

An Example of Take Home Instructions

It is okay to use acetaminophen for headache or pain, use an ice pack for comfort, eat a light meal, and go to sleep. There is no need to check eyes with a light, wake up every hour, or stay in bed. Do not drink alcohol; drive a car; or use aspirin, ibuprofen, or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug products.

Under no circumstance should an athlete suspected of sustaining a concussion be allowed to return to play without being cleared by a health care professional. With that being said, precautions should be taken by those who care for athletes, and it is never wrong to withhold an athlete from competition if there is any question as to whether a concussion has occurred. No athlete should be allowed to return to play on the same day as sustaining a concussion, and there are now clear evidence-based guidelines about return to play that are supported by state law in every state. Health care professionals do have some validated and some unvalidated tools that could potentially aid in the sideline assessment of concussion, but these tools should not replace the importance of high clinical suspicion in the diagnosis of concussion.

Symptom checklist

The simplest and quickest way to assess for concussion is to do a symptom checklist. Also called a postconcussion symptom scale, this checklist contains common signs and symptoms that are associated with concussion. It consists of items that are scored on a seven-point Likert scale (0–6) with zero being asymptomatic and six being very symptomatic.

Symptoms associated with concussion can manifest in many different ways. Some of these symptoms are present on the sidelines and some both on the sidelines and in follow-up.

Somatic

- •

Headache

- •

Dizziness

- •

Balance disruption

- •

Nausea/vomiting

- •

Photophobia

- •

Phonophobia

- •

Blurry vision

Cognitive

- •

Confusion

- •

Anterograde amnesia

- •

Retrograde amnesia

- •

Loss of consciousness

- •

Disorientation

- •

Feeling mentally “foggy”

- •

Inability to focus

- •

Delayed verbal and motor responses

- •

Slurred/incoherent speech

- •

Excessive drowsiness

Affective

- •

Emotional lability

- •

Irritability

- •

Fatigue

- •

Anxiety

- •

Sadness

Sleep

- •

Trouble falling asleep

- •

Sleeping more than usual

- •

Sleeping less than usual

The first team to use this as an evaluation tool was the Pittsburgh Steelers of the National Football League. Since they adopted this symptom checklist approach multiple professional, colleges, and high schools across the country also have used it. The checklist can also be used to assess the progression of symptoms over a short or prolonged period of time, and can be used to determine when return to play can commence. The number of items on the checklist varies from 22 on the sport concussion assessment tool (SCAT), the Steelers version containing 17 items, and another common version called the concussion symptom inventory containing only 12 items. The presence of symptoms associated with concussion cannot diagnose a concussion but can lead to further evaluation or precautions before making return to play decisions.

Maddocks questions

The Maddocks questions have become a main component of sideline assessment of concussion and are included in the SCAT3 and standardized assessment of concussion (SAC,) which are widely used today. Maddocks and coworkers developed the questions to assess the sensitivity of orientation and recent memory in the diagnosis of concussion. The results show that items evaluating recently acquired information are more sensitive in the assessment of concussion than standard orientation items. The five questions focus on short- and intermediate-term memory and can be used on the sidelines of a game. The questions are as follows:

- •

Where are we?

- •

What quarter/half is it right now?

- •

Who scored last in the game/practice?

- •

Who did we play in the last game?

- •

Did we win the last game?

One point is given for each correct answer and zero points are given for each incorrect or incoherent answer. This is a simple tool that can be used by health care professionals, coaches, and parents that can help in the diagnosis of concussion and should be repeated serially every 30 minutes on the sidelines.

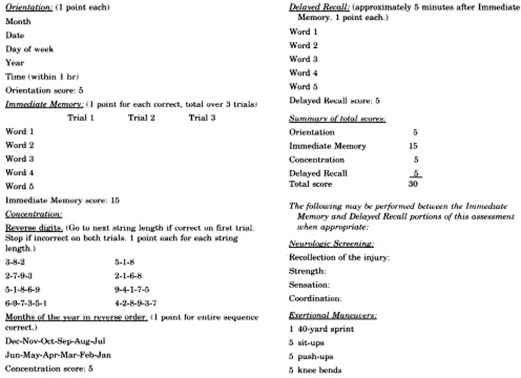

Standardized assessment of concussion

The SAC is a tool that has been developed to assess orientation, immediate memory, concentration, and delayed recall in an athletic setting. Fig. 1 shows a sample of the SAC. The SAC is separated into four sections. The first section tests orientation and is similar to the Maddocks questions. It consists of the following questions:

- •

What month is it?

- •

What is the date?

- •

What day of the week is it?

- •

What year is it?

- •

What time is it (within 1 hour)?