Shoulder Impingement

James Patrick Tasto MD

John K. Locke MD

In clinical frequency, shoulder pain is exceeded only by low back pain and neck pain. The most common source of shoulder pain originates in the subacromial space, with the most prevalent diagnosis being impingement syndrome.

Without treatment, symptoms will persist and usually progress.

Shoulder impingement has been described as “symptomatic mechanical irritation of the rotator cuff tendons from direct contact at the anterior edge of the coracoacromial arch.”

In the normal shoulder, the coordinated muscle tension within the rotator cuff compresses the humeral head, keeping it centered within the glenoid fossa. By coupling with the force of the deltoid, a fulcrum is created, generating strength through a wide arc of motion.

Any process that interferes with the rotator cuff’s capability to keep the humeral head centered or that compromises the normal coracoacromial arch, including calcium deposits, thickened bursae, and an unfused os acromiale, can lead to impingement of the rotator cuff.

Functional overload, intrinsic tendonopathy, and internal anatomic impingement have also led to shoulder impingement.

It is important to rule out other potential sources of shoulder pain, including: acromioclavicular arthrosis, rotator cuff tear, instability, adhesive capsulitis, biceps tendonitis, labral pathology, and cervical radiculopathy.

The x-ray views that are most helpful are anterior-posterior view, supraspinatous outlet view, and axillary lateral. A 15-degree cephalic view of the Acromioclavicular (AC) joint and an anterior posterior (AP) view with humeral internal rotation can also be helpful.

Nonoperative care is tried before surgical intervention is considered. The majority of patients can be treated conservatively. Treatment consists of physical therapy, activity modification, anti-inflammatory medications, and steroid injections into the subacromial space.

When nonoperative treatment fails, the procedure of choice is arthroscopic subacromial decompressions (ASAD). The advantages of arthroscopy include minimally invasive surgery without detachment of the deltoid.

Conventional postoperative pain control can generally be obtained with oral medications. Stiffness can be avoided when early motion is emphasized.

Through progressive steps in exercises, full active range of motion can usually be achieved within three to four weeks. Athletes using overhead motions should avoid sports for at least 3 months, and complete recovery can take 6 months.

The concept of mechanical impingement on the rotator cuff was popularized by Neer (1). He noted that with forward elevation of the arm, the rotator cuff tendons were subject to repeated mechanical insult by the overlying coracoacromial arch. He observed that impingement was a result of bony spurs at the anterior third of the acromion and the coracoacromial ligament. This concept of anterior impingement as opposed to lateral acromial impingement has been generally accepted.

Neer (2) reported the cause of most impingement to be due to an inadequate “outlet” and described this phenomenon as outlet impingement. The outlet is the space beneath

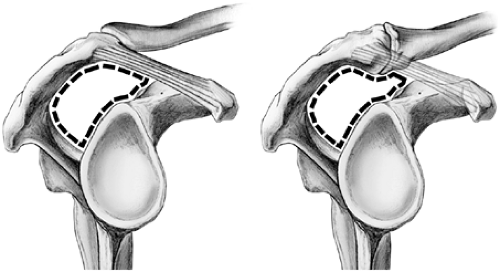

the anterior acromion, coracoacromial ligament, and acromioclavicular (AC) joint. Within this space, the rotator cuff tendons pass to their insertions on the tuberosities of the humerus. The superior border of the outlet forms an arch known as the coracoacromial arch. Any prominence that affects this arch may encroach on the outlet causing outlet impingement (3). In addition to outlet impingement, the terms subacromial, primary or external impingement are also used. The definition has more recently been described as “symptomatic mechanical irritation of the rotator cuff tendons from direct contact at the anterior edge of the coracoacromial arch” (4) (Fig 11-1).

the anterior acromion, coracoacromial ligament, and acromioclavicular (AC) joint. Within this space, the rotator cuff tendons pass to their insertions on the tuberosities of the humerus. The superior border of the outlet forms an arch known as the coracoacromial arch. Any prominence that affects this arch may encroach on the outlet causing outlet impingement (3). In addition to outlet impingement, the terms subacromial, primary or external impingement are also used. The definition has more recently been described as “symptomatic mechanical irritation of the rotator cuff tendons from direct contact at the anterior edge of the coracoacromial arch” (4) (Fig 11-1).

In the normal shoulder, the coordinated muscle tension within the rotator cuff compresses the humeral head, keeping it centered within the glenoid fossa (3). By coupling with the force of the deltoid, a fulcrum is created that allows strength through a wide arc of motion (5). The overlying subacromial bursae reduces friction between the tendonous cuff and the coracoacromial arch. With normal overhead movement, the bursae facilitates smooth gliding of the tendons within this limited space.

In most individuals, the space between the greater tuberosity and the undersurface of the acromion is approximately 7 to 14 mm while standing with the arm at the side (6). There is little room for clearance, and during normal overhead shoulder function light contact between the rotator cuff and coracoacromial arch may occur. Any process that interferes with the rotator cuff’s capability to keep the humeral head centered or compromises the normal coracoacromial arch can lead to impingement of the rotator cuff. This can include calcium deposits, thickened bursae, and an unfused os acromiale (7).

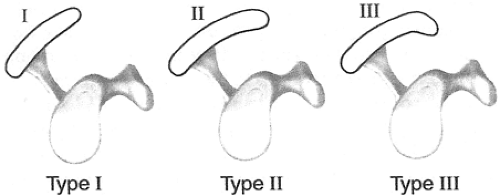

Specific acromial morphologies affect the size of the outlet. Bigliani (8) described three types of acromia. Type I is flat, Type II is curved, and Type III is hooked. A curved or hooked acromion decreases the space available for tendons to glide and they have been associated with impingements symptoms and rotator cuff tears. Outlet impingement may also occur from hypertrophy or calcification of the coracoacromial ligament. Osteophytes at the acromioclavicular joint or at the lateral acromion may cause impingement in these areas (Fig 11-2).

Other Causes of Impingement

In addition to outlet impingement, recent clinical and lab investigations have led to other mechanisms of impingement. These include functional overload, intrinsic tendonopathy, and internal anatomic impingement (9). Functional overload results from excessive strain within the tendon from repetitive overuse or a one-time overload. The subsequent inflammation and tendonitis can lead to a continuous cycle, which leads to further impingement symptoms. Eventually, partial thickness cuff tears may result. These tears can occur within the tendon, or at the tendon-bone interface. The worst case of functional overload is a traumatic complete rotator cuff tear.

Intrinsic tendonopathy or tendonosis is a degenerative process that occurs over time. As such, it is seen more commonly in the elderly (10). Histological studies have shown that with aging, tendon collagen fibers increase in diameter and become less organized (11). Biochemical changes include an increase in collagen, a decrease in mucopolysaccharides and a decrease in water content (12). A lower level

of vascularity is also observed in the aged tendon (13). This combination of loss of cellular integrity and decreased vascularity predisposes the older tendon to an increased incidence of injury.

of vascularity is also observed in the aged tendon (13). This combination of loss of cellular integrity and decreased vascularity predisposes the older tendon to an increased incidence of injury.

It should be noted that the term internal or secondary impingement refers to a different condition. Due to arthroscopy, it has only recently been described as a source of pain and dysfunction (14). Internal impingement occurs in the overhead position with abduction and maximal external rotation (throwing position). In this position the supraspinatus and infraspinatous tendons impinge on the posterior superior aspect of the glenoid labrum (15). In overhead athletes, repetitive internal impingement can lead to labral injury and rotator cuff tears. The cuff tears created by this mechanism are typically partial thickness articular sided tears (16).

At arthroscopy, kissing lesions can often be identified between the superior labrum and undersurface cuff when the arm is placed in abduction and external rotation. Anterior capsular laxity as well as posterior capsular contracture often coexist and can exacerbate the symptoms. When conservative measures fail to improve symptoms, surgical intervention should be considered. Arthroscopic debridement alone has had a success rate of approximately 70 to 80% (17,18,19). Capsular imbrication, either open or arthroscopic, has also been recommended as a treatment to address the anterior capsular laxity. Success for this operation has ranged from 68% (20) to 97% (21). In addition, a tight posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex (PIGHL) has recently been identified as contributing to the pathology. Arthroscopic release of this thickened structure has been shown to be effective in the 10% of patients who do not respond to posterior capsular stretching (22).

Shoulder pain is a common presenting complaint for patients of all ages and activity levels. In clinical frequency it is exceeded only by low back pain and neck pain (23). About 50% of the adult population will have at least one episode of shoulder pain each year (24). The most common source of shoulder pain originates in the subacromial space, with the most prevalent diagnosis being impingement syndrome (25). The spectrum of pathologies includes rotator cuff tendonosis, calcific tendonititis, and subacromial bursitis.

The natural course of subacromial impingement varies somewhat. Long term outcome suggests that it is not self limiting and without treatment, symptoms will persist and usually progress (26). The impingement process has been described as having three chronologic stages (27). Stage 1 is characterized by acute bursitis with subacromial edema and hemorrhage. As the irritation continues, the bursae loses its capability to lubricate and protect the underlying cuff and tendonitis of the rotator cuff develops. This leads to stage II, which is characterized by inflammation and possible partial thickness tears of the rotator cuff. As the process continues the wear on the tendon results in a full thickness tear (stage III). Several authors have shown that this progressive process can be interrupted with surgical acromioplasty (28,29,30).

Patient Presentation

Although impingement symptoms may arise following trauma, the pain more typically develops insidiously over a period of weeks to months (31). The patient’s history will usually consist of pain with overhead activity, reaching, lifting, and throwing. They may have a job or recreational activity that involves repetitive overhead movement (painting, assembly work, tennis). A long day of overhead activity may increase symptoms to the point where the patient seeks medical attention.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree