Essentials of Diagnosis

- When sensorineural hearing loss occurs in the context of an inflammatory condition, it is referred to most appropriately as immune-mediated inner ear disease (IMIED).

- May be associated with disturbances of balance as well as hearing loss because the inner ear mediates vestibular function as well as hearing.

- May occur as a primary inner ear problem or as a complication of a recognized inflammatory condition such as Cogan syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis), giant cell arteritis, Sjögren syndrome, and others.

- Symptoms include tinnitus, vertigo, nausea, and difficulties with two issues related to hearing: acuity and speech discrimination.

General Considerations

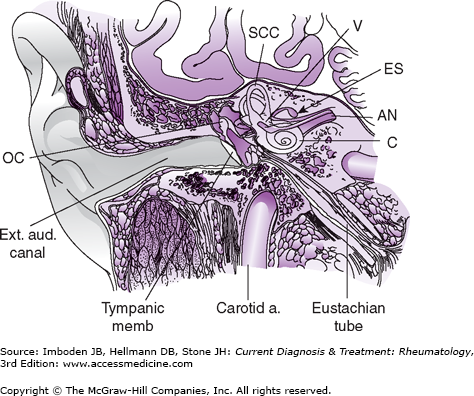

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is an idiopathic inflammatory disorder, either secondary to a known autoimmune disease or occurring as a primary form of disease limited to the ear. The anatomy of the inner ear is shown in Figure 68–1. SNHL is a common feature of some primary forms of vasculitis (eg, Cogan syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis), giant cell arteritis). SNHL also occasionally occurs in association with systemic autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and Sjögren syndrome. Finally, SNHL may represent an organ-specific inflammatory process confined to the inner ear. Injury to the stria vascularis associated with antibody deposition around vessels and vascular occlusion observed in temporal bone specimens is likely to impair the metabolic processes that support hearing transduction. Because hearing loss is often not the sole feature of this syndrome—vertigo, tinnitus, and a sense of aural fullness often occur as well—and because the symptoms respond frequently to immunosuppression, immune-mediated inner ear disease (IMIED) is the preferred term for this disorder when symptoms and signs are confined entirely to the ear. Devastating disabilities including profound deafness and severe vestibular dysfunction are potential sequelae of IMIED. Yet, if diagnosed promptly, IMIED is amenable to treatment. Unfortunately, the prognosis is difficult to gauge except in the setting of profound, sustained SNHL, in which case significant recovery of hearing is unlikely.

Several characteristics distinguish IMIED from other syndromes of inner ear dysfunction. First, its time course is relatively rapid. IMIED is analogous to rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in that inner ear inflammation progresses to severe, irreversible damage within 3 months of onset (and often much more quickly). With IMIED, in fact, the complete loss of hearing within a week or two of symptom onset is not unusual. Second, IMIED is usually bilateral to some degree, albeit the left and right sides may be affected asymmetrically and asynchronously. Typically, weeks or months separate involvement of the two sides, but the interval may be as long as a year or more. Finally, although some cases of IMIED are marked by precipitous, irretrievable losses of inner ear function, others demonstrate fluctuating symptom patterns over a period of several months. Recurrent bouts of SNHL often lead to consistent decrements in hearing capabilities, causing profound hearing deficits in many patients over time.

Clinical Findings

Hearing loss in IMIED may take two forms. First, patients may complain primarily of diminished hearing acuity (the ability to perceive sound). Crude assessments of hearing sensitivity using the mechanical sounds of a watch, the dial-tone of a telephone, or the rubbing of fingers, are inadequate to detect subtle but clinically significant deficits in hearing acuity. Second, patients may also note decreased discrimination (the ability to distinguish individual words). Communication problems arising from poor word discrimination often constitute the chief complaint. Patients with significant deficits in word discrimination are able to hear the sound of a voice on the telephone, but fail to understand what is being said. They also have difficulty participating in conversations conducted amid background noise. Understanding conversations in crowded rooms or restaurants is particularly problematic.

Otoscopy is usually normal in IMIED, even among patients with profound SNHL. In patients with SNHL secondary to granulomatosis with polyangiitis, otoscopy may reveal findings consistent with otitis media caused by granulomatous inflammation within the middle ear cavity, tympanic membrane clouding, or even rupture.

In granulomatosis with polyangiitis, conductive hearing loss caused by middle ear disease is more common than SNHL, but SNHL occurs with a frequency that is probably underrecognized because of failure to obtain audiologic testing in all patients. Conductive hearing loss in granulomatosis with polyangiitis results from a variety of mechanisms, including opacification of the middle ear cleft with fluid or discontinuity of the ossicular ear chain. In contrast, the ischemic sequelae of vasculitis are believed responsible for SNHL. Both vasculitis of the vasa nervorum and compression of the VIIth cranial nerve by granulomatous inflammation as it courses through the middle ear can cause peripheral facial nerve paralysis.

Two simple physical examination tests are useful in distinguishing SNHL from conductive hearing loss: the Weber test and the Rinne test. In the Weber test, a vibrating 512 Hz tuning fork is placed on an upper incisor tooth or mid-forehead. The tone will sound louder in the ipsilateral ear if conductive hearing loss is present, and in the contralateral ear if SNHL is present. The test can be repeated for higher frequencies. In the Rinne test, a vibrating 512 Hz tuning fork is first placed 3 cm from the opening of the ear and then in contact with the mastoid bone. A comparison is made between the loudness of the tone generated in air and that on the bone. A conductive hearing loss of at least 30 dB is suggested when bone conduction exceeds air conduction in loudness. A normal Rinne test (air conduction >bone conduction) in an ear to which the Weber has lateralized, suggests SNHL in that ear.

Otolaryngologists and neurologists, who should become involved in patients’ care if SNHL is suspected, should be expert at evaluating patients’ vestibulo-ocular reflexes (VORs). Other tests, including audiometric testing and electronystagmography, are also essential components of the work-up.

Evaluations of the VORs consist of assessments for nystagmus in response to repetitive head shaking, and for gaze stability during rapid lateral rotation of the head. By detecting head movement, the inner ear provides afferent input to the VOR upon which the central nervous system depends for accuracy in the compensatory saccadic movements of the eyes. Disturbance of the inner ear’s role in maintaining a stable image on the retina leads to a perception of dizziness, which is worsened by head movement and relieved at rest. The rapid changes in afferent input to the central nervous system associated with IMIED lead to VOR decompensation, an inability to maintain a stable retinal image, and a persistent illusion of movement known as vertigo.

The acute phase of vertigo resolves to motion-induced dizziness through central compensation after days to weeks. In the acute phase of vestibular decompensation, spontaneous nystagmus may be seen when visual fixation is suppressed (eg, in the dark or behind Frensel lenses). The VOR can be assessed for each ear separately at the bedside by asking the patient to fix her eyes on the examiner’s nose while the examiner quickly turns the patient’s head 30 degrees toward the ear in question. Normal VORs generate smooth, accurate compensatory ocular saccades. In contrast, abnormal VORs are associated with under- or overshooting of the eye movements, followed by a corrective saccade.

A feeling of perpetual motion known as oscillopsia is a disabling consequence of bilateral VOR loss. The presence of oscillopsia and bilateral vestibular hypofunction can be detected by comparing visual acuity with the Snellen chart while the head is at rest versus during head shaking. A difference in visual acuity of 3 or more lines is an indication of peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Larger decrements are expected in bilateral disease.

Electronystagmography provides objective measure and comparison between ears of peripheral vestibular function, more specifically the lateral semicircular canal. The vestibular electromyographic potential measured in the sternocleidomastoid muscle in response to stimulation of the saccule by low frequency sound assesses another component of peripheral vestibular function.

Cogan syndrome, described in detail in Chapter 42, can be associated with virtually any form of ocular inflammation, including orbital pseudotumor, scleritis, and uveitis. The most characteristic ocular manifestation of Cogan syndrome, however, is interstitial keratitis. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (see Chapter 32) also has a host of potential ocular complications. Diplopia, amaurosis fugax, and anterior ischemic optic neuropathy are common manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Aside from secondary sicca symptoms, the most common eye problem in SLE (see Chapters 21 and 22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree