General Considerations

Vasculitis refers to a heterogeneous group of disorders that is characterized by inflammatory destruction of blood vessels. Inflamed blood vessels are liable to occlude or rupture or develop a thrombus, and thereby lose the ability to deliver oxygen and other nutrients to tissues and organs. Depending on the size, distribution, and severity of the affected vessels, vasculitis can result in clinical syndromes that vary in severity from a minor self-limited rash to a life-threatening multisystem disorder.

Because it often begins with nonspecific symptoms and signs and unfolds slowly over weeks or months, vasculitis is one of the great diagnostic challenges in all of medicine. Yet, physicians who know the general and specific clinical clues for vasculitis can often learn to suspect when vasculitis is present at the bedside. Establishing the diagnosis of vasculitis requires confirmation by laboratory tests, usually a biopsy of an involved artery but sometimes an angiogram or a serologic test.

Classification

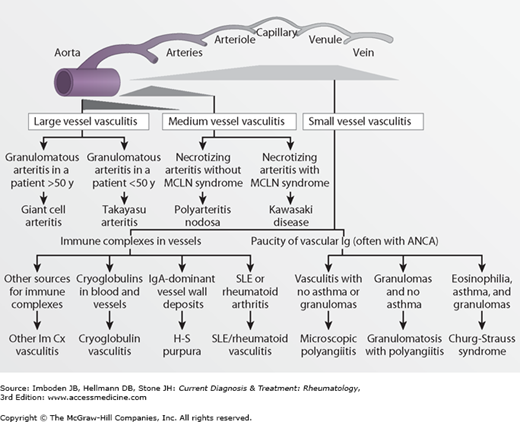

Because the causes of most forms of vasculitis are not known, the vasculitides are classified according to their clinicopathologic features. Although no schema has been accepted universally, one frequently used classification system separates the vasculitides based first on whether the process is primary (ie, of unknown cause) or secondary to some other condition (eg, a connective tissue disease or infection). The vasculitides can then be further separated by the size of vessels usually affected—large-sized, medium-sized, or small-sized arteries (Table 29–1 and Figure 29–1). Finer distinctions among forms of vasculitis affecting the same size vessel can be made by other clinicopathologic characteristics. For example, Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis are grouped together because they both can affect the aorta and other large arteries. However, they are distinguished from each other by their clinical differences, such as the age of onset. Takayasu arteritis is chiefly a disease of young women, while giant cell arteritis almost never occurs before age 50. To take another example, both granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome) affect small-sized vessels and are associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. But only Churg-Strauss syndrome is associated with asthma and striking levels of eosinophilia.

|

Figure 29–1.

Diagram illustrating the vascular distribution of major types of vasculitis. ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; H-S purpura, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; Im Cx, immune complex; MCLN, mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. (Modified, with permission, from Jennette JC, Falk FJ. Nosology of primary vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:10.)

Although classification systems are useful in highlighting differences among the vasculitides, the arbitrary categories suggest neater lines of demarcation than nature always recognizes. Despite being classified as a form of primary, medium-vessel vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa results from chronic hepatitis B or C infection in about 20% of cases and can affect small vessels. Until the causes of all forms of vasculitis are known, exceptions in the classification schema will be common.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of individual forms of vasculitis is covered in the relevant chapters. In general, the vasculitides are relatively uncommon but not rare in Western countries: about 1 out of 2000 adults has some form of vasculitis, and each year vasculitis develops in approximately 1 in 7000 adults. In the United States, the most common forms of primary systemic vasculitis are giant cell arteritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis), and microscopic polyangiitis (Table 29–2).

| Form of Vasculitis | Incidence Per Million |

|---|---|

| Giant cell arteritis | 170a |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) | 4–15 |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | 9 |