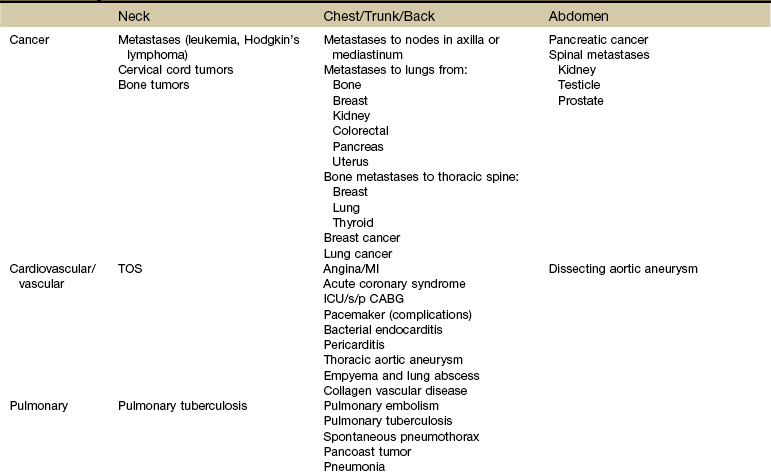

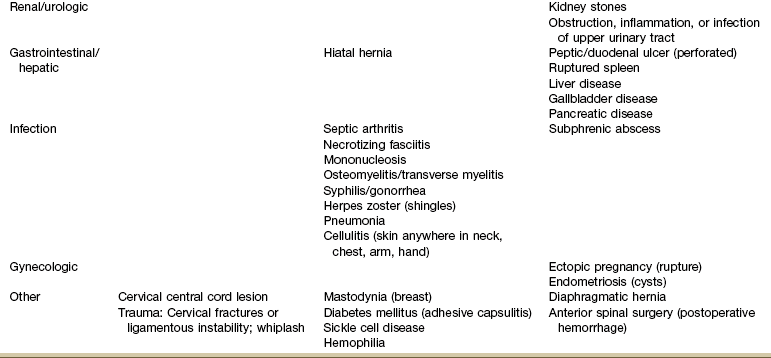

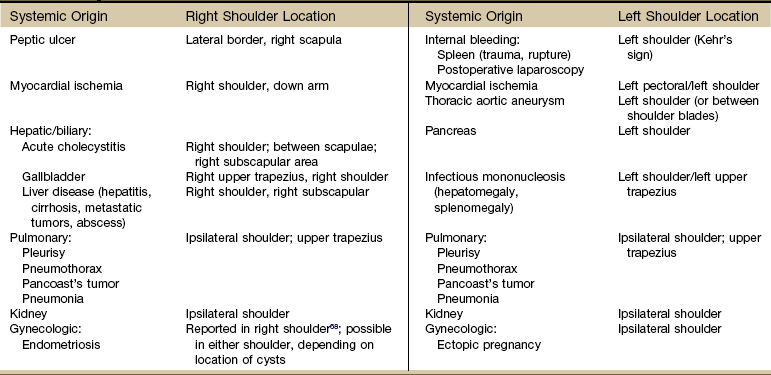

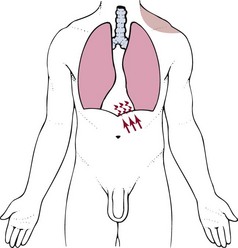

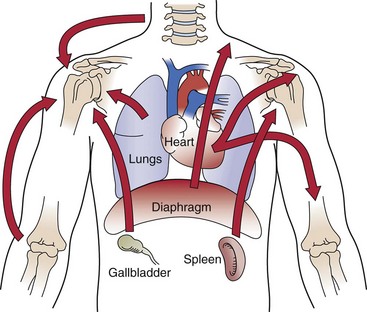

Chapter 18 The therapist is well aware that many primary neuromuscular and musculoskeletal conditions in the neck, cervical spine, axilla, thorax, thoracic spine, and chest wall can refer pain to the shoulder and arm. For this reason, the physical therapist’s examination usually includes assessment above and below the involved joint for referred musculoskeletal pain (Case Example 18-1). Systemic diseases and medical conditions affecting the neck, breast, and any organs in the chest or abdomen can present clinically as shoulder pain (Table 18-1).1 Peptic ulcers, heart disease, ectopic pregnancy, and myocardial ischemia are only a few examples of systemic diseases that can cause shoulder pain and movement dysfunction. Each disorder listed can present clinically as a shoulder problem before ever demonstrating systemic signs and symptoms. As you look over the various potential systemic causes of shoulder symptomatology listed in Table 18-1, think about the most common risk factors and red flag histories you might see with each of these conditions. For example, a history of any kind of cancer is always a red flag. Breast and lung cancer are the two most common types of cancer to metastasize to the shoulder. Heart disease can cause shoulder pain, but it usually occurs in an age specific population.2,3 Anyone over 50 years old, postmenopausal women, and anyone with a positive first generation family history is at increased risk for symptomatic heart disease. Younger individuals may be more likely to demonstrate atypical symptoms such as shoulder pain without chest pain.4 Alternately, although atherosclerosis has been demonstrated in the blood vessels of children, teens, and young adults, they are rarely symptomatic unless some other heart anomaly is present.5,6 Hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia are other red flag histories associated with cardiac-related shoulder pain. Of course, a history of angina,7 heart attack, angiography, stent or pacemaker placement, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), or other cardiac procedure is also a yellow (caution) flag to alert the therapist of the potential need for further screening. Knowledge of risk factors associated with pathologic conditions, illnesses, and diseases helps the therapist navigate the screening process. For example, pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is a possible cause of shoulder pain.8–10 Who is most likely to develop TB? Risk factors include: • Immunocompromised individuals (e.g., transplant recipients, long-term users of immunosuppressants, anyone treated for long-term rheumatoid arthritis [RA], anyone treated with chemotherapy for cancer) • Immigrants from areas where TB is endemic • Malnourished (e.g., eating disorders, alcoholism, drug users, cachexia) In a case like tuberculosis, there will usually be other associated signs and symptoms such as fever, sweats, and cough. When completing a screening examination for a client with shoulder pain of unknown origin or an unusual clinical presentation, the therapist might look at vital signs, auscultate the client, and see what effect increased respiratory movements have on shoulder symptoms (Case Example 18-2). Differential diagnosis of shoulder pain is sometimes especially difficult because any pain that is felt in the shoulder often affects the joint as though the pain were originating in the joint.3 Shoulder pain with any of the components listed in this chapter should be approached as a manifestation of systemic visceral illness, even if shoulder movements exacerbate the pain or if there are objective findings at the shoulder. Many visceral diseases present as unilateral shoulder pain (Table 18-2). Esophageal, pericardial (or other myocardial diseases), aortic dissection, and diaphragmatic irritation from thoracic or abdominal diseases (e.g., upper GI, renal, hepatic/biliary) all can appear as unilateral pain. Adhesive capsulitis, a condition in which both active and passive glenohumeral motions are restricted, can be associated with diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism,11,12 ischemic heart disease, infection, and lung diseases (tuberculosis, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, Pancoast’s tumors) (Case Example 18-3).9,10,13–15 Shoulder pain (unilateral or bilateral) progressing to adhesive capsulitis can occur 6 to 9 months after CABG. Similarly, anyone immobile in the intensive care unit (ICU) or coronary care unit (CCU) can experience loss of shoulder motion resulting in adhesive capsulitis (Case Example 18-4). Clients with pacemakers who have complications and revisions that result in prolonged shoulder immobilization can also develop complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) and/or adhesive capsulitis.16 So, for example, much of what was said about screening the neck and back (Chapter 14) applied to the sacrum, sacroiliac (SI), and pelvis (Chapter 15); buttock, hip, and groin (Chapter 16); and chest, breast, and rib (Chapter 17). Presenting the shoulder last in this text is by design. These principles do apply to the shoulder but beyond that: In Chapter 2, it was stressed that clients who present with no known cause or insidious onset must be screened along with anyone who has a known or assumed cause of symptoms. Whether the client presents with an unknown etiology of injury or impairment or with an assigned cause, always ask yourself these questions: In Chapter 3, we presented three possible mechanisms for referred pain patterns from the viscera to the soma (embryologic development, multisegmental innervations, and direct pressure on the diaphragm). Multisegmental innervations (see Fig. 3-3) and direct pressure on the diaphragm (see Figs. 3-4 and 3-5) are two key mechanisms for referred shoulder pain. Multisegmental Innervations: Because the shoulder is innervated by the same spinal nerves that innervate the diaphragm (C3 to C5), any messages to the spinal cord from the diaphragm can result in referred shoulder pain. The nervous system can only tell what nerves delivered the message. It does not have any way to tell if the message sent along via spinal nerves C3 to C5 came from the shoulder or the diaphragm. So it takes a guess and sends a message back to one or the other. Diaphragmatic Irritation: Irritation of the peritoneal (outside) or pleural (inside) surface of the central diaphragm refers sharp pain to the ipsilateral upper trapezius, neck and/or supraclavicular fossa (Fig. 18-1). Shoulder pain from diaphragmatic irritation usually does not cause anterior shoulder pain. Pain is confined to the suprascapular, upper trapezius, and posterior portions of the shoulder. As you review Fig. 3-4, note how the heart, spleen, kidneys, pancreas (both the body and the tail), and the lungs can put pressure on the diaphragm. This illustration is key to remembering which shoulder can be involved based on organ pathology. For example, the spleen is on the left side of the body so pain from spleen rupture or injury is referred to the left shoulder (called Kehr’s sign) (Case Example 18-5).18 Either shoulder can be involved with renal colic or distention of the renal cap from any kidney disorder, but it is usually an ipsilateral referred pain pattern depending on which kidney is impaired (see Fig. 10-7; again, via pressure on the diaphragm). Bilateral shoulder pain from renal disease would only occur if and when both kidneys are compromised at the same time. Postlaparoscopic shoulder pain (PLSP) frequently occurs after various laparoscopic surgical procedures. During the procedure air is introduced into the peritoneum to expand the area and move the abdominal contents out of the way. The mechanism of PLSP is commonly assumed to be overstretching of the diaphragmatic muscle fibers due to the pressure of a pneumoperitoneum (residual carbon dioxide [CO2] gas after surgery).19 Pressure from distention causes phrenic nerve–mediated referred pain to the shoulder.20 Fig. 18-2 reminds us that shoulder pain can be referred from the neck, back, chest, abdomen, and elbow. During orthopedic assessment, the therapist always checks “above and below” the impaired level for a possible source of referred pain. With this guideline in mind, we know to look for potential musculoskeletal or neuromuscular causes from the cervical and thoracic spine21 and elbow. • Recent history of laparoscopic procedure (risk factor)18,22,23 • Coincident diaphoresis (cardiac) • Associated GI signs and symptoms • Exacerbation by exertion unrelated to shoulder movement (cardiac) Shoulder pain with any of these present should be approached as a manifestation of systemic visceral illness. This is true even if the pain is exacerbated by shoulder movement or if there are objective findings at the shoulder.24 Using the past medical history and assessing for the presence of associated signs and symptoms will alert the therapist to any red flags suggesting a systemic origin of shoulder symptoms. For example, a ruptured ectopic pregnancy with abdominal hemorrhage can produce left shoulder pain (with or without chest pain) in a woman of childbearing age.25–27 The woman is sexually active, and there is usually a history of missed menses or recent unexplained/unexpected bleeding. Pain of cardiac and diaphragmatic origin is often experienced in the shoulder because the heart and diaphragm are supplied by the C5 to C6 spinal segment, and the visceral pain is referred to the corresponding somatic area (see Fig. 3-3). Vital sign and physical assessment including chest auscultation are important screening tools. See Chapter 4 for details. Angina and/or myocardial infarction (MI) can appear as arm and shoulder pain that can be misdiagnosed as arthritis or other musculoskeletal pathologic conditions (see complete discussion in Chapter 6 and see Figs. 6-8 and 6-9). Shoulder pain associated with MI is unaffected by position, breathing, or movement. Because of the well-known association between shoulder pain and angina, cardiac-related shoulder pain may be medically diagnosed without ruling out other causes, such as adhesive capsulitis or supraspinatus tendinitis, when, in fact, the client may have both a cardiac and a musculoskeletal problem (Case Example 18-6). Using a review of symptoms approach and a specific musculoskeletal shoulder examination, the physical therapist can screen to differentiate between a medical pathologic condition and mechanical dysfunction28 (Case Example 18-7).

Screening the Shoulder and Upper Extremity

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate Shoulder and Upper Extremity

Clinical Presentation

The Shoulder Is Unique

Shoulder Pain Patterns

Associated Signs and Symptoms

Screening for Cardiovascular Causes of Shoulder Pain

Angina or Myocardial Infarction

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Screening the Shoulder and Upper Extremity