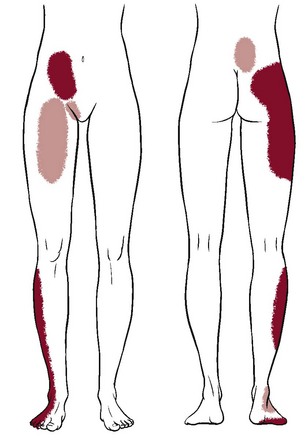

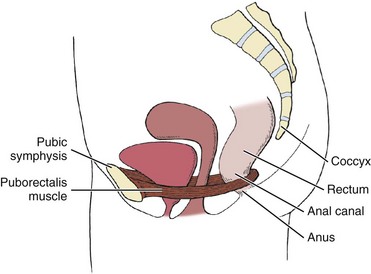

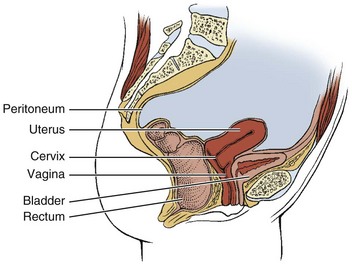

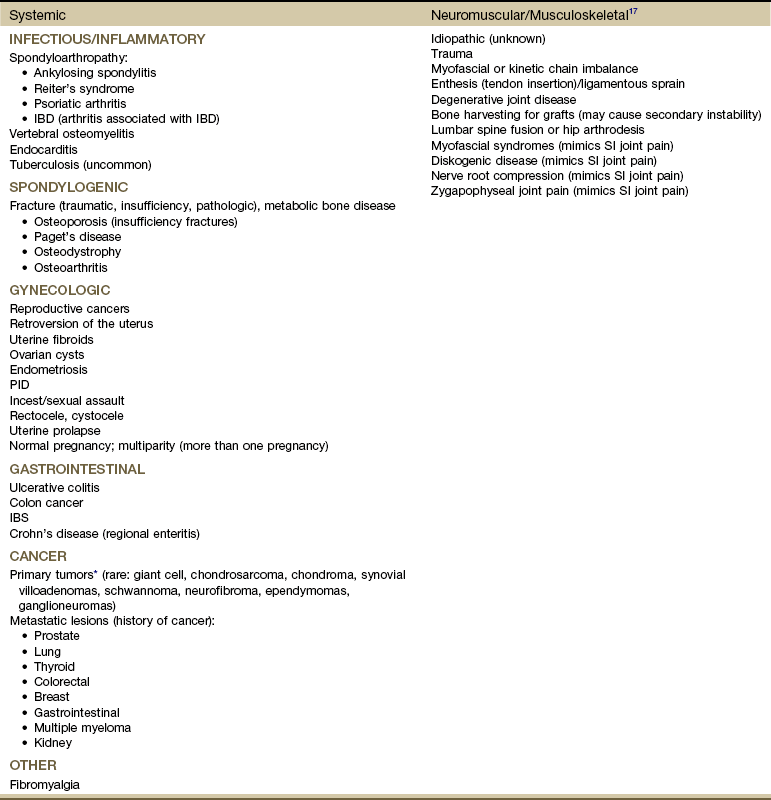

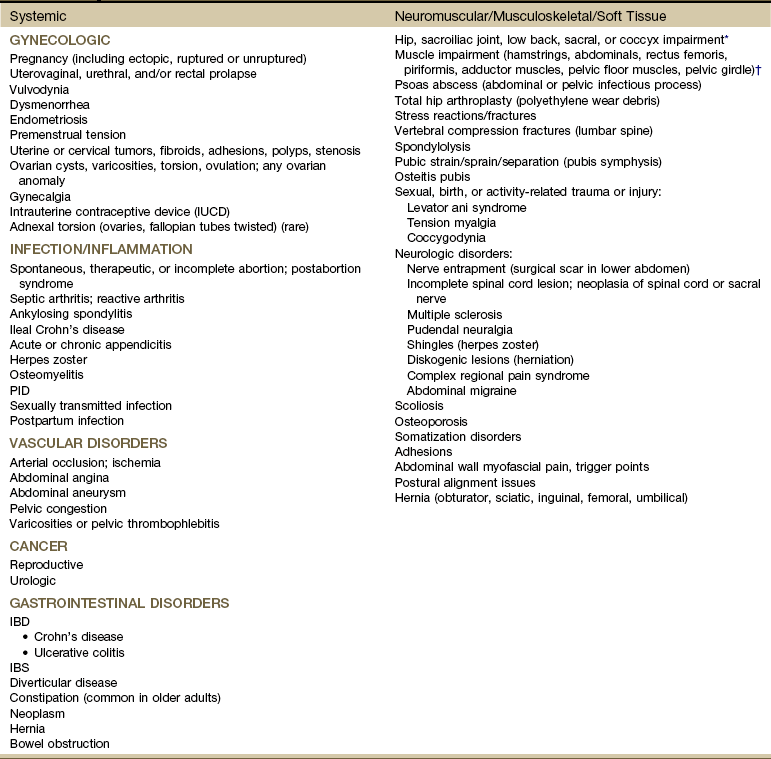

Chapter 15 Following the model for decision making in the screening process outlined in Chapter 1 (see Box 1-7), we now turn our attention to pain from medical conditions, illnesses, and diseases referred to the sacrum, sacroiliac (SI), and pelvic regions. The therapist must be prepared to respond in a professional and responsible way if a man or woman with pelvic or sacral pain reports that he or she has been the victim of repeated violent sexual acts, or if a client admits to physical or emotional assault. More about the client interview, the screening interview, and screening for assault and domestic (intimate partner) violence is included in Chapter 2 (see also Appendices B-3 and B-32). Evaluating the SI joint can be difficult in that no single physical examination finding can predict a disorder of the SI joint. Pain originating from the SI joint can mimic pain referred from lumbar disk herniation, spinal stenosis, facet joint impairment, or even a disorder of the hip.1–3 The most common clinical presentation of sacroiliac pain is associated with a memorable physical event that initiated the pain such as a misstep off a curb, a fall on the hip or buttocks, lifting of a heavy object in a twisted position, or childbirth (Case Example 15-1). A history of previous spine surgery is very common in clients with SI intraarticular pain.1 The most typical medical conditions that refer pain to the sacrum and SI joint include endocarditis, prostate cancer or other neoplasm,4 gynecologic disorders, rheumatic diseases that target the SI area (e.g., spondyloarthropathies such as ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, or psoriatic arthritis), and Paget’s disease (Table 15-1).5 TABLE 15-1 Causes of Sacral and Sacroiliac Pain *Includes benign and malignant osseous and neurogenic tumors affecting the sacrum. Disorders of the large intestine and colon, such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease (regional enteritis), carcinoma of the colon, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), can refer pain to the sacrum when abscess develops or when the rectum is stimulated.6 Likewise, primary SI problems can refer pain to the lower abdomen.7 A medical differential diagnosis may be needed to exclude fracture, infection, or tumor. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum can occur after pelvic radiotherapy for cancer8 and in osteoporotic bone with minimal or unremembered trauma.9 (See further discussion in this chapter on spondylogenic causes of sacral pain.) The principles guiding evaluation of SI joint or sacral pain are consistent with the information presented throughout this text and, in particular, in the chapter on back pain (see Chapter 14). Each of the disorders listed in Table 15-1 usually has its own unique clinical presentation with clues available in the past medical history. The presence of associated signs and symptoms is always a red flag. Most of these conditions have clear red flag clues that come to light if the client is interviewed carefully. Insidious onset or unknown cause is always a red flag. Without a clear cause, the therapist looks for something else in the history or accompanying signs and symptoms. Even with a known or assigned cause, it is important to keep other possibilities in mind and to watch for red flags (Box 15-1). Sacral pain in the absence of a history of trauma or overuse is a clue to the presentation of systemic backache. Low back or sacral pain radiating to the buttock or legs may be vascular. Questions about the effects of activity on symptoms and history of cardiovascular or peripheral vascular diseases are important (see discussion in Chapter 14). Sorting out pain of a vascular versus neurogenic cause is also discussed in Chapter 14. Sacroiliac Joint Pain Pattern: Whether from a mechanical or a systemic origin, the patient usually experiences pain over the posterior SI joint and buttock, with or without lower extremity pain. Pain may be unilateral or bilateral (Fig. 15-1)10 and can be referred to a wide referral zone, including the lumbar spine, abdomen, groin, thigh, foot, and ankle.1,11 Clients with SI joint pain rarely have pain at or above the level of the L5 spinous process, although it is possible. The presence of midline lumbar pain tends to exclude the SI joint as a potential pain generator.12,13 A wide range of SI joint–referred pain patterns occur because innervation is highly variable and complex or because pain may be somatically referred, as discussed in Chapter 3. Adjacent structures, such as the piriformis muscle, sciatic nerve, and L5 nerve root, may be affected by intrinsic joint disease and can become active nociceptors. Pain referral patterns also may be dependent on the distinct location of injury within the SI joint.13,14 SI pain can mimic diskogenic disease with radicular pain down the leg to the foot.15 People who report midline lumbar pain when they rise from a sitting position are likely to have diskogenic pain. Clients with unilateral pain below the level of the L5 spinous process and pain when they rise from sitting are likely to have a painful SI joint.12,13 Pain from SI joint syndrome may be aggravated by sitting or lying on the affected side. Pain gets worse with prolonged driving or riding in a car, weight bearing on the affected side, the Valsalva maneuver, and trunk flexion with the legs straight.14 Risk factors for joint infection include trauma, endocarditis, intravenous drug use, and immunosuppression. Postoperative infection of any kind may not appear with any clinical signs or symptoms for weeks or months. Infections causing bacterial sacroiliitis as a complication of dilatation and curettage (D and C) after incomplete abortions have been reported.16 Infection can cause distention of the anterior joint capsule, irritating the lumbosacral nerve roots.17 Inflammation of the SI joint may result from metabolic, traumatic, or rheumatic causes. Sacroiliitis is present in all individuals with ankylosing spondylitis.18 Reiter’s syndrome (see Chapter 12) occurs most often in young men with venereal disease. Reiter’s syndrome often presents as a triad of symptoms, including arthritis, conjunctivitis, and urethritis. These three symptoms in the presence of sacral pain raise a red flag. The therapist must ask about pain in other joints, urologic symptoms, and a recent (or current) history of conjunctivitis (red, painful inflammation of the eye). A positive sexual history or known diagnosis of venereal disease is helpful information. With sacral or SI pain, the therapist should always consider taking a sexual history (see Special Questions to Ask in Chapter 14 or Appendix B-32). Crohn’s disease (see Chapter 8) may be accompanied by skin rash and joint pain. This enteric condition is well known for its arthritic component, which is present in up to 25% of all cases. The client may have had Crohn’s disease for years and may not recognize the onset of these new symptoms as part of that condition. Skin rash may precede joint pain by days or weeks. The hips, thighs, and legs are affected most often; the rash may be raised or flat, purple or red. Knowing the history and association between skin lesions and joint pain can help the therapist direct screening questions and make a reasonable decision about referral. Metabolic bone disease (MBD) such as osteoporosis, Paget’s disease, and osteodystrophy can result in loss of bone mineral density and deformity or fracture of the sacrum. The therapist should review cases of sacral pain for the presence of risk factors for any of these metabolic bone diseases (see the discussion on metabolic bone disease in Chapter 11). Neoplasm and fracture are two other possible bony causes of sacral pain. Neoplasm is discussed separately in this chapter. Osteoporosis: Osteoporosis can cause insufficiency fractures of the sacrum. The therapist must assess for risk factors (see Boxes 15-2 and 11-3) in anyone with sacral pain, especially those in whom pain has an unknown cause, postmenopausal women, older men (over 65), and anyone with a known history of osteoporosis or Paget’s disease. See further discussion on osteoporosis in Chapter 11 and discussion on fractures at the end of this section. Paget’s Disease: Paget’s disease as a cause of lumbar, sacral, SI, or pelvic pain occurs most commonly in men over 70 years of age (although it can occur earlier and in women). It is the second most common metabolic bone disease after osteoporosis. Characterized by slowly progressive enlargement and deformity of multiple bones, it is associated with unexplained acceleration of bone deposition and resorption. The bones become weak, spongy, and deformed. Redness and warmth may be noted over involved areas, and the most common symptom is bone pain (see further discussion on Paget’s disease in Chapter 11 and an excellent online article as referenced here).19 Three types of fractures affect the sacrum: Traumatic, insufficiency, and pathologic. Trauma resulting in fracture occurs most often with lateral compression injuries seen in motor vehicle accidents or vertical shear injuries resulting from a fall from height onto the lower limbs. Less commonly, direct stress to the sacrum from a fall landing on the buttocks or athletic injury can cause traumatic sacral fracture.20,21 Other risk factors for sacral fracture are listed in Box 15-2. Trauma-related fatigue or stress fracture of the sacrum occurs most often in young active persons and older adults with osteoporosis. Fatigue or stress fractures can develop as a result of submaximal repetitive forces over time such as occur with overuse or overtraining in military personnel and athletes (e.g., runners, volleyball and field hockey players). Less often, pregnant or postpartum women experience sacral stress fractures, especially if they are participating in athletic training activities or running.22–24 Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum result from a normal stress acting on bone with deficient elastic resistance. Reduced bone integrity is most often associated with postmenopausal or corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis and radiation therapy.20 Insufficiency fractures occur insidiously or as a result of minor trauma, possibly even from weight bearing transmitted through the spine.25 Pathologic fracture describes fractures that occur as a result of bone weakened by neoplasm or other disease conditions (e.g., osteomyelitis, giant cell tumor, chordoma, Ewing sarcoma, multiple myeloma). Insufficiency fractures are actually a subset of pathologic fractures confined to bones with structural alterations due to MBD.20 Clinical manifestations of sacral fractures can present with a wide range of signs and symptoms, many of which are present inconsistently and are considered nonspecific.26 Bilateral or multiple stress fractures of the sacrum or pelvis have been reported.27 The client may report or demonstrate localized pain, tenderness with palpation, antalgic gait, and leg length discrepancy. With all sacral fractures, hip, low back, sacral, groin, or buttock pain may occur, especially with multiple stress fractures of the pelvic and sacral bones. Symptoms may mimic other conditions such as disk disease, recurrence of a local tumor, or metastatic disease.20 New onset of sacral or buttock pain 1 to 2 weeks after multilevel lumbosacral fusion with instrumentation should be evaluated for sacral insufficiency fractures, especially if the patient has a recent history of osteoporosis, prolonged sitting, and kyphosis.28–30 See later discussion on gynecologic causes of pelvic pain in this chapter. The therapist is more likely to see clients with referred low back or sacral pain from the small or large intestine as it presents in the low back or sacral area (see Figs. 8-15 and 8-16). Although these illustrations depict the pain in small, very round areas, actual pain patterns can vary quite a bit. The location will be approximately the same, but individual variation does occur. The therapist must ask about the presence of abdominal pain or GI symptoms, occurring either simultaneously or alternating but at the same anatomic level as back or sacral pain. See Case Example 14-13 to review the importance of looking for this particular red flag. MBD to the sacrum from primary breast, lung, colon, and prostate is far more common. Sacral insufficiency fractures after pelvic radiation for rectal, prostate, or reproductive cancers can occur, although these are rare.8,31 Although rare, sacral neoplasms usually are not diagnosed early in the disease course because of mild symptoms resembling low back, buttock, or leg pain (sciatica).32,33 Sacral tumors are not easy to see on x-rays and are easily overlooked due to the curvature of the sacrum, location deep within the pelvis, and frequent presence of overlying bowel gas. It is not uncommon for diagnostic delays as the person is treated for a presumed lumbar pathology before the sacrum is finally identified as the source of pathology.33 Referral to a physical therapist before a correct medical diagnosis is made is not unusual. Giant cell tumor is a highly aggressive local tumor of the bone. The sacrum is the third most common site of involvement. Clients present with localized pain in the lower back and sacrum that may radiate to one or both legs. Swelling may be noted in the involved area. When asked about the presence of other symptoms anywhere in the body, the client may report abdominal complaints and neurologic signs and symptoms (e.g., bowel and bladder or sexual dysfunction, numbness and weakness of the lower extremity).4,34,35 Prostatic (males) or reproductive cancers in men and women can result in sacral pain. See further discussions on testicular cancer in Chapters 10 and 14, prostate cancer in Chapter 10, and gynecologic conditions in this chapter. In the case of persistent coccygodynia with a history of trauma, the therapist must keep in mind the possibility of rectal or bladder lesions (Box 15-3). When asked about the presence of other symptoms, clients with coccygodynia after a traumatic fall may also report bladder, bowel, or sexual symptoms. The therapist must ask whether bladder, bowel, or rectal symptoms were present before the fall. Because 50% of all clients with back or sacral pain from a malignancy have preceding trauma or injury, the apparent trauma (especially if the client reports associated symptoms that were present before the trauma) may be something more serious. For possible clues to treating a client with coccygodynia, the therapist should review Box 15-3, keeping in mind the risk factors for each of these conditions. The therapist should also conduct a neurologic screening examination to identify any signs or symptoms of disk disease. Past history of any of the problems listed is a yellow (warning) flag. Blood in the toilet after a bowel movement may be a sign of anal fissures, hemorrhoids, or colorectal cancer and requires medical evaluation. Once again, the principles used in screening for systemic, medical, or viscerogenic causes of back, sacral, and SI pain also apply to pelvic pain. The history and associated signs and symptoms may vary somewhat according to the cause, but many of the causes are the same (e.g., cancer, GI, vascular, urogenital) (Table 15-2). TABLE 15-2 *The combined medical and physical therapy differential diagnosis includes many origins of pathokinesiologic conditions, including joint laxity; subluxations or displacements; thoracolumbar hypermobility; bursitis; osteoarthritis; spondyloarthropathy; fracture; and postural, ligamentous, or osteoporosis/osteomalacia. (This list is not exhaustive.) †As with joint impairment, the differential diagnosis of muscle pathokinesiologic conditions can include many origins (e.g., trigger points, tendinous avulsion, strain/sprain/tear, weakness, loss of flexibility, pelvic floor overactivity [pain and spasm] or underactivity [laxity, weakness, and leaking], diastasis recti). The most common primary causes of pelvic pain are musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, gynecologic, infectious, vascular, cancer, and GI (in descending order). For example, chronic pelvic pain is most commonly associated with endometriosis, adhesions, IBS, and interstitial cystitis. Infectious disease is the most common systemic cause of pelvic pain.36,37 These two anatomic regions are separated only by walls of muscle. Because the pelvic cavity is in direct communication with the abdominal cavity (see Fig. 14-1), any organ disease or systemic condition of the pelvic or abdominal cavity can cause primary pelvic pain or referred musculoskeletal pain, as is described in this section. Some of the more common red flag histories associated with pelvic pain are listed in Box 15-4. With the use of categories from the screening model, risk factors, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms also are listed. Most conditions that affect the pelvic structures are found in women, but men may also experience pelvic floor impairment and pain. Sexual assault, anal intercourse, prostate or colon cancer, and sexually transmitted disease (STD) are the most common causes for men. Prostate problems such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or prostatitis can cause lower abdominal, back, thigh, or pelvic pain. These conditions are discussed in Chapter 10. In the screening process, clinical presentation and especially pain patterns are very important. Mechanisms of viscerogenic pain (i.e., how these patterns develop) are discussed in Chapter 3. Pelvic floor pain can present suprapubically, perineally, and/or in the low buttock/anal areas. Pelvic girdle pain can occur separately or combined with low back pain and is defined as generally present between the posterior iliac crest (PSIS) and the gluteal fold in the vicinity of the SI joint. Pain may radiate to the posterior thigh; endurance for standing, walking, and sitting is decreased.38 Pelvic girdle pain occurs most often during pregnancy or continues many years postpartum. Many women have both pelvic floor and pelvic girdle pain, requiring each to be addressed externally and internally. Pregnancy-related and postpartum low back pain, pelvic floor pain, and pelvic girdle pain are also common and have an impact on daily life for many women. Prevention and treatment of symptoms is an important issue for therapists who work in the area of women’s health.39,40 Musculoskeletal impairment of the pelvic floor and low back may manifest as dyspareunia (pain before, during, or after intercourse). Overactivity (pain and spasm; muscles contract when they should relax or do not relax completely)41 of the pelvic floor and pelvic floor trigger points can contribute to entrance (superficial or deep) dyspareunia. Deep thrust dyspareunia may also be related to SI or low back impairment. Dyspareunia symptoms that are reduced in alternate positions may indicate a musculoskeletal component, especially when other signs and symptoms characteristic of musculoskeletal impairment are also present.42,43 One of the most common musculoskeletal sources of pelvic floor pain in men and women is the trigger point. Muscles most likely to cause or refer pain to the pelvic area include the levator ani, abdominals, quadratus lumborum, and iliopsoas.44–46 • Aggravated by exercise, weight bearing • Aggravated by trunk/lumbar rotation • Relieved by rest or stretching • Pain or altered movement pattern produced by trunk and lumbar rotation The therapist looks for a contributing history such as a fall on the buttocks, pregnancy, or trauma. Avulsion of hamstrings from a sports injury may be reported. Trauma from physical or sexual assault may remain unreported. Screening for assault is an important part of many evaluations (see Chapter 2). The therapist also looks for muscle impairment. For therapists trained in pelvic floor muscle examination, external and internal palpation of the pelvic floor musculature is helpful.47,48 Examination also includes observation for varicosities and assessment of muscle tone (muscle overactivity [pain and spasm] or underactivity [laxity with weakness and leaking] and the presence of trigger points.44,49,50 Transabdominal ultrasound and vaginal dynamometer are two tools used by some physical therapists to assess pelvic floor muscle contraction. Many clients who experience low back, pelvic, SI, sacral, or groin pain have unrecognized pelvic floor impairment.51 Pain provocation tests for the symphysis pubis and SI joint (e.g., Patrick’s/Faber’s, modified Trendelenburg, Gaenslen’s, shear, P4, gapping, and compression tests), palpation, and mobility testing help point to pelvic girdle impairment, but this could be associated with primary pelvic floor impairment so that both problems coexist.52 The treatment strategy may be to address the pelvic girdle pain first; if it does not resolve, then a pelvic floor muscle examination may be needed to confirm pelvic floor impairment. P4 is a pelvic floor muscle examination that refers to the “provocation of posterior pelvic pain” screening test for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain.52 Reliability and validity of the provocation tests mentioned here have been evaluated and reported; for details see Vleeming38 and Olsen.52 Imaging tests, such as x-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), help rule out problems such as fractures, ankylosing spondylitis, and reactive arthritis.38 Fig. 15-2 gives a simple representation of how the puborectalis muscle acts as a sling around various structures of the pelvis. The condition and position of the pelvic sling are very important in the maintenance of normal pelvic floor health. Fig. 14-1 provides a visual reminder that the muscles of the pelvic floor support the reproductive organs and the viscera in the peritoneum. Any impairment of these organs may cause impairment of the pelvic floor and vice versa. Any weakness or impairment of the pelvic floor can lead to problems with the viscera located in the abdominal or pelvic cavities. Although the underlying pathology differs, symptoms are similar to separation of the symphysis pubis and pelvic ring disruption and may include pain in the involved areas that is aggravated by active motion of the limb or deep pressure and weight bearing during ambulation. Symptoms from pelvic instability as a result of pelvic ring injury or disruption (whether from birth trauma in women of childbearing age or pelvic stress fracture in an older adult with osteoporosis) may be aggravated by single-leg-stance.53,54 Pregnancy, multiparity, and prolonged labor and delivery (especially combined with obesity) are risk factors for gynecologic conditions that can alter the normal position of the bladder, uterus, and rectum in relation to one another (Fig. 15-3), resulting in pelvic organ prolapse such as rectocele, cystocele, and prolapsed uterus with concomitant pelvic floor pain and impairment.

Screening the Sacrum, Sacroiliac, and Pelvis

The Sacrum and Sacroiliac Joint

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate Sacral/Sacroiliac Symptoms

Clinical Presentation

Screening for Infectious/Inflammatory Causes of Sacroiliac Pain

Rheumatic Diseases as a Cause of Sacral or Sacroiliac Pain

Screening for Spondylogenic Causes of Sacral/Sacroiliac Pain

Metabolic Bone Disease

Fracture

Screening for Gynecologic Causes of Sacral Pain

Screening for Gastrointestinal Causes of Sacral/Sacroiliac Pain

Screening for Tumors as a Cause of Sacral/Sacroiliac Pain

The Coccyx

Coccygodynia

The Pelvis

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate the Pelvis

History Associated With Pelvic Pain

Clinical Presentation

Screening for Neuromuscular and Musculoskeletal Causes of Pelvic and Pelvic Floor and Pelvic Girdle Pain

Anterior Pelvic Pain

Screening for Gynecologic Causes of Pelvic Pain

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Screening the Sacrum, Sacroiliac, and Pelvis