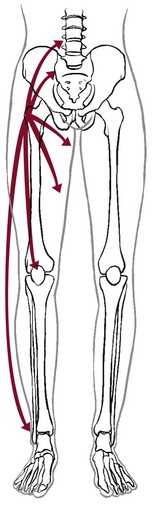

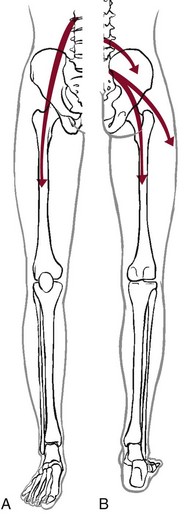

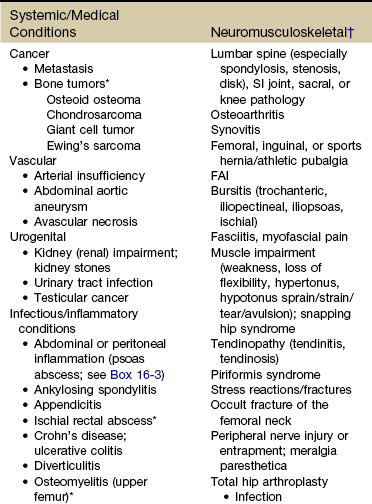

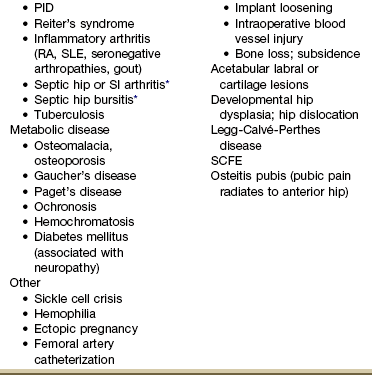

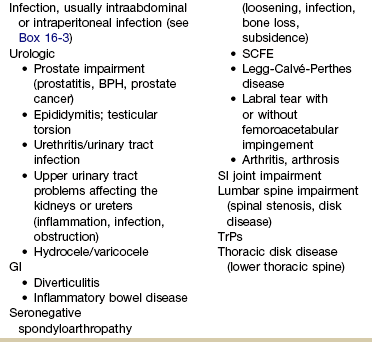

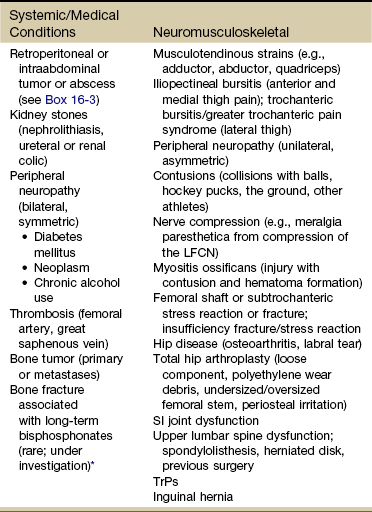

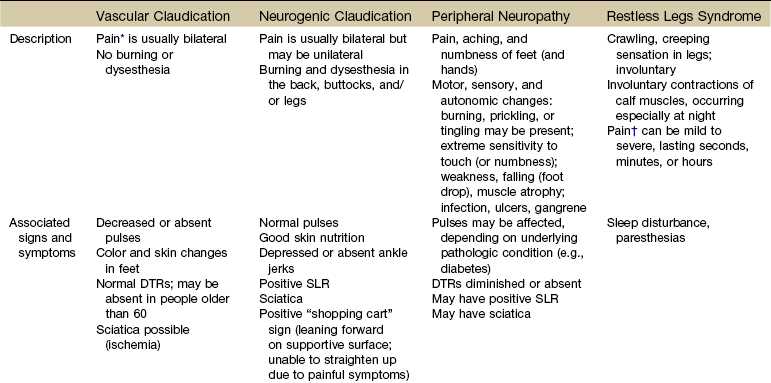

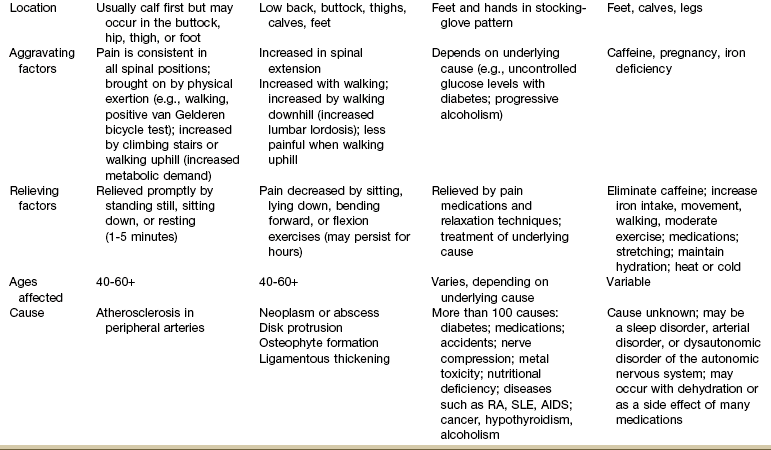

Chapter 16 The causes of lower quadrant pain or dysfunction vary widely; presentation of symptoms is equally wide ranging. Vascular conditions (e.g., arterial insufficiency, abdominal aneurysm), infectious or inflammatory conditions, gastrointestinal (GI) disease, and gynecologic and male reproductive systems may cause symptoms in the lower quadrant and lower extremity,1 including the pelvis, buttock, hip, groin, thigh, and knee. Some overlap may occur, but unique differences exist. Pain may be referred from other locations such as the scrotum, kidneys, abdominal wall, abdomen, peritoneum, or retroperitoneal region. Lower quadrant pain may be referred through conditions that affect nearby anatomic structures, such as the spine, spinal nerve roots, or peripheral nerves, and overlying soft tissue structures (e.g., hernia, bursitis, fasciitis).1a One of the keys to accurate and quick screening is knowledge of the types of conditions, illnesses, and systemic disorders that can refer pain to the lower quadrant, especially the hip and groin. Much of the information related to screening of the back (see Chapter 14), sacrum, sacroiliac (SI), and pelvis (see Chapter 15) also applies to the hip and groin. Some of the more common histories associated with lower extremity, hip, or groin pain of a visceral nature are listed in Box 16-1. A previous history of cancer, such as prostate cancer (men), any reproductive cancers (women), or breast cancer, is a red flag as these cancers may be associated with metastases to the hip. Past history of joint replacement (especially hip arthroplasty) combined with recent infection of any kind and new onset of hip, groin, or knee pain is suspicious. Postoperatively, orthopedic pins may migrate, referring pain from the hip to the back, tibia, or ankle. Loose components, improper implant size, muscular imbalance, and infection that occur any time after joint arthroplasty may cause lower quadrant pain or symptoms (Case Example 16-1). There have been reports of hip, groin, and/or pelvic pain and/or mass associated with wear debris from hip arthroplasty. Polyethylene wear debris can also cause deep vein thrombosis, lower extremity edema, ureteral or bladder compression, or sciatic neuropathy.2 Most known risk factors for systemically induced problems have been discussed in the individual chapters on each specific condition. For example, arterial insufficiency as a cause of low back, hip, buttock, or leg pain is presented as part of the discussion of peripheral vascular disease in Chapter 6 and again in Chapter 14 because it relates just to low back pain. Likewise, known risk factors for bone cancer or metastases as a cause of hip, groin, or lower extremity pain are presented in Chapter 13. Many conditions with overlap symptoms (e.g., back and hip pain, pelvic and groin pain) are presented throughout this third text section (Systemic Origins of Neuromusculoskeletal Pain and Dysfunction) as part of the discussion of back pain (see Chapter 14) or pelvic pain (see Chapter 15). The physical therapist is well acquainted with hip or buttock pain (Table 16-1) as a result of regional neuromuscular or musculoskeletal disorders. The therapist must be aware that disorders affecting the organs within the pelvic and abdominal cavities can also refer pain to the hip region, mimicking a primary musculoskeletal lesion. A careful history and physical examination usually differentiate these entities from true hip disease.4 Pain Pattern: True hip pain, whether from a neuromusculoskeletal or systemic cause (Table 16-2), is usually felt posteriorly deep within the buttock or anteriorly in the groin, sometimes with radiating pain down the anterior thigh. Pain perceived on the outer (lateral) side or posterior aspect of the hip is usually not caused by an intraarticular problem but more likely results from a trigger point, bursitis, knee, SI, or back problem. TABLE 16-2 *Most common causes of the “Sign of the Buttock.” †This is not an exhaustive, all-inclusive list, but rather, it includes the most commonly encountered adult neuromuscular or musculoskeletal causes of hip pain. With true hip joint disease, pain will occur with active or passive motion of the hip joint; this pain increases with weight bearing.5 Often, an antalgic gait pattern is observed as the individual leans away from the affected hip and shortens the swing phase to avoid weight bearing. When the underlying problem is related to soft tissue (e.g., abductor weakness) rather than to the joint as the source of symptoms, the client may lean toward the affected side to compensate for the downward rotation of the pelvis.6 With soft tissue involvement of the bursa or tendons (e.g., gluteus medius, gluteus minimus) pain may radiate from the buttock, greater trochanter, and/or lateral thigh down the leg to the level of insertion of the iliotibial tract on the proximal tibia.7–9 Pain with medial rotation and decreased hip medial range of motion is associated with hip osteoarthritis.10 Cyriax’s “Sign of the Buttock” (Box 16-2) can help differentiate between hip and lumbar spine disease.11–13 The presence of any of these signs may be an indication of osteomyelitis, neoplasm (upper femur, ilium), fracture (sacrum), abscess, or other infection.12 Neuromusculoskeletal Presentation: Identifying the hip as the source of a client’s symptoms may be difficult because pain originating in the hip may not localize to the hip but rather may present as low back, buttock, groin, SI, anterior thigh, or even knee or ankle pain (Fig. 16-1). On the other hand, regional pain from the low back, SI, sacrum, or knee can be referred to the hip. SI pain that localizes to the base of the spine may be accompanied by radicular pain extending across the buttock and down the leg. It can also cross the lateral hip area. Additionally, SI joint dysfunction can cause groin pain and, with referred pain to the hip, may be accompanied by an ipsilateral decrease in hip joint internal rotation of 15 degrees or more, thereby confusing the clinical picture even further.14,15 Hip pain referred from the upper lumbar vertebrae can radiate into the anterior aspect of the thigh, whereas hip pain from the lower lumbar vertebrae and sacrum is usually felt in the gluteal region, with radiation down the back or outer aspect of the thigh (Fig. 16-2). The client with pain caused by component instability following total hip arthroplasty may report hip or groin pain with activity, pain at rest, or both. Clinically, a history of “start up” pain may indicate a loose component. After 5 or 10 steps, the groin pain subsides. Pain may increase again after a moderate amount of walking. Groin or thigh pain is most common with micromotion at the bone–prosthesis interface or other loose component, periosteal irritation, or an undersized femoral stem.16–18 The client reports a dull aching pain in the thigh with no history of systemic illness or recent trauma. Often, the pain is localized to the site of the prosthetic stem tip. The client points to a specific spot along the anterolateral thigh. Pain on initiation of activity that resolves with continued activity should raise suspicion of a loose prosthesis. Persistent pain that is not relieved with rest and continues through the night suggests infection, requiring medical referral.16,19 Systemic Presentation: A noncapsular pattern of restricted hip motion (e.g., limited hip extension, adduction, lateral rotation) may be a sign of pathology other than a joint problem associated with osteoarthritis, potentially a serious underlying disease (Case Example 16-2). The pattern of movement restriction most common with a capsular pattern for the hip is limitation of hip medial rotation, flexion, abduction, and, sometimes, slight limitation of hip extension. Empty end feel can be an indicator of potentially serious disease such as infection or neoplasm. Empty end feel is described as limiting pain before the end range of motion is reached but with no resistance perceived by the examiner.12 Log-rolling of the hip back and forth, though not sensitive, is generally considered to be the most specific examination maneuver for intraarticular hip pathology because it rotates the femoral head back and forth in relation to the acetabulum and capsule, not stressing any of the surrounding extraarticular structures.20 The test does not identify the specific disease present but identifies the source of the symptoms as intraarticular. The presence of GI symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal bloating or cramping) or urologic symptoms (e.g., urinary frequency, nocturia, dysuria, or flank pain) along with hip pain is cause to take a closer look. Palpable reproduction of painful symptoms is generally considered extraarticular.21 Negative radiographs of the hip may not rule out bone lesions. When intervention by the physical therapist does not yield relief of symptoms (or only temporary relief), further imaging studies may be needed. A careful review of risk factors and clinical presentation will guide this decision.22 The physical therapist may see a client with an isolated groin problem, especially in the sports or military populations (Case Example 16-3), but more often, the individual has low back, pelvic, hip, knee, or SI problems with a secondary complaint of groin pain. Possible systemic and/or visceral causes of groin pain are wide ranging, whether appearing as an isolated symptom or in combination with pelvic, hip, low back, or thigh pain (Table 16-3 and Case Example 16-4). TABLE 16-3 *Pubalgia is really a description of painful symptoms of the groin that can be caused by a wide range of muscular, tendinous, osseous, and even visceral structures. This condition may be labeled osteitis pubis when there is articular involvement such as arthritis, articular instability, or other articular lesions involving the pubic symphysis.35 Neuromusculoskeletal Presentation: Neuromuscular or musculoskeletal causes of groin pain should also be considered (Case Example 16-5).23,24 Keep in mind that intraarticular pathology of the hip can manifest as groin pain owing to the innervation of the hip capsule. Extraarticular hip conditions radiate to the lateral or posterior aspects of the hip.25 Groin pain is a common complaint in sports that involve kicking and rapid change of direction (e.g., soccer, hockey). The most common musculoskeletal cause of groin pain is strain of the adductor muscles, most often involving the adductor longus. The history includes a specific trauma, repetitive motion, or injury, which occurs primarily at the junction of the muscle fibers and the extended tendon of origin. Acutely, this injury causes unilateral or bilateral pain during or after activity, with local palpation of the adductor longus origin, and during passive stretching or active contraction; eccentric activation may be even more painful.26,27 Acute injury may be followed in several days by ecchymosis. Chronic groin or inguinal pain in the active athletic, sports, or military groups is often referred to as athletic pubalgia. Athletic pubalgia is sometimes used interchangeably to describe a sports or athletic hernia, which is a tear in the muscles of the inner thigh, lower abdomen, and/or the fascia.28 The term sports hernia may be a bit misleading because experts in this area do not consider this condition the same as a true inguinal or femoral hernia.29 Symptoms associated with athletic pubalgia are often described as deep groin or lower abdominal pain with exertion (usually unilateral). There may be a localized sharp burning sensation in the lower abdomen and/or inguinal region. Symptoms are relieved with rest but aggravated by activity, especially sport-related activities. As the condition progresses, symptoms may radiate to the adductor region, testes (male), and labia (female).30,31 Labral tears of the acetabulum can also cause groin pain. There may be a history of trauma but acetabular labral tears can occur without trauma. The clinical presentation can vary and include night pain, activity-related pain, positive Trendelenburg sign, and positive impingement sign (pain reproduced with hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation). In young, active individuals with a primary complaint of groin pain with or without a history of trauma, the diagnosis of a labral tear should be suspected and investigated further.32 Femoroacetabular impingement presents as groin pain in young adults. Onset is gradual and progressive with intermittent groin pain after prolonged walking, prolonged sitting, or athletic activities that stress the hip. The impingement test (internal hip rotation and adduction while the hip is flexed) is always positive. Referral for a medical orthopedic examination and imaging studies may be warranted.33 Another common problem in the young athlete or long distance runner is osteitis pubis. Repetitive stress of the adductor group can cause inflammation at the musculotendinous attachment on the pubic bone, contributing to sclerosis and bony changes.34 Osteitis pubis with inflammation and sclerosis of the pubic symphysis can cause both acute and chronic groin pain. Individuals affected most often include competitive sports athletes involved in running, leaping and landing with force, repetitive kicking motions, or training on concrete, uneven, or other hard surfaces. Osteitis pubis can also occur as a result of leg length differences, faulty foot and body mechanics, or muscular imbalances and during pregnancy. Tenderness on palpation of the pubic symphysis helps identify this condition.26 Onset of midline pain that radiates to the groin is typical. Pain is reproduced by palpation of the pubis (anterior), passive hip abduction, and resisted hip adduction. Articular lesions involving the pubis symphysis can also lead to pubalgia.35 Insertional injuries of the upper attachment of the rectus abdominis muscle over the anteroinferior pubis (just lateral to the pubic symphysis) can lead to tendinopathy presenting as pubalgia. Without magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), insertional abdominis pathology cannot be differentiated from adductor pathology as the abdominis pubic attachment and the thigh adductor tendon blend to form one unit.35 Chronic, unresolved groin pain in the athletic population also has been linked with altered neuromotor control.36 The therapist may need to evaluate groin pain from a motor control point of view. See further discussion of stress reaction/fractures in the section on Trauma as a Cause of Hip, Groin, or Lower Quadrant Pain in this chapter. Older adults are more likely to experience hip, buttock, or groin pain associated with arthritis, lumbar stenosis, insufficiency fractures, or hip arthroplasty. Arthritis is characterized by radiating pain to the knee, but not below, with decreased hip range of motion. Gait disturbances may be seen as arthritis progresses.17 Insufficiency fracture of the pubic rami can also cause hip/groin pain, resulting in a reluctance to bear weight on the affected side along with an antalgic gait.37 Hip and groin pain secondary to lumbar stenosis can manifest as low back pain that radiates to the lower extremities. The pain begins and gets worse with ambulation. Standing and walking may also increase symptoms when the lumbar spine assumes a more lordotic position and the ligamentum flavus folds in on itself, pinching the foramina closed. The client who has stenosis bends forward or sits to avoid painful symptoms. Clients who have a total hip arthroplasty for hip pain may have continued groin and buttock pain, secondary to sciatica or lumbar spinal stenosis.17 Systemic Presentation: The clinical presentation of groin pain from a systemic source does not vary from musculoskeletally induced groin pain. Once again, the key is to look at the client’s age (e.g., atherosclerotically induced vascular problems in the older adult), past medical history (e.g., previous history of cancer, liver disease, hemophilia), and gender (e.g., ectopic pregnancy, prostate or testicular problems). In addition, asking about the presence of other symptoms and conducting a Review of Systems may help the therapist identify any one of the systemic causes listed in Table 16-3. Once again, we cannot emphasize enough the importance of conducting a thorough physical examination to rule out systemic or viscerogenic disease as the source of thigh pain; client history and lower quadrant screening examination should be performed (see Box 4-16). Anterior thigh pain is more common (Table 16-4), but posterior thigh pain may occur, with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Local anterior or posterior thigh pain of systemic origin generally occurs as a deep aching generated by soft tissue irritation or bone involvement. Radicular pain is usually a sharp, stabbing pain that projects in dermatomal distributions caused by compression of the dorsal nerve roots. TABLE 16-4 SI, Sacroiliac; LFCN, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve; TrPs, trigger points. *Reports of thigh pain and weakness in affected thigh for weeks to months before a low-energy fracture occurs. See Update: Thighbone fractures in women taking bisphosphonate drugs, Harvard Women’s Health Watch 17(7):6-7, 2010; and Abrahamsen B: Subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures in patients treated with alendronate: A register-based national cohort study, J Bone Miner Res 24(6):1095-1102, 2009. Neuromusculoskeletal Presentation: The lower lumbar vertebrae and sacrum can refer pain to the gluteal and hip region, with pain radiating down the posterior or posterolateral thigh. Pain down the lateral aspect of the thigh to the knee may also be caused by inflammation of the tensor fascia lata with iliotibial band syndrome.5 A similar pattern has been reported in association with irritability, injury, or disease of the thoracolumbar transitional segments,38,39 and at least one case of synovial cell sarcoma presenting as iliotibial band syndrome has been reported.40 Anterior thigh pain is commonly disk related, resulting from L3-L4 disk herniation and occurring most often in older clients with a previous history of lumbar spine surgery. The clinical presentation varies among affected individuals, but thigh pain alone is most common (Case Example 16-6). Use of the extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF) technique has been linked with thigh weakness and/or numbness postoperatively as a possible consequence of trauma to the psoas muscle or femoral nerve during the approach. Symptoms are temporary and appear to resolve with soft tissue healing following surgery.41 Back and thigh pain, a positive reverse straight leg raise (SLR) test, and depressed knee reflex are described more often in clients with disk herniation at the L3-L4 level than in clients with L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels.42,43 A positive reverse SLR is defined as pain traveling down the ipsilateral leg when the person is prone and the leg is extended at the hip and the knee. A positive test is caused by tension on the femoral nerve and its roots.44 Objective neurologic findings, such as hyperreflexia or hyporeflexia, decreased sensation to light touch or pinprick, and decreased motor strength, can occur with soft tissue problems such as bursitis. However, clients with true nerve root irritation experience pain extending into the lower leg and foot. Clients with bursitis exhibit a positive “jump” sign when pressure is applied over the greater trochanter; no jump sign is seen with nerve root irritation.7 A common neuromuscular cause of anterior or anterolateral thigh pain is lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) neuralgia. Entrapment or compression of the LFCN causes pain or dysesthesia, or both, in the anterolateral thigh—a condition called meralgia paresthetica. Compression of the LFCN may occur at the level of the L2 and L3 roots through upper lumbar disk herniation or tumor in the second lumbar vertebra. LFCN neuropathy may occur after spine surgery to repair nerve damage that occurred during harvesting of the iliac bone graft or that resulted from pressure on the pelvis from prone positioning or with use of the Relton-Hall frame.45 Other causes of injury to the LFCN include positioning during hip arthroplasty (at risk: obese individuals)46; abnormal posture; chronic muscle spasm; tight-fitting braces, corsets, or pants; and thigh injury.47 For clients with hip arthroplasty, implant loosening, fracture, or subsidence (sinking down into the bone) can cause thigh pain as the first symptom of instability.19 Both passive and active range of motion should be evaluated to assess implant stability. X-rays are needed to look at component position, bone–prosthesis interface, and signs of fracture or infection.16 Systemic Presentation: The pain pattern for anterior thigh pain produced by systemic causes is often the same as that presented for pain resulting from neuromusculoskeletal causes. The therapist must rely on clues from the history and the presence of associated signs and symptoms to help guide the decision-making process. For example, obstruction, infection, inflammation, or compression of the ureters may cause a pattern of low back and flank pain that radiates anteriorly to the ipsilateral lower abdomen and upper thigh. The client usually has a past history of similar problems or additional urologic symptoms such as pain with urination, urinary frequency, low-grade fever, sweats, or blood in the urine. Murphy’s percussion test (see Fig. 4-54) may be positive when the kidney is involved. Retroperitoneal or intraabdominal tumor or abscess may also cause anterior thigh pain. A past history of reproductive or abdominal cancer or the presence of any condition listed in Box 16-3 is a red flag. Thigh pain has been reported as a prodromal symptom of unilateral low-energy subtrochanteric and femoral shaft (diaphyseal) stress reactions and fractures in a small number of people on long-term bisphosphonate therapy.48 Pain in the lower leg is most often caused by injury, inflammation, tumor (malignant or benign), altered peripheral circulation, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), or neurologic impairment (Table 16-5). Assessment of limb pain follows the series of pain-related questions presented in Fig. 3-6. The therapist can use the information in Boxes 4-13 and 4-16 to conduct a screening examination. TABLE 16-5 Symptoms and Differentiation of Leg Pain *“Pain” associated with vascular claudication may also be described as an “aching,” “cramping,” or “tired” feeling. †“Pain” associated with restless legs syndrome may not be painful but may be described as a “frantic,” “unbearable,” or “compelling” need to move the legs. Neuromusculoskeletal Presentation: In addition to screening for medical problems, the therapist must remember to clear the joint above and below the area of symptoms or dysfunction. True knee pain or symptoms are often described as mechanical (local pain and tenderness with locking or giving way of the lower leg) or loading (poorly localized pain with weight bearing). There are many musculoskeletal or neuromuscular conditions well known to the therapist as a potential cause of generalized knee pain, including muscle spasm, strain, or tear; patellofemoral pain syndrome; tendinitis; ligamentous disruption, meniscal tear, or osteochondral lesion; stress fracture49; and nerve entrapment.50,51 Degenerative joint disease of the hip52 or other hip pathology can masquerade as knee pain in adults.53 Neurologic problems, including spinal stenosis, complex regional pain syndrome (Type 1), neurogenic claudication, and lumbar radiculopathy are common disorders that can produce knee pain. Isolated knee pain involving SI dysfunction has also been reported.54 Pain and impaired function from a variety of intraarticular or extraarticular etiologies can also develop following a total knee arthroplasty.55 Client history and clinical examination will help establish the diagnosis. Assessment of trigger points (TrPs) is also essential as pain referral to the knee from TrPs in the lower quadrant is well recognized but sometimes forgotten.56,57 Many therapists over the years have shared with us stories of clients treated for knee pain with a total knee replacement only to discover later (when the knee pain was unchanged) that the problem was really extraarticular (i.e., coming from the back or hip). On the flip side, it is not as likely but is still possible that hip pain can be caused by knee disease. Individual case reports of hip fracture presenting as isolated knee pain have been published58 (Case Example 16-7).

Screening the Lower Quadrant

Buttock, Hip, Groin, Thigh, and Leg

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate the Lower Quadrant

Past Medical History

Risk Factors

Clinical Presentation

Hip and Buttock

Groin

Thigh

Knee and Lower Leg

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree