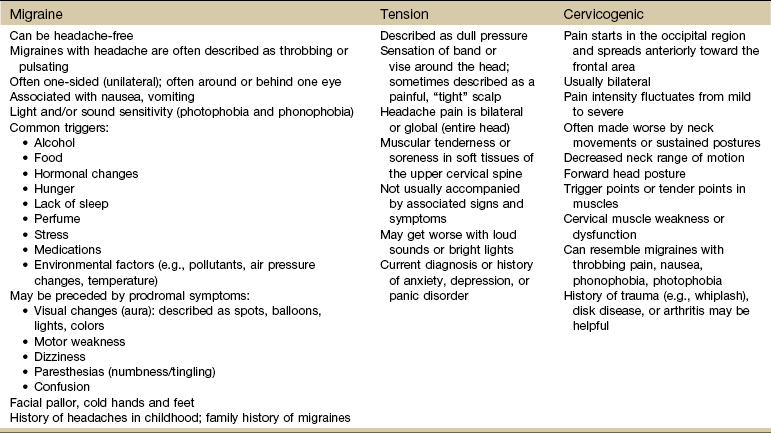

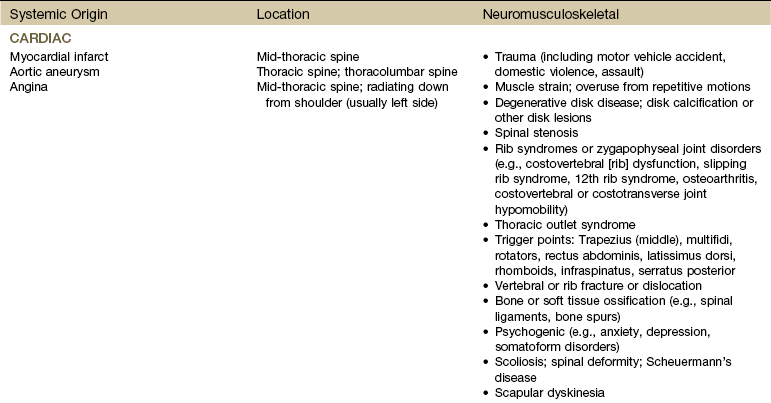

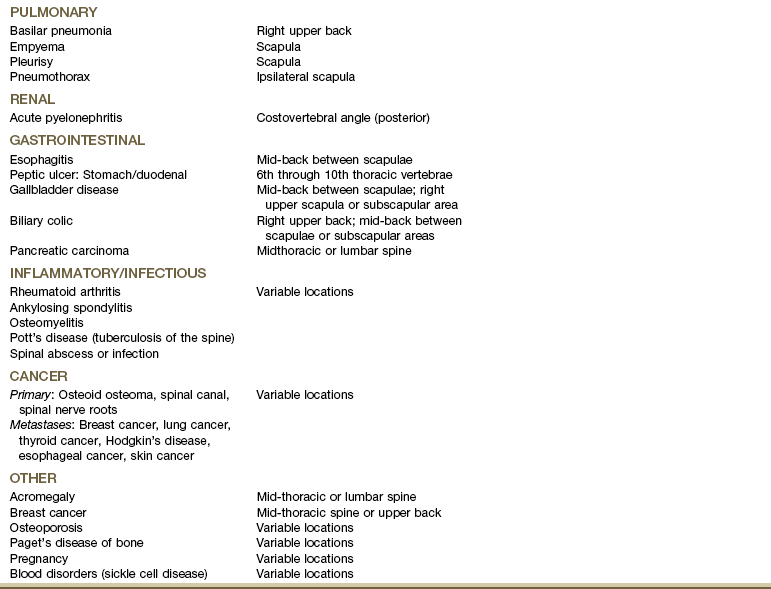

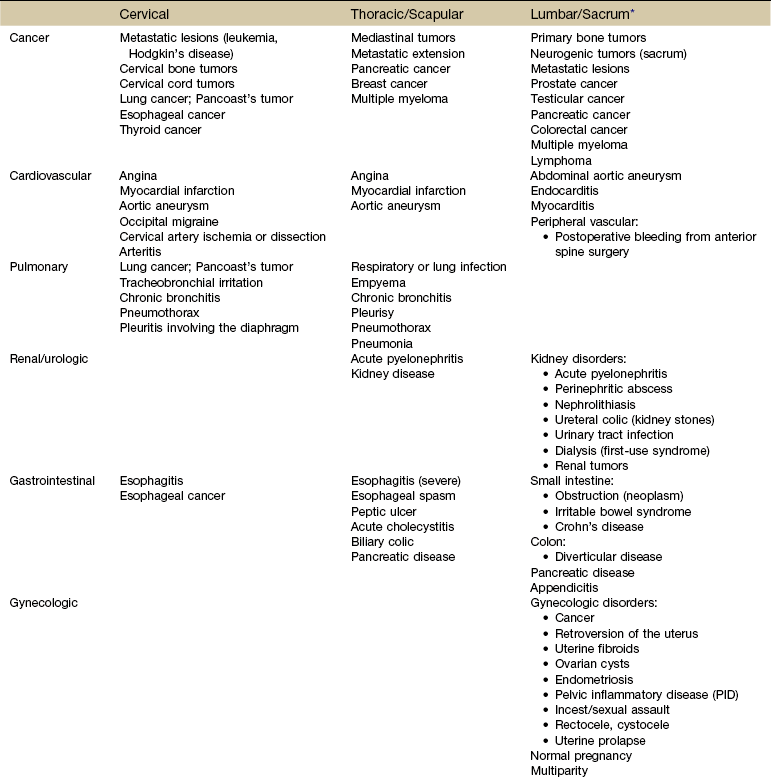

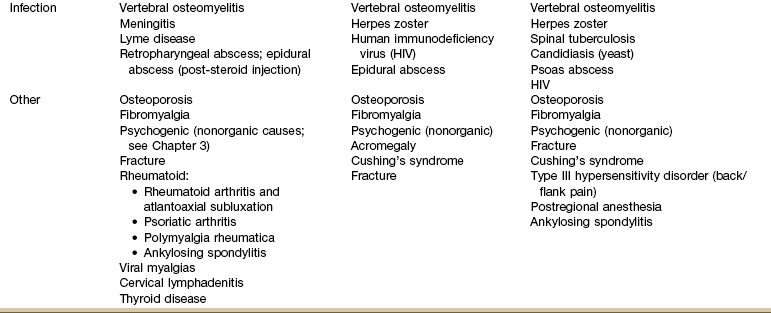

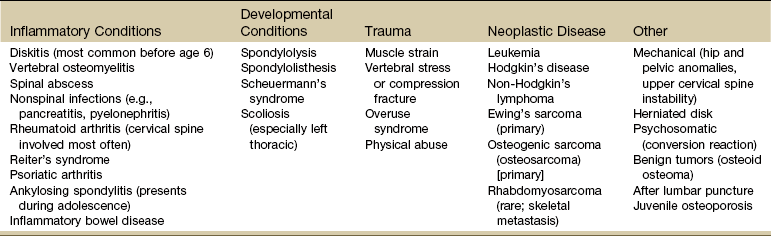

Chapter 14 It is estimated that 80% to 90% of the western population will experience an episode of acute back pain at least once during their lifetime,1 making it one of the most common problems physical therapists evaluate and treat.2–4 It has been suggested that mechanical low back pain (LBP) and leg pain with spinal causes compose approximately 97% of all cases.5 Nonmechanical spinal disease can be attributed to neoplasm, infection, or inflammation in 1% of all cases with another 2% accounted for by visceral disorders (pelvic organs, gastrointestinal [GI] dysfunction, renal involvement, abdominal aneurysms).6 Most cases of back pain in adults are associated with age-related degenerative processes, physical loading, and musculoligamentous injuries. Many mechanical causes of back pain resolve within 1 to 4 weeks without serious problems. It has been estimated that fewer than 2% of individuals presenting with LBP present with significant neurologic involvement or other signs that require referral or imaging.7 Up to 10% of LBP patients have no identifiable cause.8 Sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction can mimic LBP and diskogenic disease with pain referred below the knee to the foot. Studies show SI joint dysfunction is the primary source of LBP in 18% to 30% of people with LBP.8–13 As always, when conducting a physical examination the therapist must consider the possibility of a mechanical problem above or below the area of pain or symptom presentation. A smaller number of people will develop chronic pain without organic pathology or they may have an underlying serious medical condition. The therapist must be aware that many different diseases can appear as neck pain, back pain, or both at the same time (Table 14-1). For example, rheumatoid arthritis affects the cervical spine early in the course of the disease but may go unrecognized at first.14–16 Neck pain may be a feature of any disorder or disease that occurs above the shoulder blades; it is a rare symptom of neoplasm or infection.17 TABLE 14-1 Viscerogenic Causes of Neck and Back Pain *Sacral sources of low back pain (LBP) are discussed separately in Chapter 15. Although the incidence of back pain from NSAIDs is fairly low (i.e., number of people on NSAIDs who develop GI problems and referred pain), the prevalence (number seen in a physical therapist’s practice) is much higher.18–20 In other words physical therapists are seeing a majority of people with arthritis or other inflammatory conditions who are taking one or more prescription and/or over-the-counter (OTC) NSAID.21 Screening for medical disease is an important part of the evaluation process that may take place more than once during an episode of care (see Fig. 1-4). The clues about the quality of pain, the age of the client, and the presence of systemic complaints or associated signs and symptoms indicate the need to investigate further. Watch for history of diabetes, immunosuppression, rheumatologic disorders, tuberculosis, and any recent infection (Case Example 14-1). A history of fever and chills with or without previous infection anywhere in the body may indicate a low-grade infection. The therapist must always ask about a history of motor vehicle accident, blunt impact, repetitive injury, sudden stress caused by lifting or pulling, or trauma of any kind. Even minor falls or lifting when osteoporosis is present can result in severe fracture in older adults (Case Example 14-2). Anyone who cannot bear weight through the legs and hips should be considered for an immediate medical evaluation.21a Surgery of any kind can result in infection and abscess leading to hip, pelvic, abdominal, and/or LBP.22 A recent history of spinal procedures (e.g., fusion, diskectomy, kyphoplasty, vertebroplasty) can be followed by back pain, motor impairment, and/or neurologic deficits when complicated by hematoma, infection, bone cement leakage, or subsidence (graft or instrumentation sinking into the bone).23 Infection following spinal epidural injection is an infrequent but potentially serious complication.24,25 A few key questions to ask about the history might include: Always check medications for potential adverse side effects causing muscular, joint, neck, or back pain. Long-term use of corticosteroids can lead to vertebral compression fractures (Case Example 14-3). Fluoroquinolones (antibiotic) can cause neck, chest, or back pain. Headache is a common side effect of many medications. Keep in mind that physical and sexual abuse are risk factors for chronic head, neck, and back pain for men, women, and children (see Appendix B-3). Age is a risk factor for many systemic, medical, and viscerogenic problems. The risk of certain diseases associated with back pain increases with advancing age (e.g., osteoporosis, aneurysm, myocardial infarction, cancer). Under the age of 20 or over the age of 50 are both red flag ages for serious spinal pathology. The highest likelihood of vertebral fracture occurs in females aged 75 years or older.26 As with all decision-making variables, a single risk factor may or may not be significant and must be viewed in context of the whole patient/client presentation. See Appendix A-2 for a list of some possible health risk factors. Characteristics of pain, such as onset, description, duration, pattern, and aggravating and relieving factors, and associated signs and symptoms are presented in Chapter 3 (see Table 3-2; see also Appendix C-7). Reviewing the comparison in Table 3-2 will assist the therapist in recognizing systemic versus musculoskeletal presentation of signs and symptoms. Other possible associated symptoms may include fatigue, dyspnea, sweating after only minor exertion, and GI symptoms (see also Appendix A-2 for a more complete list of possible associated signs and symptoms). Clusters of these associated signs and symptoms usually accompany the pathologic state of each organ system (see Box 4-19). As part of the physical assessment, the therapist must conduct a Review of Systems. General questions about fevers, excessive weight gain or loss, and appetite loss should be followed by questions related to specific organ systems. Medications should be reviewed for possible adverse side effects. Throughout the interview the therapist must remain alert to any yellow (caution) or red (warning) flags that may signal the need for further screening. Review of Systems is important even for clients who have been examined by a medical doctor. It has been reported that only 5% of physicians assess patients for “red flags.”27,28 In contrast, documentation of red flags by physical therapists (at least for patients with LBP) has been reported as high as 98%.29 Yellow flags are indicators that findings may be present requiring special attention but not necessarily immediate action. One of the primary yellow flag findings that is prognostically important in individuals with LBP is the presence of psychosocial risk factors (e.g., work, attitudes and beliefs, behaviors, affective presentation).31–34 The presence of these yellow flags suggests a poor response to traditional intervention and the need to address the underlying psychosocial aspects of health and healing. A management approach using cognitive behavioral therapy and/or referral to a mental health professional may be warranted.34a,34b Work: In particular, belief that pain is harmful resulting in fear-avoidance behavior and belief that all pain must be gone before going back to work or normal, daily activities contribute to yellow (psychosocial) warning flags. Poor work history, unsupportive work environment, and belief that work is harmful all fall under the category of yellow work flags.30 Beliefs: People with chronic LBP who demonstrate yellow flag beliefs also have an increased risk for poor prognosis. This category includes catastrophizing, thinking the worst, a belief that pain is uncontrollable, poor compliance with exercise, low educational background, and the expectation of a quick fix for pain. Behaviors: Beliefs extend into behaviors such as passive attitude toward rehabilitation, use of extended rest, reduced activity, increased intake of alcohol and other drugs to “manage” the pain, and avoidance or withdrawal from daily and/or social activities. Affective: Depressed mood, irritability, and heightened awareness of bodily sensations along with anxiety represent affective psychosocial yellow flags (also prognostic of poor outcome for chronic LBP). Other affective yellow flags include feeling useless and not needed, disinterest in outside activities, and lack of family or personal support systems. The assessment of psychosocial yellow flags should be part of any ongoing management of LBP at any time in the course of the problem. The New Zealand Guidelines34 recommend the administration of a screening questionnaire at 2 to 4 weeks after onset of pain (see Appendix C-4 for a checklist of red/yellow flag indicators). There is no evidence that this is the optimal time. This is early in the natural history of complaints of LBP, and other interventions may take this long to achieve their effects. In fact, over this time frame, practitioners may still be concerned about red flag conditions, and their time with the client may still be consumed with ensuring compliance with home rehabilitation and analgesics.34 On the other hand, waiting until someone develops chronic pain (3 months) may be too late; the window of opportunity to prevent chronicity will have passed, by definition. Therefore, in anyone with persisting pain, formal exploration of yellow flags should occur no later than 2 months after onset of pain, and possibly by the end of the first month. A practical clinical approach would be to begin screening for yellow flag issues at the 1-month follow-up appointment.35 Watch for the most common red flags associated with back pain of a systemic origin or other medical condition (Box 14-1) but be aware that some recommended red flags have high false-positive rates when used in isolation.36 Each condition (e.g., infection, malignancy, fracture) will likely have its own predictive risk factors. A recent systematic review in the (medical) primary care setting reported that only three red flags are associated with fracture (prolonged use of corticosteroids, age older than 70 years, and significant trauma).36 Individuals with serious spinal pathology almost always have at least one red flag that can be missed when the clinician (physician or therapist) assumes the client’s symptoms are the result of mechanical-induced back pain. (See also Appendix A-2.) Key findings are advancing age, significant recent weight loss, previous malignancy, and constant pain that is not relieved by positional change or rest and is present at night, disturbing the person’s sleep. Poor response to conservative care or poor success with comparable care is an additional red flag in the diagnosis and management of musculoskeletal spine pain.37 According to one source, cancer as a cause of LBP can be ruled out with 100% sensitivity when the affected individual is younger than 50 years old, has no prior history of cancer, no unexplained or unintended weight loss, and responds to conservative care.6 According to a recent systematic review, five red flags have been identified to screen for vertebral fractures in clients presenting with acute LBP including age over 70, female sex, major trauma, pain and tenderness, and a distracting painful injury.38 Older females, especially older adults who have used corticosteroids, are predisposed to osteoporosis and increased risk of fracture from even minor trauma.39,40 More recent evidence to suggest that backache is a frequent finding in children and adolescents and is seldom associated with serious pathology has been published.41–43 But back pain in children is still considered a red flag, especially in young children43a and/or if it has been present for more than 6 weeks because of the concern for infection or neoplasm.43b,43c Children are less likely to report associated signs and symptoms and must be interviewed carefully. Ask about any other joint involvement, swelling anywhere, changes in ROM, and the presence of any constitutional and GI symptoms. A recent history of viral illnesses may be linked to myalgias and diskitis. Most common causes of back pain in children are listed in Table 14-2. TABLE 14-2 Causes of Back Pain in Children From Kliegman RM, editor: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, WB Saunders. Used with permission. Red flags requiring medical evaluation or reevaluation include back pain or symptoms that are not improving as expected, steady pain irrespective of activity, symptoms that are increasing, or the development of new or progressive neurologic deficits such as weakness, sensory loss, reflex changes, bowel or bladder dysfunction, or myelopathy.38 Indications for the use of plain films of the lumbar spine include any of the following features44: Use the Quick Screen Checklist (see Appendix A-1) to conduct a consistent and complete screening examination. A few key screening questions might include: There are many ways to examine and classify head, neck, and back pain. Pain can be divided into anatomic location of symptoms (where is it located?): Cervical, thoracic, scapular, lumbar, and SI joint/sacral (as shown in Table 14-1). For example, intrathoracic disease refers more often to the neck, mid-thoracic spine, shoulder, and upper trapezius areas. Visceral disease of the abdomen and/or pelvis is more likely to refer pain to the low back region. Later in this section, spine pain is presented by the source of symptoms (what is causing the problem?). Whenever faced with the need to screen for medical disease the therapist can review Table 14-1. First identify the location of the pain. Then scan the list for possible causes. Given the client’s history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms, are there any conditions on this list that could be the possible cause of the client’s symptoms? Is age or sex a factor? Is there a positive family or personal history? The brain itself does not feel pain because it has no pain receptors. Most often the headache is caused by an extracranial disorder and is considered “benign.” Headache pain is related to pressure on other structures such as blood vessels, cranial nerves, sinuses, and the membrane surrounding the brain. Serious causes have been reported in 1% to 5% of the total cases, most often attributed to tumors and infections of the central nervous system (CNS).1,46 In the past, headache was viewed as many disorders along a continuum. Better headache classifications have brought about the development of many discrete entities among these disorders.47,48 The International Headache Society (HIS) has published commonly used International Classification of Headache Disorders (second edition, revised), which divides headaches into three parts: primary headache, secondary headache, and cranial neuralgias.49,50 The therapist often provides treatment for secondary headache called cervicogenic headache (CGH). This type of headache is defined as referred pain in any part of the head (e.g., musculoskeletal tissues innervated by these nerve roots) caused by spondylitic, fibrotic, or vascular compression or compromise of cervical nerves (C1-C4).51 CGHs are frequently associated with postural strain or chronic tension, acute whiplash injury, intervertebral disk disease, or progressive facet joint arthritis (e.g., cervical spondylosis, cervical arthrosis) (Table 14-3). Headache can be a symptom of neurologic impairment, hormonal imbalance, neoplasm, side effect of medication,48 or other serious condition (Box 14-2). Headache may be the only symptom of hypertension, cerebral venous thrombosis, or impending stroke.52,53 Sudden, severe headache is a classic symptom of temporal vasculitis (arteritis), a condition that can lead to blindness if not recognized and treated promptly. Recognizing associated signs and symptoms and performing vital sign assessment, especially blood pressure monitoring, are important screening tools for vascular-induced headaches (see Chapter 4 for information on monitoring blood pressure). Stress and inadequate coping are risk factors for persistent headache. Headache can be part of anxiety, depression, panic disorder, and substance abuse.54,55 Headaches have been linked with excessive caffeine consumption or withdrawal in children, adolescents, and adults.56 Therapists often encounter headaches as a complaint in clients with posttraumatic brain injury, postwhiplash injury, or postconcussion injury. A constellation of other symptoms are often present such as dizziness, memory problems, difficulty concentrating, irritability, fatigue, sensitivity to noise, depression, anxiety, and problems with making judgments. Symptoms may resolve in the first 4 to 6 weeks following the injury but can persist for months to years causing permanent disability.57,58 Cancer: The greatest concern is always whether or not there is brain tumor causing the headaches. Only a minority of individuals who have headaches have brain tumors. Risk factors include occupational exposure to gases and chemicals and history of cranial radiation therapy for fungal infection of the scalp or for other types of cancer. A previous history of cancer, even long past history, is a red flag for insidious onset of head and occipital neck pain. Metastatic lesions of the upper cervical spine are difficult to diagnose. Plain radiographs generally appear negative, which can delay diagnosis of clients with C1-C2 metastatic disease.59 Although primary head and neck cancers can cause headaches, neck pain, facial pain, and/or numbness in the face, ear, mouth, and lips are more likely. Other signs and symptoms can include sore throat, dysphagia, a chronic ulcer that does not heal, a lump in the neck, and persistent or unexplained bleeding. Color changes in the mouth known as leukoplakia (white patches) or erythroplakia (red patches) may develop in the oral cavity as a premalignant sign.60 Cancer recurrence is not uncommon within the first 3 years after treatment for cancers of the head and neck; often these cancers are not diagnosed until an advanced stage due to neglect on the part of the affected individual. Cervical spine metastasis is most common with distant metastases to the lungs, although any part of the body can be affected.61 Anyone with a history of head and neck cancer should be screened for cancer recurrence when seen by a therapist for any problem. Tension-type or migraine headaches can occur with tumors. Rapidly growing tumors are more likely to be associated with headache and will eventually present with other signs and symptoms such as visual disturbances, seizures, or personality changes.62,63 Headaches associated with brain tumors occur in up to half of all cases and are usually bioccipital or bifrontal, intermittent, and of increasing duration. Presence of tumor headache varies, depending on size, location, and type of tumor.64 Migraines: Migraine headaches are often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and visual disturbances, but the pain pattern is also often classic in description. Age is a yellow (caution) flag because migraines generally begin in childhood to early adulthood. Migraines can first occur in an individual beyond the age of 50 (especially in perimenopausal or menopausal women); advancing age makes other types of headaches more likely. A family history is usually present, suggesting a genetic predisposition in migraine sufferers. In addition to the typical clinical presentation, there are usually normal examination results. There is a role for the physical therapist because the beneficial effects of exercise on migraine headaches have been documented.65,66 Physical therapy is most effective for the treatment of migraine when combined with other treatments such as biofeedback67 and relaxation training.68 When present, associated signs and symptoms offer the best yellow or red flag warnings. For example, throbbing headache with unexplained diaphoresis and elevated blood pressure may signal a significant cardiovascular event. Daytime sleepiness, morning headache, and reports of snoring may point to obstructive sleep apnea. Headache-associated visual disturbances or facial numbness raises the suspicion of a neurologic origin of symptoms. Other red flags are listed in Box 14-3. The therapist is advised to follow the same screening decision-making model introduced in Chapter 1 (see Box 1-7) and reviewed briefly at the beginning of this chapter. Physical examination should include measurement of vital signs, a general assessment of cardiac and vascular signs, and a thorough head and neck examination. A screening neurologic examination should address mental status (including pain behavior), cranial nerves, motor function, reflexes, sensory systems, coordination, and gait (see Chapter 4). Special Questions to Ask: Headache are listed at the end of this chapter and in Appendix B-17. Traumatic and degenerative conditions of the cervical spine, such as whiplash syndrome and arthritis, are the major primary musculoskeletal causes of neck pain.69 The therapist must always ask about a history of motor vehicle accident or trauma of any kind, including domestic violence. Cervical or neck pain with or without radiating arm pain or symptoms may be caused by a local biomechanical dysfunction (e.g., shoulder impingement, disk degeneration, facet dysfunction) or a medical problem (e.g., infection, tumor, fracture). Referred pain presenting in these areas from a systemic source may occur from infectious disease, such as vertebral osteomyelitis, or from cancer, cardiac, pulmonary, or abdominal disorders (see Table 14-1). Rheumatoid arthritis is often characterized by polyarthritic involvement of the peripheral joints, but the cervical spine is often affected early on (first 2 years) in the course of the disease. Deep aching pain in the occipital, retroorbital, or temporal areas may be present with pain referred to the face, ear, or subocciput from irritation of the C2 nerve root. Some clients may have atlantoaxial (AA) subluxation and report a sensation of the head falling forward during neck flexion or a clunking sensation during neck extension as the AA joint is reduced spontaneously. Symptoms of cervical radiculopathy are common with AA joint involvement.14 Radicular symptoms accompanied by weakness, coordination impairment, gait disturbance, bowel or bladder retention or incontinence, and sexual dysfunction can occur whenever cervical myelopathy occurs, whether from a mechanical or medical cause. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy has been verified as a potential cause of LBP as well.70 The Babinski test may be the most reliable screening test. There is no single reliable or valid clinical screening test or combination of tests that can be used to confirm spinal cord compression myelopathy.71 An imaging study is usually needed to differentiate biomechanical from medical cause of radicular pain, especially when conservative care fails to bring about improvement.72 Torticollis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle may be a sign of underlying thyroid involvement. Anterior neck pain that is worse with swallowing and turning the head from side to side may be present with thyroiditis. Ask about associated signs and symptoms of endocrine disease (e.g., temperature intolerance; hair, nail, skin changes; joint or muscle pain; see Box 4-19) and a previous history of thyroid problems.73 Palpate the anterior spine and have the client swallow during palpation. Palpation of a soft tissue mass or lump should be noted. See guidelines for palpation in Chapter 4. Palpation of a firm, fixed, and immoveable mass raises a red flag of suspicion for neoplasm. Visually inspect and palpate the trachea for lateral deviation to either side.74 Anterior disk bulge into the esophagus or pharynx and/or anterior osteophyte of the vertebral body may give the sensation of difficulty swallowing or feeling a lump in the throat when swallowing. Anxiety can also cause a sensation of difficulty swallowing with a lump in the throat. Conduct a cranial nerve assessment for cranial nerves V and VII (see Table 4-9; see also Appendix B-21). Headache/neck pain may be the early presentation of an underlying vascular pathology. Decreased blood flow to the brain, referred to as cerebral ischemia, may be caused by vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI)/cervical arterial dysfunction75 secondary to atherosclerosis or other arterial dysfunction. Arterial compression can also occur when decreased vertebral height, osteophyte formation, postural changes, and ligamentous changes reduce the foraminal space and encroach on the vertebral artery. Premanipulative screening tests for vertebral artery patency and other tests to “clear” the upper cervical spine before using upper cervical manipulative techniques (e.g., cervical rotation, alar and transverse ligament stress tests, tectorial membrane stress test) may help identify the underlying cause of neck pain. Consensus on the need to conduct these tests has not been reached because the validity of tests for VBI has not been established.76,77 As with the cervical spine and any musculoskeletal part of the body, the therapist must look for the cause of thoracic pain at the level above and below the area of pain and dysfunction. Possible musculoskeletal sources of thoracic pain include muscle strain, vertebral or rib fracture, zygapophyseal joint arthropathy,78 active trigger points, spinal stenosis, costotransverse and costovertebral joint dysfunction, ankylosing spondylitis, intervertebral disk herniation, intercostal neuralgia, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), and T4 syndrome.79 Shoulder impingement and mechanical problems in the cervical spine also can refer pain to the thoracic spine. Systemic origins of musculoskeletal pain in the thoracic spine (Table 14-4) are usually accompanied by constitutional symptoms and other associated symptoms. Often, these additional symptoms develop after the initial onset of back pain, and the client may not relate them to the back pain and therefore may fail to mention them. Tumors occur most often in the thoracic spine because of its length, the proximity to the mediastinum, and direct metastatic extension from lymph nodes with lymphoma, breast, or lung cancer. The client may report symptoms typical of cancer. Tumor involvement in the thoracic spine may produce ischemic damage to the spinal cord or early cord compression since the ratio of canal diameter to cord size is small, resulting in rapid deterioration of neurologic status (Case Example 14-4).

Screening the Head, Neck, and Back

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate the Head, Neck, or Back

Risk Factor Assessment

Clinical Presentation

Associated Signs and Symptoms

Review of Systems

Yellow Flag Findings30

Red Flag Signs and Symptoms

Location of Pain and Symptoms

Head

Causes of Headaches

Cervical Spine

Thoracic Spine

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Screening the Head, Neck, and Back