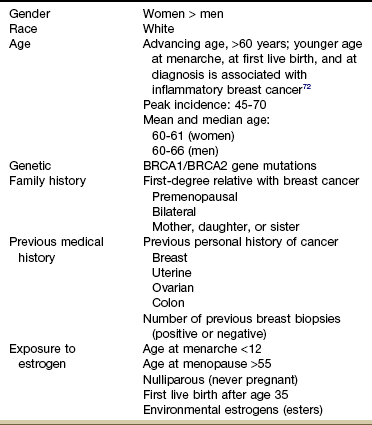

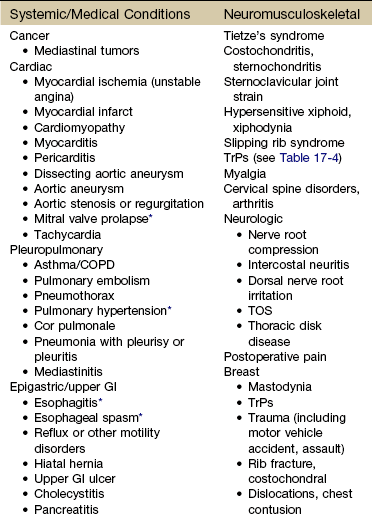

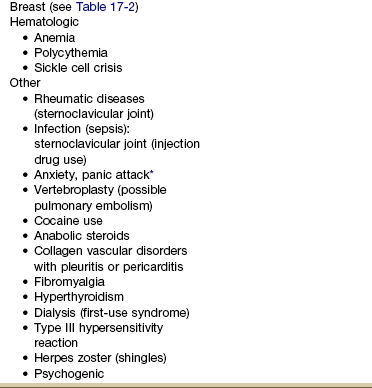

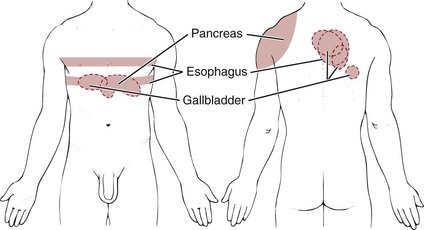

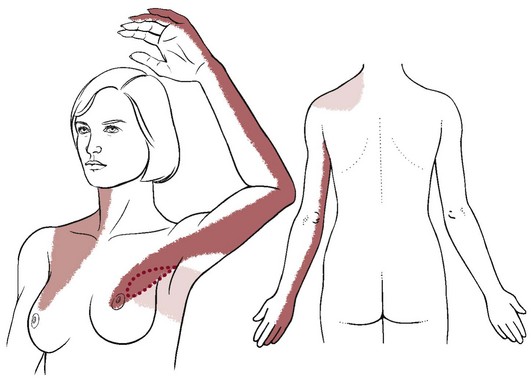

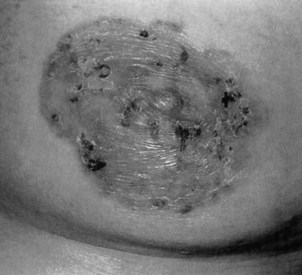

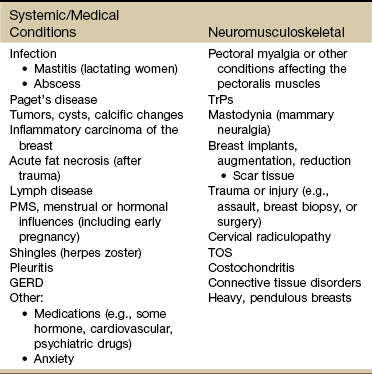

Chapter 17 In other situations, the client reports chest or breast pain as an additional symptom during the screening interview. The pain may occur along with (or alternating with) the presenting symptoms of jaw, neck, upper back, shoulder, breast, or arm pain. When chest pain is the primary complaint, it is often an atypical pain pattern (possibly in a young athlete) that has misled the client and/or the physician.1 On the other hand, it is also possible for clients to have primary chest pain from a human movement system impairment, particularly spinal referred pain.2 Symptoms persist or recur, often with months in between when the client is free of any symptoms. Countless medical tests are performed and repeated with referral to numerous specialists before a physical therapist is consulted (see Case Example 1-7). Finally, so many of today’s aging adults with movement system impairments have multiple medical comorbidities that the therapists must be able to identify signs and symptoms of systemic disease that can mimic neuromuscular or musculoskeletal dysfunction. Systemic or viscerogenic pain or symptoms that can be referred to the chest or breast include the cardiovascular, pulmonary, and upper gastrointestinal (GI) systems, as well as other causes such as cancer, anxiety, steroid use, and cocaine use (Table 17-1).3 Various neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) conditions, such as thoracic outlet syndrome, costochondritis, trigger points, and cervical spine disorders, can also affect the chest and breast.4 The therapist must especially know how and what to look for to screen for cancer, cancer recurrence, and/or the delayed effects of cancer treatment. Cancer can present as primary chest pain with or without accompanying neck, shoulder, and/or upper back pain/symptoms. Basic principles of cancer screening are presented in Chapter 13; specific clues related to the chest, breast, and ribs will be discussed in this chapter. Breast cancer is always a consideration with upper quadrant pain or dysfunction. There are many causes of chest pain, both cardiac and noncardiac in origin (see Table 17-1). Two conditions may be present at the same time, each contributing to chest pain. For example, someone with cervicodorsal arthritis could also experience reflux esophagitis or coronary disease. Either or both of these conditions can contribute to chest pain. Additionally, the woman with chest, breast, axillary, or shoulder pain of unknown origin at presentation must be questioned regarding breast self-examinations. Any recently discovered lumps or nodules must be examined by a physician. The client may need education regarding breast self-examination, and the physical therapist can provide this valuable information.5,6 Techniques of breast self-examination are commonly available in written form for the physical therapist or the client who is unfamiliar with these methods (see Appendix D-6). When the clinical presentation suggests further screening is needed, the therapist can follow the guide to pain assessment (see Chapter 3) and physical assessment for the upper quadrant as presented in Table 4-13. Assess vital signs and watch for trends in heart rate and blood pressure. Keep in mind that tachycardia may be a compensatory response to reduced cardiac output and bradycardia may be an indication of myocardial ischemia or (unreported) trauma. Check to see if the pain can be reproduced or made worse by palpation or with pressure on the chest; and, of course, ask about associated symptoms such as nausea and shortness of breath. The key features that point to spinal referred pain are chest pain reproduced on movement (especially with resistive movement), tenderness and tightness of musculoskeletal structures at a spinal level supplying the painful area, and an absence or lack of symptoms suggestive of a nonmusculoskeletal cause.2 From the previous discussion in Chapter 3, we know that there are at least three possible mechanisms for referred pain patterns to the soma from the viscera (embryologic development, multisegmental innervations, direct pressure on the diaphragm). Pain in the chest may be derived from the chest wall (dermatomes T1-12), the pleura, the trachea and main airways, the mediastinum (including the heart and esophagus), and the abdominal viscera. From an embryologic point of view, the lungs are derived from the same tissue as the gut, so problems can occur in both areas (lung or gut), causing chest pain and other related symptoms. Certain chest pain patterns are more likely to point to a medical rather than musculoskeletal cause. For example, pain that is positional or reproduced by palpation is not as suspicious as pain that radiates to one or both shoulders or arms or that is precipitated by exertion. Physicians agree that the chest pain history by itself is not enough to rule out cardiac or other systemic origin of symptoms. In most cases, some diagnostic testing is needed.7 Parietal pain may appear as unilateral chest pain (rather than midline only) because at any given point the parietal peritoneum obtains innervation from only one side of the nervous system. It is usually not reproduced by palpation. Thoracic disk disease can also present as unilateral chest pain, requiring careful screening.8,9 The four types of pain discussed in Chapter 3 (cutaneous, deep somatic or parietal, visceral, and referred) also apply to the chest. Parietal (somatic) chest pain is the most common systemic chest discomfort encountered in a physical therapy practice. Parietal pain refers to pain generating from the wall of any cavity, such as the chest or pelvic cavity (see Fig. 6-5). Although the visceral pleura are insensitive to pain, the parietal pleura are well supplied with pain nerve endings. It is usually associated with infectious diseases but is also seen in pneumothorax, rib fractures, pulmonary embolism with infarction, and other systemic conditions. There are few nerve endings (if any) in the visceral pleurae (linings of the various organs), such as the heart or lungs. The exception to this statement is in the area of the pericardium (sac enclosed around the entire heart), which is adjacent to the diaphragm (see Fig. 6-5). Extensive disease may develop within the body cavities without the occurrence of pain until the process extends to the parietal pleura. Neuritis (constant irritation of nerve endings) in the parietal pleura then produces the pain described in this section. Cancer can present as primary chest, neck, shoulder, and/or upper back pain and symptoms. A previous history of cancer of any kind is a major red flag (Case Example 17-1). Primary cancer affecting the chest with referred pain to the breast is not as common as cancer metastasized to the pulmonary system with subsequent pulmonary and chest/breast symptoms. The most common symptoms associated with metastases to the pulmonary system are pleural pain, dyspnea, and persistent cough. As with any visceral system, symptoms may not occur until the neoplasm is quite large or invasive because the lining surrounding the lungs has no pain perception. Symptoms first appear when the tumor is large enough to press on other nearby structures or against the chest wall. The presence of any skin changes, lesions, or masses should be documented using the information presented in Box 4-11. Skeletal pain from metastases to the bone or primary cancers such as multiple myeloma affecting the sternum can present much like costochondritis. Ask the client about any recent or current skin changes. Metastatic carcinoma can present with a cellulitic appearance on the anterior chest wall as a result of carcinoma of the lung (see Fig. 4-26). The skin lesion may be flat or raised and any color from brown to red or purple. Liver impairment from cancer or any liver disease can also cause other skin changes, such as angiomas over the chest wall. An angioma is a benign tumor with blood (or lymph, as in lymphangioma) vessels. Spider angioma (also called spider nevus) is a form of telangiectasis, a permanently dilated group of superficial capillaries (or venules; see Fig. 9-3). The primary tumor is usually a lymphoma (Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a young adult or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a child or older adult; see Fig. 4-29), multiple myeloma (primarily observed in people over 60 years of age), or carcinoma of the breast, kidney, or thyroid. When involvement of the chest wall and nerve roots results in pain, the pattern is more diffuse, with radiation of pain to the affected nerve roots (Case Example 17-2). Irritation of an intercostal nerve from rib metastasis produces burning pain that is unilateral and segmental in distribution. Sensory loss or hyperesthesia over the affected dermatomes may be noted. Cardiac-related chest pain may arise secondary to angina, myocardial infarction, pericarditis, endocarditis, mitral valve prolapse, or aortic aneurysm. Despite diagnostic advances, acute coronary syndromes and myocardial infarctions are missed in 2% to 10% of patients.7 There is no single element of chest pain history powerful enough to predict who is or who is not having a coronary-related incident. Medical referral is advised whenever there is any doubt; medical diagnostic testing is almost always required.7 Gender and age are nonmodifiable risk factors for chest pain caused by heart disease. The rate of coronary artery disease (CAD) is rising among women and falling among men. Men develop CAD at a younger age than women, but women make up for it after menopause. Many women know about the risk of breast cancer, but in truth, they are 10 times more likely to die of cardiovascular disease. While one in 30 women’s deaths is from breast cancer, one in 2.5 deaths is from heart disease.10 Women do not seem to do as well as men after taking medications to dissolve blood clots or after undergoing heart-related medical procedures. Of the women who survive a heart attack, 46% will be disabled by heart failure within 6 years.11 African-American women have a 70% higher death rate from CAD compared with Caucasian women.10 Whenever screening individuals who have chest pain, keep in mind that older men and women, menopausal women, and African-American women are at greatest risk for cardiovascular causes. Other risk factors for CAD are listed in Table 6-3. Efforts are being made to determine evidence-based risk factors for low- versus high-risk chest pain of unknown origin. Predictive values for ischemia resulting in myocardial infarction or death include two or more episodes of chest pain typical of a heart attack in an adult 55 years old or older who has a family history of heart disease and/or a personal history of diabetes.12 • Pleuritic pain (exacerbation by deep breathing is more likely pulmonary in nature) • Pain on palpation (musculoskeletal cause) For women, symptoms can be more subtle or atypical (Box 17-1). Chest pain or discomfort is less common in women but still a key feature for some. They often have prodromal symptoms (e.g., pain in the chest, pain in the shoulder or back, radiating pain or numbness in the arms, dyspnea, and fatigue) 12 months prior and up to 1 month before having a heart attack (see Table 6-4).13–15 Black women younger than 50 years are more likely to report frequent and intense prodromal symptoms.16 Chest pain caused by angina is often confused with heartburn or indigestion, hiatal hernia, esophageal spasm, or gallbladder disease, but the pain of these other conditions is not described as sharp or knifelike. The client often says the pain feels like “gas” or “heartburn” or “indigestion.” Referred pain from a trigger point in the external oblique abdominal muscle can cause a sensation of heartburn in the anterior chest wall (see Fig. 17-7). Episodes of stable angina usually develop slowly and last 2 to 5 minutes. Discomfort may radiate to the neck, shoulders, or back (Case Example 17-3). Shortness of breath is common. Symptoms of angina may be similar to the pattern associated with a heart attack. One primary difference is duration. Angina lasts a limited time (a few minutes up to a half hour) and can be relieved by rest or nitroglycerin. When screening for angina, a lack of objective musculoskeletal findings is always a red flag: • Active range of motion (AROM), such as trunk rotation, side bending, or shoulder motions, does not reproduce symptoms. • Resisted motion does not reproduce symptoms (horizontal shoulder abduction/adduction). Pulmonary chest pain usually results from obstruction, restriction, dilation, or distention of the large airways or large pulmonary artery walls. Specific diagnoses include pulmonary artery hypertension, pulmonary embolism, mediastinal emphysema, asthma, pleurisy, pneumonia, and pneumothorax. Pleuropulmonary disorders are discussed in detail in Chapter 7. Mechanical alterations related to the overload of respiratory muscles with chronic asthma can lead to chest pain from musculoskeletal dysfunction and alterations in muscle length and posture.17 GI causes of upper thorax pain are a result of epigastric or upper GI conditions. GERD (“heartburn” or esophagitis) accounts for a significant number of cases of noncardiac chest pain, in the young as well as older adults.3,18–20 Stomach acid or gastric juices from the stomach enter the esophagus, causing irritation to the protective lining of the lower esophagus. Whether the client is experiencing GERD or some other cause of chest pain, there is usually a telltale history or associated signs and symptoms to red flag the case. The GI system has a broad range of referred pain patterns based on embryologic development and multisegmental innervations, as discussed in Chapter 3. Upper GI and pancreatic problems are more likely than lower GI disease to cause chest pain. Chest pain referred from the upper GI tract can radiate from the chest posteriorly to the upper back or interscapular or subscapular regions from T10 to L2 (Fig. 17-1). Epigastric pain is typically characterized by substernal or upper abdominal (just below the xiphoid process) discomfort (see Fig. 17-1). This may occur with radiation posteriorly to the back secondary to long-standing duodenal ulcers. Gastric duodenal peptic ulcer may occasionally cause pain in the lower chest rather than in the upper abdomen. Antacid and food often immediately relieve pain caused by an ulcer. Ulcer pain is not produced by effort and lasts longer than angina pectoris. The therapist will not be able to provoke or eliminate the client’s symptoms. Likewise, physical therapy intervention will not have any long-lasting effects unless the symptoms were caused by trigger points (TrPs). The pain has an abrupt onset, is either steady or intermittent, and is associated with tenderness to palpation in the right upper quadrant. The pain may be referred to the back and right scapular areas. A gallbladder problem can result in a sore tenth rib tip (right side anteriorly) as described in Chapter 9 (Case Example 17-4). Rarely, pain in the left upper quadrant and anterior chest can occur. Occasionally, a client may present with breast pain as the primary complaint, but most often the description is of shoulder or arm or neck or upper back pain. When asked if any symptoms occur elsewhere in the body, the client may mention breast pain (Case Example 17-5). Asking the client about history, risk factors, and the presence of other signs and symptoms is the next step (see Box 4-18). Knowing possible causes of breast pain can help guide the therapist during the screening interview (see Table 17-2). On the flip side, a past history of breast cancer in a client who presents with musculoskeletal symptoms with or without a history of trauma does not always mean cancer metastases. A complete evaluation with advanced imaging may be needed to uncover the true underlying etiology as in the reported case of fibular pain in a patient with a history of breast cancer that turned out to be an incomplete nondisplaced distal fibular stress fracture with no evidence of tumor or mass (Case Example 17-6).21 The typical referral pattern for breast pain is around the chest into the axilla, to the back at the level of the breast, and occasionally into the neck and posterior aspect of the shoulder girdle (Fig. 17-2). The pain may continue along the medial aspect of the ipsilateral arm to the fourth and fifth digits, mimicking pain of the ulnar nerve distribution. There is a wide range of possible causes of breast pain, including both systemic or viscerogenic and NMS etiologies (Table 17-2). Not all conditions are life threatening or even require medical attention. TABLE 17-2 Paget’s disease of the breast is a rare form of ductal carcinoma arising in the ducts near the nipple. The woman experiences itching, redness, and flaking of the nipple with occasional bleeding (Fig. 17-3). Paget’s disease of the breast is not related to Paget’s disease of the bone, except that the same physician (Dr. James Paget, a contemporary of Florence Nightingale, 1877) named both conditions after himself. The breast is the second most common site of cancer in women (the skin is first). Cancer of the breast is second only to lung cancer as a cause of death from cancer among women. Male breast cancer is possible but rare, accounting for 1% of all new cases of breast cancer (2,140 cases in 2011 for men compared with 230,480 for women).22 Risk Factors: Despite the discovery of a breast cancer gene (BRCA-1 and BRCA-2), researchers estimate that only 5% to 10% of breast cancers are a result of inherited genetic susceptibility. Normally, BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 help prevent cancer by making proteins that keep cells from growing abnormally. Inheriting either mutated gene from a parent does increase the risk of breast cancer.23 But a much larger proportion of cases are attributed to other factors, such as advancing age, race, smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, excess alcohol intake, exposure to ionizing radiation, and exposure to estrogens (Table 17-3).24 TABLE 17-3 Factors Associated With Breast Cancer For a more detailed guide to risk factors for breast cancer, see the American Cancer Society’s document, What are the risk factors for breast cancer? Available at http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_2x_what_are_the_risk_factors_for_breast_cancer_5.asp. At the same time, it should be remembered that many women diagnosed with breast cancer have no identified risk factors. More than 70% of breast cancer cases are not explained by established risk factors.23,25 There is no history of breast cancer among female relatives in more than 90% of clients with breast cancer. However, first-degree relatives (mother, daughters, or sisters) of women with breast cancer have two to three times the risk of developing breast cancer than the general female population, and relatives of women with bilateral breast cancer have five times the normal risk.23 The presence of any of these factors may become evident during the interview with the client and should alert the physical therapist to the potential for neuromusculoskeletal complaints from a systemic origin that would require a medical referral. There are several easy-to-use screening tools available. In addition to screening for current risk, clients should be given this information for future use (Box 17-2).

Screening the Chest, Breasts, and Ribs

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate the Chest, Breasts, or Ribs

Clinical Presentation

Chest Pain Patterns

Screening for Oncologic Causes of Chest or Rib Pain

Clinical Presentation

Skin Changes

Palpable Mass

Screening for Cardiovascular Causes of Chest, Breast, or Rib Pain

Risk Factors

Clinical Presentation

Cardiac Pain Patterns

Chest Pain Associated with Angina

Screening for Pleuropulmonary Causes of Chest, Breast, or Rib Pain

Past Medical History

Screening for Gastrointestinal Causes of Chest, Breast, or Rib Pain

Clinical Presentation

Epigastric Pain

Hepatic and Pancreatic Systems

Screening for Breast Conditions that Cause Chest or Breast Pain

Past Medical History

Clinical Presentation

Causes of Breast Pain

Paget’s Disease

Breast Cancer