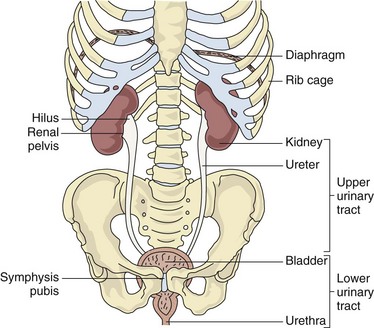

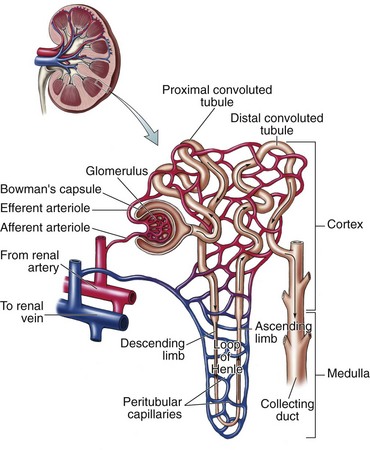

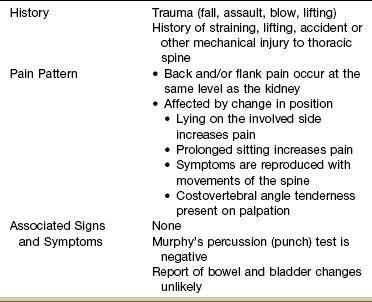

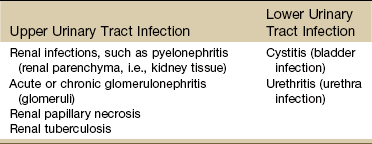

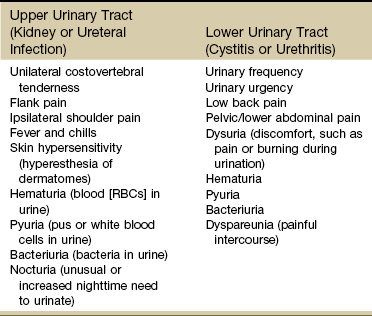

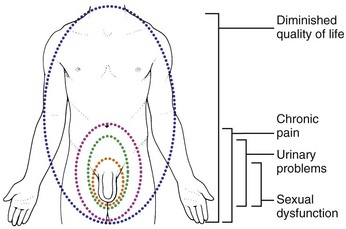

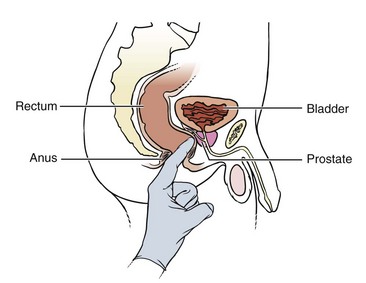

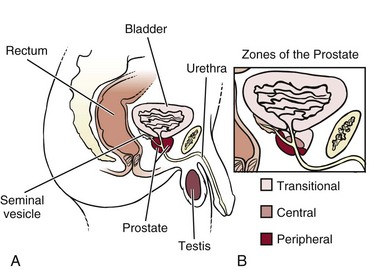

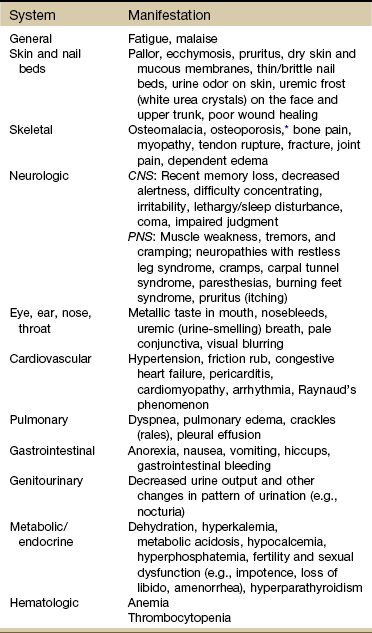

Chapter 10 After further questioning, the client reveals that inspiratory movements do not aggravate the pain, and he has not noticed any change in color, odor, or volume of urine output. However, percussion of the costovertebral angle (see Fig. 4-54) results in the reproduction of the symptoms. This type of symptom complex may suggest renal involvement even without obvious changes in urine. This chapter is intended to guide the physical therapist in understanding the origins and relationships of renal, ureteral, bladder, and urethral symptoms. The urinary tract, consisting of kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra (Fig. 10-1), is an integral component of human functioning that disposes of the body’s toxic waste products and unnecessary fluid and expertly regulates extremely complicated metabolic processes. The ureters, bladder, and urethra function primarily as transport vehicles for urine formed in the kidneys. The lower urinary tract is the last area through which urine is passed in its final form for excretion. Formation and excretion of urine is the primary function of the renal nephron (the functional unit of the kidney) (Fig. 10-2). Through this process the kidney is able to maintain a homeostatic environment in the body. Besides the excretory function of the kidney, which includes the removal of wastes and excessive fluid, the kidney plays an integral role in the balance of various essential body functions, including the following: The failure of the kidney to perform any of these functions results in severe alteration and disruption in homeostasis and signs and symptoms resulting from these dysfunctions (Box 10-1).1 The upper urinary tract consists of the kidneys and ureters. The kidneys are located in the posterior upper abdominal cavity in a space behind the peritoneum (retroperitoneal space) (see Fig. 4-50). Their anatomic position is in front of and on both sides of the vertebral column at the level of T11 to L3. The right kidney is usually lower than the left to accommodate the liver.2 The upper portion of the kidney is in contact with the diaphragm and moves with respiration. The kidneys are protected anteriorly by the ribcage and abdominal organs (see Fig. 4-49) and posteriorly by the large back muscles and ribs. The lower portions of the kidneys and the ureters extend below the ribs and are separated from the abdominal cavity by the peritoneal membrane. The male genital or reproductive system is made up of the testes, epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicles, prostate gland, and penis (Fig. 10-3). These structures are susceptible to inflammatory disorders, neoplasms, and structural defects. Fig. 10-3 A, The prostate is located at the base of the bladder, surrounding a part of the urethra. It is innervated by T11-L1 and S2-S4 and can refer pain to the sacrum, low back, and testes (see Fig. 10-10). As the prostate enlarges, the urethra can become obstructed, interfering with the normal flow of urine. B, The prostate is composed of three zones. The transitional zone surrounds the urethra as it passes through the prostate. This is a common site for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). The central zone is a cone-shaped section that sits behind the transitional zone. The peripheral zone is the largest portion of the gland and borders the other two zones. This is the most common site for cancer development. Most early tumors do not produce any symptoms because the urethra is not in the peripheral zone. It is not until the tumor grows large enough to obstruct the bladder outlet that symptoms develop. Tumors in the transitional zone, which houses the urethra, may cause symptoms sooner than tumors in other zones. Upper Urinary Tract (Renal/Ureteral) Renal sensory innervation is not completely understood, even though the capsule (covering of the kidney) and the lower portions of the collecting system seem to cause pain with stretching (distention) or puncture. Information transmitted by renal and ureteral pain receptors is relayed by sympathetic nerves that enter the spinal cord at T10 to L1 (see Fig. 3-3). Renal pain (see Fig. 10-7) is typically felt in the posterior subcostal and costovertebral regions. To assess the kidney, the test for costovertebral angle tenderness can be included in the objective examination (see Fig. 4-54). Ureteral pain is felt in the groin and genital area (see Fig. 10-8). With either renal pain or ureteral pain, radiation forward around the flank into the lower abdominal quadrant and abdominal muscle spasm with rebound tenderness can occur on the same side as the source of pain. Ureteral obstruction (e.g., from a urinary calculus or “stone” consisting of mineral salts) results in distention of the ureter and causes spasm that produces intermittent or constant severe colicky pain until the stone is passed. Pain of this origin usually starts in the costovertebral angle (CVA) and radiates to the ipsilateral lower abdomen, upper thigh, testis, or labium (see Fig. 10-8). Movement of a stone down a ureter can cause renal colic, an excruciating pain that radiates to the region just described and usually increases in intensity in waves of colic or spasm. Chronic ureteral pain and renal pain tend to be vague, poorly localized, and easily confused with many other problems of abdominal or pelvic origin. There are also areas of referred pain related to renal or ureteral lesions. For example, if the diaphragm becomes irritated because of pressure from a renal lesion, shoulder pain may be felt (see Figs. 3-4 and 3-5). If a lesion of the ureter occurs outside the ureter, pain may occur on movement of the adjacent iliopsoas muscle (see Fig. 8-3). Abdominal rebound tenderness results when the adjacent peritoneum becomes inflamed. Active trigger points along the upper rim of the pubis and the lateral half of the inguinal ligament may lie in the lower internal oblique muscle and possibly in the lower rectus abdominis. These trigger points can cause increased irritation and spasm of the detrusor and urinary sphincter muscles, producing urinary frequency, retention of urine, and groin pain.3 Pseudorenal pain may occur secondary to radiculitis or irritation of the costal nerves caused by mechanical derangements of the costovertebral or costotransverse joints. Disorders of this sort are common in the cervical and thoracic areas, but the most common sites are T10 and T12.4 Irritation of these nerves causes costovertebral pain that can radiate into the ipsilateral lower abdominal quadrant. The onset is usually acute with some type of traumatic history such as lifting a heavy object, sustaining a blow to the costovertebral area, or falling from a height onto the buttocks. The pain is affected by body position, and although the client may be awakened at night when assuming a certain position (e.g., sidelying on the affected side), the pain is usually absent on awakening and increases gradually during the day. It is also aggravated by prolonged periods of sitting, especially when driving on rough roads in the car. It may be relieved by changing to another position (Table 10-1). Fig. 4-54 illustrates percussion over the CVA (Murphy’s percussion or punch test). Although this test is commonly performed, its diagnostic value has never been validated. Results of at least one Finnish study5 suggested that in acute renal colic loin tenderness and hematuria (blood in the urine) are more significant signs than renal tenderness.6 A diagnostic score incorporating independent variables, including results of urinalysis; presence of CVA and renal tenderness; and duration of pain, appetite level, and sex (male versus female), reached a sensitivity of 0.89 in detecting acute renal colic, with a specificity of 0.99 and an efficiency of 0.99.5 Bladder or urethral pain is felt above the pubis (suprapubic) or low in the abdomen (see Fig. 10-9). The sensation is usually characterized as one of urinary urgency, a sensation to void, and dysuria (painful urination). Irritation of the neck of the bladder or the urethra can result in a burning sensation localized to these areas, probably caused by the urethral thermal receptors. See Box 10-2 for causes of pain outside the urogenital system that present like upper or lower urinary tract pain of either an acute or chronic nature. When screening for any conditions affecting the kidney and urinary tract system, keep in mind factors that put people at increased risk for these problems (Case Example 10-1). Early screening and detection is recommended based on the presence of these risk factors.7 • Personal or family history of diabetes or hypertension • Personal or family history of kidney disease, heart attack, or stroke • Personal history of kidney stones, urinary tract infections, lower urinary tract obstruction, or autoimmune disease • African, Hispanic, Pacific Island, or Native American descent • Exposure to chemicals (e.g., paint, glue, degreasing solvents, cleaning solvents), drugs, or environmental conditions Inflammatory disorders of the kidney and urinary tract can be caused by bacterial infection, by changes in immune response, and by toxic agents such as drugs and radiation. Common infections of the urinary tract develop in either the upper or lower urinary tract (Table 10-2). Symptoms of upper urinary tract inflammations and infections are shown in Table 10-3. If the diaphragm is irritated, ipsilateral shoulder pain may occur. Signs and symptoms of renal impairment are also shown in Table 10-4 and if present, are significant symptoms of impending kidney failure. TABLE 10-4 Systemic Manifestations of Chronic Kidney Disease CNS, Central nervous system; PNS, peripheral nervous system. *Bone demineralization leads to a condition called renal osteodystrophy. From Goodman CC, Fuller KS: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2009, WB Saunders. A lower UTI occurs most commonly in women because of the short female urethra and the proximity of the urethra to the vagina and rectum. The rate of occurrence increases with age and sexual activity since intercourse can spread bacteria from the genital area to the urethra. Chronic health problems, such as diabetes mellitus, gout, hypertension, obstructive urinary tract problems, and medical procedures requiring urinary catheterization, are also predisposing risk factors for the development of these infections.8 Individuals with diabetes are prone to complications associated with UTIs. Staphylococcus infection of the urinary tract may be a source of osteomyelitis, an infection of a vertebral body resulting from hematogenous spread or local spread from an abscess into the vertebra. The infected vertebral body may gradually undergo degeneration and destruction, with collapse and formation of a segmental scoliosis.9 Cystitis (inflammation with infection of the bladder), interstitial cystitis (inflammation without infection), and urethritis (inflammation and infection of the urethra) appear with a similar symptom progression (Case Example 10-2). According to the Interstitial Cystitis Association (ICA), interstitial cystitis (IC), also known as painful bladder syndrome, is a condition that consists of recurring pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort in the bladder and pelvic region and affects more than 4 million people in the United States.10 IC is often associated with urinary frequency and urgency. Men can be affected by this condition, but the majority of people living with IC are women. Several other disorders are associated with IC including allergies, inflammatory bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, and vulvitis.11 Bladder pain associated with IC can vary from person to person and even within the same individual and may be dull, achy, or acute and stabbing. Discomfort while urinating also varies from mild stinging to intense burning. Sexual intercourse may ignite pain that lasts for days.11 Clients with any of the symptoms listed for the lower urinary tract in Table 10-3 at presentation should be referred promptly to a physician for further diagnostic workup and possible treatment. Infections of the lower urinary tract are potentially very dangerous because of the possibility of upward spread and resultant damage to renal tissue. Some individuals, however, are asymptomatic, and routine urine culture and microscopic examination are the most reliable methods of detection and diagnosis. Ureteral stones are the ones that cause the most pain. If a stone becomes wedged in the ureter, urine backs up, distending the ureter and causing severe pain. If a stone blocks the flow of urine, urine pressure may build up in the ureter and kidney, causing the kidney to swell (hydronephrosis). Unrecognized hydronephrosis can sometimes cause permanent kidney damage.12 The most characteristic symptom of renal or ureteral stones is sudden, sharp, severe pain. If the pain originates deep in the lumbar area and radiates around the side and down toward the testicle in the male and the bladder in the female, it is termed renal colic. Ureteral colic occurs if the stone becomes trapped in the ureter. Ureteral colic is characterized by radiation of painful symptoms toward the genitalia and thighs (see Fig. 10-8). The nerves that carry pain sensation from the prostate do not localize the source of pain very precisely, and therefore it may be difficult for the man to describe exactly where the pain is coming from. Discomfort can be localized in the suprapubic region or in the penis and testicles, or it can be centered in the perineum or rectum (see Fig. 10-10). Prostatitis: Prostatitis is a relatively common inflammation of the prostate causing prostate enlargement. This condition affects up to 10% of the adult male population, accounting for the 2 million or more men who seek treatment annually in the United States.13,14 It is often disabling, affecting men at any age, but typically found in men ages 40 to 70 years. Acute bacterial prostatitis occurs most often in men under age 35. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Classification of Prostatitis15,16 includes four distinct categories: The symptoms of CP/CPPS appear to occur as a result of interplay between psychologic factors and dysfunction in the immune, neurologic, and endocrine systems.17 Studies show a major impact on quality of life, urinary function, and sexual function along with chronic pain and discomfort (Fig. 10-4).18,19 The pain of prostatitis can be exacerbated by sexual activity, and some men describe pain upon ejaculation. A digital rectal examination by the physician will reproduce painful symptoms when the prostate is inflamed or infected (Fig. 10-5). The NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) provides a valid outcome measure for men with chronic (nonbacterial) prostatitis. The index may be useful in clinical practice, as well as research protocols.20 Anyone with significant symptoms assessed by the NIH-CPSI associated with constitutional symptoms should be rechecked by a physician. Individuals with significant symptoms but no constitutional symptoms and individuals nonresponsive to antibiotics should be assessed by a pelvic floor specialist. The index is available for clinical practice and may be useful for research protocols. It is available online at www.prostatitis.org/symptomindex.html.

Screening for Urogenital Disease

Signs and Symptoms of Renal and Urologic Disorders

The Urinary Tract

Renal and Urologic Pain

Pseudorenal Pain

Lower Urinary Tract (Bladder/Urethra)

Renal and Urinary Tract Problems

Inflammatory/Infectious Disorders

Inflammatory/Infectious Disorders of the Upper Urinary Tract

Inflammatory/Infectious Disorders of the Lower Urinary Tract

Cystitis

Obstructive Disorders

Obstructive Disorders of the Upper Urinary Tract

Obstructive Disorders of the Lower Urinary Tract

Type I

Acute bacterial prostatitis

Type II

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

Type III

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS)

A. Inflammatory

B. Noninflammatory

Type IV

Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis