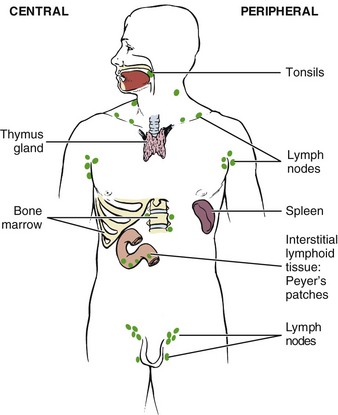

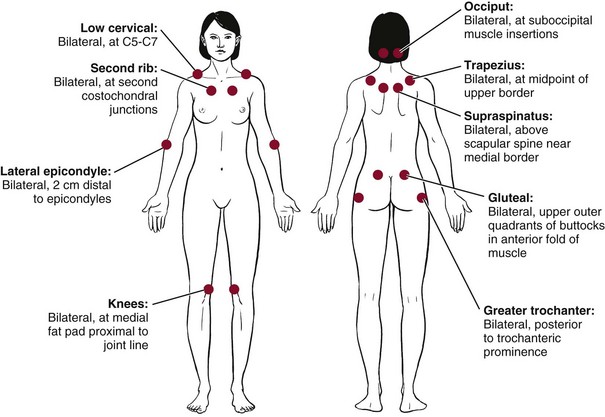

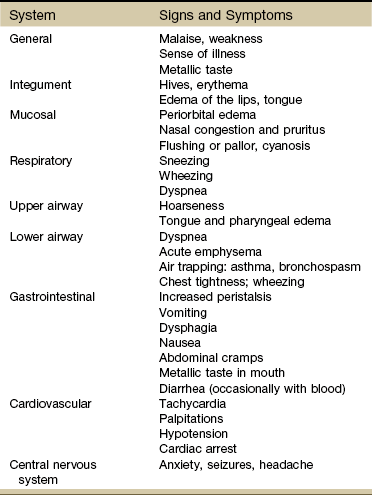

Chapter 12 Immunity denotes protection against infectious organisms. The immune system is a complex network of specialized organs and cells that has evolved to defend the body against attacks by “foreign” invaders. Immunity is provided by lymphoid cells residing in the immune system. This system consists of central and peripheral lymphoid organs (Fig. 12-1). • How long have you had this problem? (acute versus chronic) • Has the problem gone away and then recurred? • Have additional symptoms developed or have other areas become symptomatic over time? The seronegative spondyloarthropathies include a wide range of diseases linked by common characteristics such as inflammatory spine involvement (e.g., sacroiliitis, spondylitis), asymmetric peripheral arthritis, enthesopathy, inflammatory eye disease, and musculoskeletal and cutaneous features. All of these changes occur in the absence of serum rheumatoid factor (RF), which is present in about 85% of people with RA.1 Specific arthropathies have a predilection for involving specific joint areas. For example, involvement of the wrists and proximal small joints of the hands and feet is a typical feature of RA. RA tends to involve joint groups symmetrically, whereas the seronegative spondyloarthropathies tend to be asymmetric. PsA often involves the distal joints of the hands and feet.1 Nail bed changes are especially indicative of underlying inflammatory disease. For example, small infarctions or splinter hemorrhages (see Fig. 4-34) occur in endocarditis and systemic vasculitis. Characteristics of systemic sclerosis and limited scleroderma include atrophy of the fingertips, calcific nodules, digital cyanosis, and sclerodactyly (tightening of the skin). Dystrophic nail changes are characteristic of psoriasis. Spongy synovial thickening or bony hypertrophic changes (Bouchard’s nodes) are present with RA and other hand deformities. With many problems affecting the immune system, taking a step back and reviewing each part of the screening model (history, risk factors, clinical presentation, associated signs and symptoms) may be the only way to identify the source of the underlying problem. Remember to review Box 4-19 during this process. HIV infection is the fifth leading cause of death for people who are between 25 and 44 years old in the United States. Each year, about 2 million people worldwide die of AIDS. African Americans represent about 12% of the total US population but makeup over half of all AIDS cases reported. AIDS is the leading cause of death for African-American men between the ages of 35 and 44. Overall estimates are that 850,000 to 950,000 US residents are living with HIV infection, one-quarter of whom are unaware of their infection. Approximately 56,000 new HIV infections occur each year in the United States, and approximately 2.7 million new HIV cases occur each year worldwide (Box 12-1).2 Risk Factors: Population groups at greatest risk include commercial sex workers (prostitutes) and their clients, men having sex with men, injection drug users (IDUs), blood recipients, dialysis recipients, organ transplant recipients, fetuses of HIV-infected mothers or babies being breast-fed by an HIV-infected mother, and people with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). The latter group is estimated to have a 3 to 5 times higher risk for HIV infection compared with those having no STDs. The rate of new cases of HIV among bisexual men of all races has started to rise again after a period of relative stability. Experts suggest the increase is due to erosion of safe sex practices referred to as prevention fatigue. African Americans (both men and women) are still 8 times as likely as whites to contract HIV, although the rate of newly diagnosed HIV infections among African Americans is slowly declining.3 Transmission: Transmission of HIV occurs according to the following descending hierarchy4: • Both male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use • High-risk heterosexual contact (with someone of the opposite sex with HIV/AIDS or a risk factor for HIV) Transmission occurs through horizontal transmission (from either sexual contact or parenteral exposure to blood and blood products) or through vertical transmission (from HIV-infected mother to infant). HIV is not transmitted through casual contact, such as the shared use of food, towels, cups, razors, or toothbrushes, or even by kissing. Despite substantial advances in the treatment of HIV, the number of new infections has not decreased in the past 10 years. Prevention of infection transmission by reduction of behaviors that might transmit HIV to others is critical.5 Transmission always involves exposure to some body fluid from an infected client. The greatest concentrations of virus have been found in blood, semen, cerebrospinal fluid, and cervical/vaginal secretions. HIV has been found in low concentrations in tears, saliva, and urine, but no cases have been transmitted by these routes. Breast-feeding is a route of HIV transmission from an HIV-infected mother to her infant. The reduction of HIV transmission through breast milk remains a challenge in many resource-poor settings.6,7 Blood and Blood Products: Parenteral transmission occurs when there is direct blood-to-blood contact with a client infected with HIV. This can occur through sharing of contaminated needles and drug paraphernalia (“works”), through transfusion of blood or blood products, by accidental needlestick injury to a health care worker, or from blood exposure to nonintact skin or mucous membranes. Health care workers who have contact with clients with AIDS and who follow routine instructions for self-protection are a very low risk group. The risk for acquiring HIV infection through blood transfusion today is estimated conservatively to be one in 1.5 million, based on 2007-2008 data.8 A blood center in Missouri discovered that blood components from a donation in November 2008 tested positive for HIV infection.9 A subsequent investigation determined that the blood donor had last donated in June 2008, at which time he incorrectly reported no HIV risk factors and his donation tested negative for the presence of HIV. One of the two recipients of blood components from this donation, an individual undergoing kidney transplantation, was found to be HIV infected, and an investigation determined that the recipient’s infection was acquired from the donor’s blood products. The CDC advises that even though such transmissions are rare, health care providers should consider the possibility of transfusion-transmitted HIV in HIV-infected transfusion recipients with no other risk factors.10 Additionally, HIV has been transmitted heterosexually from infected men with hemophilia to spouses or sexual partners in what is termed the second wave of infection and on to children born to infected couples. HIV infection in the United States is currently on the increase among women exposed via sexual intercourse with HIV-infected men. Minority women and women over the age of 50 are being affected more frequently than in prior years.11 Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Many individuals with HIV infection remain asymptomatic for years, with a mean time of approximately 10 years between exposure and development of AIDS. Systemic complaints, such as weight loss, fevers, and night sweats, are common. Cough or shortness of breath may occur with HIV-related pulmonary disease. GI complaints include changes in bowel function, especially diarrhea. Bone disorders such as osteopenia, osteoporosis, and osteonecrosis have been reported in association with HIV, but the etiology and mechanism of these disorders are unknown. Prevalence reported varies from study to study; scientists are researching the influence of antiretroviral therapy and lipodystrophy (absence or presence), severity of HIV disease, and overlapping risk factors for bone loss (e.g., smoking and alcohol intake). The therapist should conduct a risk factor assessment for bone loss in anyone with known HIV and educate clients about prevention strategies.12 Side Effects of Medication: The therapist should review the potential side effects from medication used in the treatment of AIDS. Delayed toxicity with long-term treatment for HIV-1 infection with antiretroviral therapy occurs in a substantial number of affected individuals.13–15 The more commonly occurring symptoms include rash, nausea, headaches, dizziness, muscle pain, weakness, fatigue, and insomnia. Hepatotoxicity is a common complication; the therapist should be alert for carpal tunnel syndrome, liver palms, asterixis, and other signs of liver impairment (see Chapter 9). Body fat redistribution to the abdomen, upper body, and breasts occurs as part of a condition called lipodystrophy associated with antiretroviral therapy. Other metabolic abnormalities, such as dysregulation of glucose metabolism (e.g., insulin resistance, diabetes), combined with lipodystrophy are labeled lipodystrophic syndrome (LDS). LDS contributes to problems with body image and increases the risk for cardiovascular complications.16–19 This has proved to be the case, particularly for TB and certain sexually transmitted infections such as syphilis and the genital herpes virus. Cancer has been linked with AIDS since 1981; this link was discovered with the increased appearance of a highly unusual malignancy, Kaposi’s sarcoma. Since then, HIV infection has been associated with other malignancies, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), AIDS-related primary central nervous system lymphoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma.20–22 Kaposi’s Sarcoma: Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) was first recognized as a malignant tumor of the inner walls of the heart, veins, and arteries in 1873 in Vienna, Austria. Before the AIDS epidemic, KS was a rare tumor that primarily affected older people of Mediterranean and Jewish origin. Clinically, KS in HIV-infected immunodeficient persons occurs more often as purplish-red lesions of the feet, trunk, and head (Fig. 12-2). The lesion is not painful or contagious. It can be flat or raised and over time frequently progresses to a nodule. The mouth and many internal organs (especially those of the GI and respiratory tracts) may be involved either symptomatically or subclinically. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Approximately 3% of AIDS diagnoses in all risk groups and in all areas originate through discovery of NHL. The incidence of NHL increases with age and as the immune system weakens. Tuberculosis: Tuberculosis (TB) was considered a stable, endemic health problem, but now, in association with the HIV/AIDS pandemic, TB is resurgent.23 The recent emergence of multiple-drug–resistant TB, which has reached epidemic proportions in New York City, has created a serious and growing threat to the capacity of TB control programs (see Chapter 7). Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Pulmonary TB is the most common manifestation of TB disease in HIV-positive clients. When TB precedes the diagnosis of AIDS, disease is usually confined to the lung, whereas when TB is diagnosed after the onset of AIDS, the majority of clients also have extrapulmonary TB, most commonly involving the bone marrow or lymph nodes. Fever, night sweats, wasting, cough, and dyspnea occur in the majority of clients (see further discussion of TB in Chapter 7). HIV Neurologic Disease: HIV neurologic disease may be the presenting symptom of HIV infection and can involve the central and peripheral nervous systems. HIV is a neurotropic virus and can affect neurologic tissues from the initial stages of infection. In the early course of the infection, the virus can cause demyelination of central and peripheral nervous system tissues.24 Signs and symptoms range from mild sensory polyneuropathy to seizures, hemiparesis, paraplegia, and dementia. Central Nervous System: Central nervous system (CNS) disease in HIV-infected clients can be divided into intracerebral space–occupying lesions, encephalopathy, meningitis, and spinal cord processes. Toxoplasmosis is the most common space–occupying lesion in HIV-infected clients. Presenting symptoms may include headache, focal neurologic deficits, seizures, or altered mental status. Structural and inflammatory abnormalities in the muscles of people with HIV have been reported to impair the muscle’s ability to extract or utilize oxygen during exercise. Clinical manifestations of HIV-associated myopathies include proximal weakness, myalgia, abnormal electromyogram (EMG) activity, elevated creatine kinase, and decreased functioning of the muscle.25 Peripheral Nervous System: Peripheral nerve disease is a common complication of the HIV infection. Peripheral nervous system syndromes include inflammatory polyneuropathies, sensory neuropathies, and mononeuropathies. An inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy similar to Guillain-Barré syndrome can occur in HIV-infected clients. Cytomegalovirus (CMV), a highly host-specific herpes virus that infects the nerve roots, may result in an ascending polyradiculopathy characterized by lower extremity weakness progressing to flaccid paralysis. Allergy and Atopy: Allergy refers to the abnormal hypersensitivity that takes place when a foreign substance (allergen) is introduced into the body of a person likely to have allergies. The body fights these invaders by producing the special antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE). This antibody (now a vital diagnostic sign of many allergies), when released into the blood, breaks down mast cells, which contain chemical mediators, such as histamine, that cause dilation of blood vessels and the characteristic symptoms of allergy. Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Clinical signs and symptoms vary from one client to another according to the allergies present. With the Family/Personal History form used, each client should be asked what known allergies are present and what the specific reaction to the allergen would be for that particular person. The therapist can then be alert to any of these warning signs during treatment and can take necessary measures, whether that means grading exercise to the client’s tolerance, controlling the room temperature, or appropriately using medications prescribed. Anaphylaxis: Anaphylaxis, the most dramatic and devastating form of type I hypersensitivity, is the systemic manifestation of immediate hypersensitivity. The implicated antigen is often introduced parenterally such as by injection of penicillin or a bee sting. The activation and breakdown of mast cells systematically cause vasodilation and increased capillary permeability, which promote fluid loss into the interstitial space, resulting in the clinical picture of bronchospasms, urticaria (wheals or hives), and anaphylactic shock. Initial manifestations of anaphylaxis may include local itching, edema, and sneezing. These seemingly innocuous problems are followed in minutes by wheezing, dyspnea, cyanosis, and circulatory shock. Clinical signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis are listed by system in Table 12-1. TABLE 12-1 Clinical Aspects of Anaphylaxis by System Modified from Adkinson NF: Middleton’s allergy: principles and practice, ed 7, St. Louis, 2008, Mosby. Manifestations of a transfusion reaction result from intravascular hemolysis of RBCs. Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a noninflammatory condition appearing with generalized musculoskeletal pain in conjunction with tenderness to touch in a large number of specific areas of the body and a wide array of associated symptoms. FMS is much more common in women than in men; it is 2 to 5 times more common than RA. It occurs in age groups from preadolescents to early postmenopausal women.26 The condition is less common in older adults. There is still much controversy over the exact nature of FMS and even debate over whether fibromyalgia is an organic disease with abnormal biochemical or immunologic pathologic aspects. Some theories suggest that it is a genetically predisposed condition with dysregulation of the neurohormonal and autonomic nervous systems.27 It may be triggered by viral infection, a traumatic event, or stress. The role of inadequate thyroid hormone regulation as a main mechanism of fibromyalgia has been proposed and is under investigation.28 Functional brain imaging shows areas of the brain that light up when pressure is applied to painful areas of the body. All indications are that once the central pain mechanisms get turned on, they “wind up” until there is pain even when the stimulus (e.g., pressure, heat, cold, electrical impulses) is no longer there. This phenomenon is called sensory augmentation. There is some evidence that people with fibromyalgia have a decrease in their reactivity threshold. In other words, with a low threshold, it only takes a small amount of stimuli before the pain switch gets turned on. Exactly why this happens remains unknown.27 Controversy also existed regarding use of the American College of Rheumatism (ACR) criteria for tender point count in clinical diagnosis of FMS.29 In fact, the original author of the ACR criteria suggested that counting the tender points was “perhaps a mistake” and advised against using it in clinical practice.30 A Symptom Intensity Scale was subsequently developed and validated by Wolfe31,32 to help differentiate FMS from other rheumatologic conditions (e.g., SLE or polymyalgia rheumatica) with similar widespread pain. Since that time, Wolfe and associates proposed a new set of diagnostic criteria, which the ACR has adopted.33 The new tool focuses on measuring symptom severity rather than relying on the tender point examination. The new criteria use a clinician-queried checklist of painful sites and a symptom severity scale that focuses on fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and sleep disturbance. Tender point assessment still has value; people with fewer than 11 of the 18 tender points included in the ACR classification criteria may still be diagnosed with fibromyalgia if they have other clinical features consistent with fibromyalgia.34 The hallmark of myofascial pain syndrome is the TrP, as opposed to tender points in FMS. Both disorders cause myalgia with aching pain and tenderness and exhibit similar local histologic changes in the muscle. Painful symptoms in both conditions are increased with activity, although fibromyalgia involves more generalized aching, whereas myofascial pain is more direct and localized (Table 12-2). TABLE 12-2 Differentiating Myofascial Pain Syndrome from Fibromyalgia Syndrome Data from Lowe JC, Yellin JG: The metabolic treatment of fibromyalgia, Utica, Kentucky, 2000, McDowell Publications. There is some clinical evidence that myofascial pain syndrome is linked with the use of hormones containing synthetic progestin (e.g., birth control pills). The effects of progestin on women with fibromyalgia is unknown.35 FMS has striking similarities to chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), with a mix of overlapping symptoms (about 70%) that have some common biologic denominator. Diagnostic criteria for CFS focus on fatigue, whereas the criteria for FMS focus on pain, the two most prominent symptoms of these syndromes. Studies have shown that CFS and FMS are characterized by greater similarities than differences and both involve the central and peripheral nervous systems as well as the body tissues themselves (Box 12-2).36 Risk Factors: Numerous studies have implicated a genetic predisposition related to brain and/or body chemistry, but it has also been shown that a history of childhood trauma, family issues, and/or physical/sexual abuse are significant risk factors.37 Stress, illness, disease, or anything the body perceives as a threat are risk factors for those who develop FMS. But why one person develops this condition, whereas others with equal or worse situations do not, remains a mystery. Anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder also seem to be linked with FMS.38 Having a bipolar illness increases the risk of developing FMS dramatically.39 Clinical Signs and Symptoms: The core features of FMS include widespread pain lasting more than 3 months and widespread local tenderness in all clients (Fig. 12-3). Primary musculoskeletal symptoms most frequently reported are (1) aches and pains, (2) stiffness, (3) swelling in soft tissue, (4) tender points, and (5) muscle spasms or nodules. Fatigue, morning stiffness, and sleep disturbance with nonrefreshed awakening may be present but are not necessary for the diagnosis.40 Nontender control points (such as midforehead and anterior thigh) have been included in the examination by some clinicians. These control points may be useful in distinguishing FMS from a conversion reaction, referred to as psychogenic rheumatism, in which tenderness may be present everywhere. However, evidence suggests that individuals with FMS may have a generalized lowered threshold for pain on palpation and the control points may also be tender on occasion. There is also an increased sensitivity to sensory stimulation such as pressure stimuli, heat, noise, odors, and bright lights.41 Symptoms are aggravated by cold, stress, excessive or no exercise, and physical activity (“overdoing it”), including overstretching, and may be improved by warmth or heat, rest, and exercise, including gentle stretching. Smoking has been linked with increased pain intensity and more severe fibromyalgia symptoms, but not necessarily a higher number of tender points. Exposure to tobacco products may be a risk factor for the development of fibromyalgia, but this has not been investigated fully or proven.42 Sleep disturbances in stage 4 of nonrapid eye movement sleep (needed for healing of muscle tissues), sleep apnea, difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep, nocturnal myoclonus (involuntary arm and leg jerks), and bruxism (teeth grinding) cause clients with FMS to wake up, feeling unrested or unrefreshed, as if they had never gone to sleep (Box 12-3). Researchers are beginning to identify various subtypes of fibromyalgia and recognize the need for specific intervention based on the underlying subtype. These classifications are based on impairment of the autonomic nervous system. They include the following35,43: Risk Factors: The etiologic factor or trigger for this process is as yet unknown. Support for a genetic predisposition comes from studies suggesting that RA clusters in families. One gene in particular (HLA-DRB1 on chromosome 6) has been identified in determining susceptibility. RA may be caused by a genetically susceptible person encountering an unidentified agent (e.g., virus, self-antigen), which then results in an immunopathologic response.44 Researchers hypothesize that an infection could trigger an immune reaction that is mediated through multiple complex genetic mechanisms and continues clinically even if the organism is eradicated from the body. Other nongenetic factors may also contribute to the development of RA. Because arthritis (and many related diseases) is more common in women, hormones have been implicated, but the relationship remains unclear. Environmental and occupational causes, such as chemicals (e.g., hair dyes, industrial pollutants), minerals, mineral oil, organic solvents, silica, toxins, medications, food allergies, cigarette smoking, and stress, remain under investigation as possible triggers for those individuals who are genetically susceptible to RA.45 Many systemic disorders can express themselves through the musculoskeletal system often presenting first with rheumatic manifestations (Box 12-4).46 Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Clinical features of RA vary not only from person to person but also in an individual over the disease course. In most people, the symptoms begin gradually during a period of weeks or months. Frequently, malaise and fatigue prevail during this period, sometimes accompanied by diffuse musculoskeletal pain. The multidimensional aspects of rheumatoid arthritic pain can be assessed quantitatively using the Rheumatoid Arthritis Pain Scale (RAPS).47 The complete RAPS is available in the appendix of this article. Studies have shown that 70% to 90% of persons with RA have significant joint erosions on x-ray by only 2 years after disease onset and that halting or slowing erosions should be initiated very early on in the course of the disease.48 Having awareness of the group of symptoms that suggest inflammatory arthritis is critical. It is recommended that the criteria for referral of a person with early inflammatory symptoms include significant discomfort on the compression of the metacarpal and metatarsal joints, the presence of three or more swollen joints, and more than 1 hour of morning stiffness.49 Shoulder: Chronic synovitis of the elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, and/or ankles creates special secondary disorders. When the shoulder is involved, limitation of shoulder mobility, dislocation, and spontaneous tears of the rotator cuff result in chronic pain and adhesive capsulitis. Elbow: Destruction of the elbow articulations can lead to flexion contracture, loss of supination and pronation, and subluxation. Compressive ulnar nerve neuropathies may develop related to elbow synovitis. Symptoms include paresthesias of the fourth and fifth fingers and weakness in the flexor muscle of the little finger. Wrists: The joints of the wrist are frequently affected in RA, with variable tenosynovitis of the dorsa of the wrists and, ultimately, interosseous muscle atrophy and diminished movement owing to articular destruction or bony ankylosis. Volar synovitis can lead to carpal tunnel syndrome. Hands and Feet: Forefoot pain may be the only small-joint complaint and is often the first one. Subluxation of the heads of the MTP joints and shortening of the extensor tendons give rise to “hammer toe” or “cock up” deformities. A similar process in the hands results in volar subluxation of the MCP joints and ulnar deviation of the fingers. An exaggerated inflammatory response of an extensor tendon can result in a spontaneous, often asymptomatic rupture. Hyperextension of a proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint and flexion of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint produce a swan neck deformity. The boutonnière deformity is a fixed flexion contracture of a PIP joint and extension of a DIP joint.

Screening for Immunologic Disease

Using the Screening Model

Past Medical History

Clinical Presentation

Review of Systems

Immune System Pathophysiology

Immunodeficiency Disorders

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

AIDS and Other Diseases

Hypersensitivity Disorders

Type I Anaphylactic Hypersensitivity (“Allergies”)

Type II Hypersensitivity (Cytolytic or Cytotoxic)

Autoimmune Disorders

Fibromyalgia Syndrome

Myofascial Pain Syndrome

Fibromyalgia Syndrome

Trigger points (pain with deep pressure); often radiates locally

Tender points (pain with light touch); no radiation

Localized musculoskeletal condition

Systemic condition

Palpable taut band found in muscle; no associated signs and symptoms

No palpable or visible local abnormality; wide array of associated signs and symptoms

Etiology: Overuse, repetitive motions; reduced muscle activity (e.g., casting or prolonged splinting); hormones containing progestins (under investigation)35

Etiology: Neurohormonal imbalance; autonomic nervous system dysfunction

Risk factors: Immobilization, repetitive use

Risk factors: Trauma, psychosocial stress, mood (or other psychologic) disorders; other medical conditions

Pathophysiology: Unknown, possibly muscle spindle dysfunction

Pathophysiology: Sensitization of spinal neurons from excitatory nerve messenger substances

Prognosis: Excellent

Prognosis: Good with early diagnosis and intervention, variable with delayed diagnosis; often a chronic condition

Rheumatoid Arthritis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree