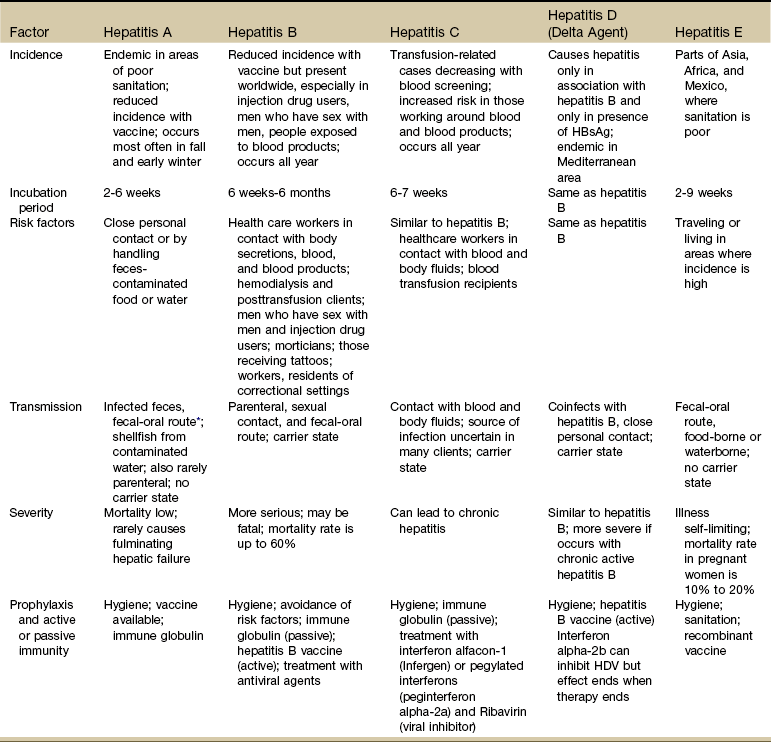

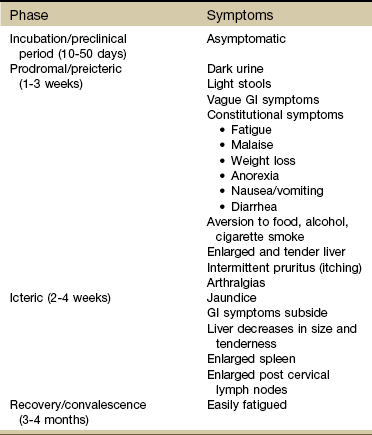

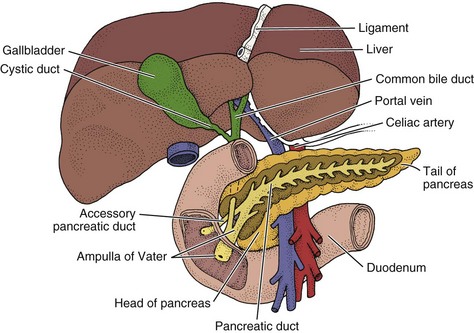

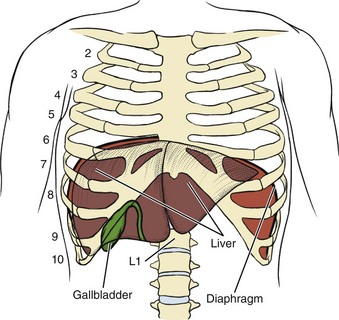

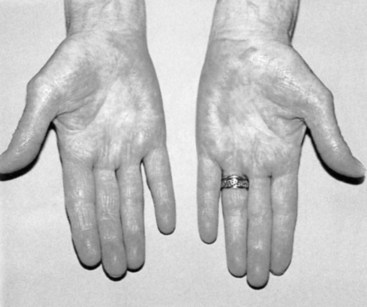

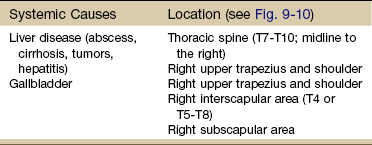

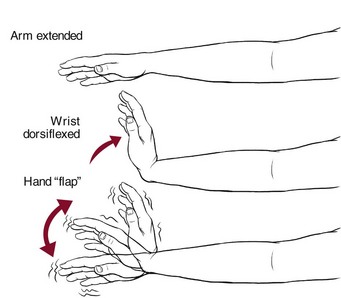

Chapter 9 As with many of the organ systems in the human body, the hepatic and biliary organs (liver, gallbladder, and common bile duct) can develop diseases that mimic primary musculoskeletal lesions (Fig. 9-1). The musculoskeletal symptoms associated with hepatic and biliary pathologic conditions are generally confined to the mid-back, scapular, and right shoulder regions. These musculoskeletal symptoms can occur alone (as the only presenting symptom) or in combination with other systemic signs and symptoms discussed in this chapter. Taking a careful history and making close observations of the client’s physical condition and appearance can detect telltale signs of hepatic disease. Most of the liver is contained underneath the rib cage and is largely inaccessible (Fig. 9-2). An enlarged liver that is palpable is always a red flag (see Fig. 4-51). Medical diagnosis of liver or gallbladder disease is made by x-ray examination or ultrasonic scanning of the gallbladder and computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen, including the liver. Other skin changes may include pruritus (itching), bruising, spider angiomas (Fig. 9-3), and palmar erythema (see Fig. 9-5). Spider angiomas (arterial spider, spider telangiectasis, vascular spider), branched dilations of the superficial capillaries resembling a spider in appearance (Fig. 9-4), may be vascular manifestations of increased estrogen levels (hyperestrogenism). Spider angiomas and palmar erythema both occur in the presence of liver impairment as a result of increased estrogen levels normally detoxified by the liver. Palmar erythema (warm redness of the skin over the palms, also called liver palms), caused by an extensive collection of arteriovenous anastomoses, is especially evident on the hypothenar and thenar eminences and pulps of the finger (Fig. 9-5). The person may complain of throbbing, tingling palms. The soles of the feet may be similarly affected. Throbbing and tingling may be associated with these anastomoses. Various forms of nail disease have been described in cases of liver impairment such as the white nails of Terry (Fig. 9-6). Other nail bed changes, such as white bands across the nail plate (leukonychia), clubbed nails (see Fig. 4-36), or koilonychia (see Fig. 4-32), can occur, but these are not specific to liver impairment and can develop in the presence of other diseases as well. Musculoskeletal pain associated with the hepatic and biliary systems includes thoracic pain between the scapulae, right shoulder, right upper trapezius, right interscapular, or right subscapular areas (see Fig. 9-10 and Table 9-1). Referred shoulder pain may be the only presenting symptom of hepatic or biliary disease. Afferent pain signals from the superior ligaments of the liver and the superior portion of the liver capsule are transmitted by the phrenic nerves. Sympathetic fibers from the biliary system are connected through the celiac (abdominal) and splanchnic (visceral) plexuses to the hepatic fibers in the region of the dorsal spine (see Fig. 3-3). The celiac and splanchnic connections account for the intercostal and radiating interscapular pain that accompanies gallbladder disease. Although the innervation is bilateral, most of the biliary fibers reach the cord through the right splanchnic nerves, synapsing with adjacent phrenic nerve fibers innervating the diaphragm and producing pain in the right shoulder (see Fig. 3-4). Hepatic osteodystrophy, abnormal development of bone, can occur in all forms of cholestasis (bile flow suppression) and hepatocellular disease, especially in the alcoholic person. Either osteomalacia or more often, osteoporosis frequently accompanies bone pain from this condition. Vertebral wedging, vertebral crush fractures, and kyphosis can be severe; decalcification of the ribcage and pseudofractures1 occur frequently. Osteoporosis associated with primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis parallels the severity of liver disease rather than its duration. Painful osteoarthropathy may develop in the wrists and ankles as a nonspecific complication of chronic liver disease. Rhabdomyolysis is a potentially fatal condition is which myoglobin and other muscle tissue contents are released into the bloodstream as a result of muscle tissue disintegration. This could occur with acute trauma (e.g., crush injuries, significant blunt trauma, high-voltage electrical burns, surgery2), severe burns, overexertion,3 or in the case of liver impairment, from alcohol abuse or alcohol poisoning or the use of cholesterol-lowering drugs called statins (e.g., Zocor, Lipitor, Crestor, Mevacor, Pravachol).4 Rhabdomyolysis is characterized by muscle aches, cramps, soreness, and weakness. It may be accompanied by other symptoms of respiratory muscle myopathy (impaired diaphragmatic function)5 or liver or renal involvement. Laboratory testing will show a creatine kinase (CK) level more than 10 times the upper limit of normal. Although the literature reports the incidence of this severe myopathy with statin use as about 0.1% to 2.0% in clinical trials,6 therapists (and others) report seeing cases more often than the low percentage would suggest. Any anatomic region can be affected, but the back and extremity musculoskeletal pain are the two areas of involvement reported most often.7,8 Statin-associated myopathy appears to occur more often in people with complex medical problems and/or those taking illegal drugs (e.g., cocaine, heroin, LSD) or abusing prescription drugs (e.g., barbiturates and amphetamines).9 Other risk factors that increase the chances of this condition include excessive alcohol use, advancing age (over 80 years), recent history of surgery, and small physical stature.4 For additional discussion, see Screening for Side Effects of Statins in Chapter 6. Another outward sign of liver disease producing CNS dysfunction is asterixis. Impaired inflow of joint and other afferent information to the brainstem reticular formation produces this movement dysfunction. Also called flapping tremors or liver flap, asterixis is described as the inability to maintain wrist extension with forward flexion of the upper extremities. It is tested by asking the client to actively hyperextend the wrist and hand with the rest of the arm supported on a firm surface or with the arms held out in front of the body (Fig. 9-7).10 The test is positive if quick, irregular extensions and flexions of the wrist and fingers occur. Asterixis may also be observed when releasing the pressure in the arm cuff during blood pressure readings. Fig. 9-7 To test for asterixis or liver flap, have the client extend the arms, spread the fingers, extend the wrist, and observe for the abnormal “flapping” tremor at the wrist. If a tremor is not readily apparent, ask the client to keep the arms straight while gently hyperextending the client’s wrist. There is an alternate method of testing for this phenomenon: have the client relax the legs in the supine position with the knees bent. The feet are flat on the table. As the legs fall to the sides, watch for a flapping or tremoring of the legs at the hip. The knees appear to come back toward the midline repeatedly.10 Asterixis and numbness/tingling (the latter are misinterpreted as carpal tunnel syndrome) can occur as a result of this ammonia abnormality, causing an intrinsic nerve pathologic condition (Case Example 9-1). There are many potential causes of carpal tunnel syndrome, both musculoskeletal and systemic (see Table 11-2). Careful evaluation is required (Box 9-1). Viral Hepatitis: Viral hepatitis is an acute infectious inflammation of the liver caused by one of the following identified viruses: A, B, C, D, E, and G (Table 9-2). TABLE 9-2 Comparison of Major Types of Viral Hepatitis HBsAg, Hepatitis B surface antigen; HDV, hepatitis D virus. *The oral-fecal route of transmission is primarily from poor or improper handwashing and personal hygiene, particularly after using the bathroom and then handling food for public consumption. This route of transmission may also occur through shared use of razors and oral utensils such as straws, silverware, and toothbrushes. From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Division of Viral Hepatitis. Viral Hepatitis for Health Professionals. Available online at www.cdc.gov/hepatitis. Accessed Oct. 18, 2010. Viral hepatitis is spread easily to others and usually results in an extended period of convalescence with loss of time from school or work. It is estimated that 60% to 90% of viral hepatitis cases are unreported because many cases are subclinical or involve mild symptoms.11,12 Hepatitis A and E are transmitted primarily by the fecal-oral route. Common source outbreaks result from contaminated food or water. Hepatitis A virus (HAV) must also be considered a potential problem in situations where fecal-oral communication along with food handling and/or unsanitary conditions occur. Some examples of potential sources of contact with HAV might include restaurants, day care centers, correctional institutions, sewage plants, and countries where these viruses are endemic.13,14 Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is usually transmitted by inoculation of infected blood or blood products or by sexual contact and is also found in body fluids (e.g., spinal, peritoneal, pleural), saliva, semen, and vaginal secretions. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) must have HBV present to coinfect. Groups at risk include homosexuals and intravenous (IV) drug users; health care workers in any area in which contact with blood, blood products, or body fluids is likely; and residents and workers in correctional settings.14,15 Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted similarly to HBV and HDV. Risk factors are also very similar with the addition of people who have received blood transfusions or organ transplants, including anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction allograft.16,17 There has been growing concern worldwide about the risk of occupational transmission of HCV. Occupational exposure to HCV accounts for approximately 4% of new infections. On average, the chance of acquiring HCV after a needle-stick injury involving an infected patient is 1.8% (range, 0% to 7%). Reports of HCV transmission from health care workers to patients are extremely uncommon.14 Hepatitis G virus (HGV) designation has been applied to a virus that is percutaneously transmitted and associated with bloodborne viral presence lasting approximately 10 years. HGV has been detected primarily in IV drug users, clients on hemodialysis, clients with hemophilia, and in a small percentage of blood donors. It does not appear to cause important liver disease or affect the response rate of those with chronic HBV or HCV to antiviral therapy.18 Hepatitis affects people in three stages: the initial or preicteric stage, the icteric or jaundiced stage, and the recovery period (Table 9-3). During the initial or preicteric stage, which lasts for 1 to 3 weeks, the person experiences vague gastrointestinal (GI) and general body symptoms. Fatigue, malaise, lassitude, weight loss, and anorexia are common. TABLE 9-3 Four Phases or Stages of Hepatitis Source: World Health Organization. Global alert and response to hepatitis. Available online at www.who.int. Accessed February 1, 2011. Modified from Goodman CC, Fuller KS: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2009, WB Saunders. Many people develop an aversion to food, alcohol, and cigarette smoke. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, arthralgias, and influenza-like symptoms may occur. There is a strong association between hepatitis-induced arthralgia and age with increasing incidence of joint involvement with increased age; arthralgia in children is much less common.19,20 The liver becomes enlarged and tender (see Fig. 4-51), and intermittent itching (pruritus) may develop. From 1 to 14 days before the icteric stage, the urine darkens and the stool lightens as less bilirubin is conjugated and excreted. The icteric (acute) stage is characterized by the appearance of jaundice, which peaks in 1 to 2 weeks and can persist for 6 to 8 weeks. During this stage, the acuteness of the inflammation subsides. The GI symptoms begin to disappear, and after 1 to 2 weeks of jaundice the liver decreases in size and becomes less tender. During the icteric stage the post-cervical lymph nodes and spleen are enlarged (see Fig. 4-53). Persons who have been treated with human immune serum globulin (ISG) may not develop jaundice. An entire spectrum of rheumatic diseases can occur concomitantly with HBV and HBC, including transient arthralgias, vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), fibromyalgia, lymphoma, Sjögren’s syndrome, and persistent synovitis. Some conditions, such as RA and fibromyalgia, occur only in association with HCV, whereas others, such as polyarteritis nodosa, are observed in association with both forms of hepatitis.20–22 Rheumatic manifestations of hepatitis are varied early in the course of disease and can be indistinguishable from mild RA. The therapist should be suspicious of anyone with risk factors for hepatitis, including injection drug use; previous blood transfusion, especially before 1991; hemodialysis; or other exposure to blood products/body fluids, such as a health care worker (Box 9-2), or a past history of hepatitis that currently appears with arthralgias (Case Example 9-2). Chronic Hepatitis: Chronic hepatitis is the term used to describe an illness associated with prolonged inflammation of the liver after unresolved viral hepatitis or associated with chronic active hepatitis (CAH) of unknown cause. Chronic is defined as inflammation of the liver for 6 months or more. The symptoms and biochemical abnormalities may continue for months or years. It is divided into CAH and chronic persistent hepatitis (CPH) by findings on liver biopsy. Chronic Active Hepatitis: This type of hepatitis refers to seriously destructive liver disease that can result in cirrhosis. CAH is often a result of viral infection (HBV, HCV, and HDV), but it can also be secondary to drug sensitivity (e.g., methyldopa [Aldomet], an antihypertensive medication, and isoniazid [INH], an antitubercular drug). Conventional IFN has been used for many years in the treatment of chronic HCV in clients who persistently maintain HCV/RNA blood levels. Combining IFNs with the drug ribavirin has resulted in better control of chronic HCV in some individuals, but the treatment is not well tolerated because of side effects from the ribavirin.23,24 Pegylated IFNs, such as Pegasys (peginterferon alpha-2a), are improved forms of IFNs that allow a decrease in dosage and offer improved efficacy. Peginterferons (PEGs) in combination with ribavirin are now considered the standard treatment for chronic HCV infection. These new PEG interferons do not eliminate the known side effects associated with classical interferon treatment (e.g., fatigue, headache, myalgia, fever, anxiety, irritability, GI upset).19,25

Screening for Hepatic and Biliary Disease

Hepatic and Biliary Signs and Symptoms

Skin and Nail Bed Changes

Musculoskeletal Pain

Neurologic Symptoms

Hepatic and Biliary Pathophysiology

Hepatitis