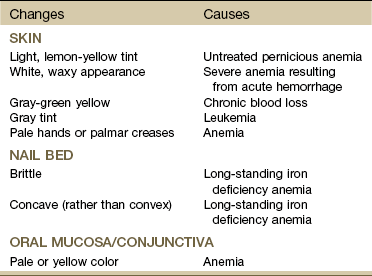

Chapter 5 Primary hematologic diseases are uncommon, but hematologic manifestations secondary to other diseases are common. Cancers of the blood are discussed in Chapter 13. Hematologic considerations in the orthopedic population fall into two main categories: bleeding and clotting. People with known abnormalities of hemostasis (either hypocoagulation or hypercoagulation problems) will require close observation.1 There are many signs and symptoms that can be associated with hematologic disorders. Some of the most important indicators of dysfunction in this system include problems associated with exertion (often minimal exertion) such as dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, severe weakness, and fatigue. Neurologic symptoms, such as headache, drowsiness, dizziness, syncope, or polyneuropathy, can also indicate a variety of possible problems in this system.2,3 Significant skin and fingernail bed changes that can occur with hematologic problems might include pallor of the face, hands, nail beds, and lips; cyanosis or clubbing of the fingernail beds; and wounds or easy bruising or bleeding in skin, gums, or mucous membranes, often with no reported trauma to the area. The presence of blood in the stool or emesis or severe pain and swelling in joints and muscles should also alert the physical therapist to the possibility of a hematologic-based systemic disorder and can sometimes be a critical indicator of bleeding disorders that can be life threatening.2,3 Many hematologic-induced signs and symptoms seen in the physical therapy practice occur as a result of medications. For example, chronic or long-term use of steroids and NSAIDs can lead to gastritis and peptic ulcer with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and subsequent iron deficiency anemia.4 Leukopenia, a common problem occurring during chemotherapy, or as a symptom of certain types of cancer, can produce symptoms of infections such as fever, chills, tissue inflammation; severe mouth, throat and esophageal pain; and mucous membrane ulcerations.5 • Anemia (too few erythrocytes) • Polycythemia (too many erythrocytes) • Poikilocytosis (abnormally shaped erythrocytes) • Anisocytosis (abnormal variations in size of erythrocytes) Anemia is a reduction in the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood as a result of an abnormality in the quantity or quality of erythrocytes. Anemia is not a disease but is a symptom of any number of different blood disorders. Excessive blood loss, increased destruction of erythrocytes, and decreased production of erythrocytes are the most common causes of anemia.6 1. Iron deficiency associated with chronic GI blood loss secondary to NSAID use 2. Chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, kidney disease, liver disease) or inflammatory diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus) 3. Neurologic conditions (pernicious anemia) 4. Infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and neoplastic disease or cancer (bone marrow failure). Anemia with neoplasia may be a common complication of chemotherapy or develop as a consequence of bone marrow metastasis.7 Anemia can also occur as a symptom of leukemia. Adults with pernicious anemia have significantly higher risks for hip fracture even with vitamin B12 therapy. The hypothesized underlying factor is a lack of gastric acid (achlorhydria).8 Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Deficiency in the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood may result in disturbances in the function of many organs and tissues leading to various symptoms that differ from one person to another. Slowly developing anemia in young, otherwise healthy individuals is well tolerated, and there may be no symptoms until hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit fall below one half of normal (see values inside book cover). Changes in the hands and fingernail beds (Table 5-1) may be observed during the inspection/observation portion of the physical therapy evaluation (see Table 4-8 and Boxes 4-13 and 4-15). The physical therapist should look for pale palms with normal-colored creases (severe anemia causes pale creases as well). Observation of the hands should be done at the level of the client’s heart. In addition, the anemic client’s hands should be warm; if they are cold, the paleness is due to vasoconstriction. Systolic blood pressure may not be affected, but diastolic pressure may be lower than normal, with an associated increase in the resting pulse rate. Resting cardiac output is usually normal in people with anemia, but cardiac output increases with exercise more than it does in people without anemia.9 As the anemia becomes more severe, resting cardiac output increases and exercise tolerance progressively decreases until dyspnea, tachycardia, and palpitations occur at rest. Diminished exercise tolerance is expected in the client with anemia. Exercise testing and prescribed exercise(s) in clients with anemia must be instituted with extreme caution and should proceed very gradually to tolerance and/or perceived exertion levels.10,11 In addition, exercise for any anemic client should be first approved by his or her physician (Case Example 5-1). Clinical Signs and Symptoms: The symptoms of this disease are often insidious in onset with vague complaints. The most common first symptoms are shortness of breath and fatigue. The affected individual may be diagnosed only secondary to a sudden complication (e.g., stroke or thrombosis). Increased skin coloration and elevated blood pressure may develop as a result of the increased concentration of erythrocytes and increased blood viscosity. Watch for increase in blood pressure and elevated hematocrit levels. Sickle cell disease is a generic term for a group of inherited, autosomal recessive disorders characterized by the presence of an abnormal form of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying constituent of erythrocytes. A genetic mutation resulting in a single amino acid substitution in hemoglobin causes the hemoglobin to aggregate into long chains, altering the shape of the cell. This sickled or curved shape causes the cell to lose its ability to deform and squeeze through tiny blood vessels, thereby depriving tissue of an adequate blood supply.3 Clinical Signs and Symptoms: A series of “crises,” or acute manifestations of symptoms, characterize sickle cell disease. Some people with this disease have only a few symptoms, whereas others are affected severely and have a short lifespan. Recurrent episodes of vasoocclusion and inflammation result in progressive damage to most organs, including the brain, kidneys, lungs, bones, and cardiovascular system, which becomes apparent with increasing age. Cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) and cognitive impairment are a frequent and severe manifestation.16 Stress from viral or bacterial infection, hypoxia, dehydration, emotional disturbance, extreme temperatures, fever, strenuous physical exertion, or fatigue may precipitate a crisis. Pain caused by the blockage of sickled RBCs forming sickle cell clots is the most common symptom; it may be in any organ, bone, or joint of the body. Painful episodes of ischemic tissue damage may last 5 or 6 days and manifest in many different ways, depending on the location of the blood clot (Case Example 5-2).

Screening for Hematologic Disease

Signs and Symptoms of Hematologic Disorders

Classification of Blood Disorders

Anemia

Polycythemia

Sickle Cell Anemia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree