Left untreated, scapholunate dissociation can lead to posttraumatic wrist arthritis. Multiple surgical procedures have been designed to reduce the scapholunate interval, restore normal wrist kinematics, and prevent the development of arthritis. Unfortunately, current surgical procedures have not been shown to consistently maintain radiographic alignment at long-term follow-up and result in decreased wrist range of motion and strength compared with the contralateral side. The purpose of this article is to review the current reconstructive options for scapholunate ligament tears without evidence of radiographic arthritis.

Key points

- •

Left untreated, scapholunate (SL) ligament tears can result in a predictable pattern of radiocarpal arthritis, termed SL advanced collapse ( SLAC ).

- •

SL reconstruction is indicated in symptomatic patients without evidence of radiocarpal arthritis. Patients with established radiocarpal arthritis may be better served with a salvage procedure.

- •

Most current treatments have not been shown to reliably maintain reduction of the SL interval and SL angle at long-term follow-up.

- •

Currently there is no consensus on the optimal treatment method for patients with SL ligament tears.

- •

Several new treatment methods for SL ligament tears have been developed but need further clinical evaluation.

Introduction

The SL interosseous ligament (SLIL) is an important structure for maintaining normal carpal alignment and kinematics. SL instability can be defined as a wrist that exhibits abnormal kinematics with motion and is symptomatic during weight-bearing activities and normal arc of motion. Untreated, SL instability leads to a predictable pattern of radiocarpal arthritis referred to as SLAC. The decision to repair or reconstruct the SLIL is predicated on the absence of radiocarpal arthritis. Patients with evidence of established radiocarpal arthritis are better treated with salvage procedures. Ideally, an orthopedic surgeon can intervene and prevent the development of an SLAC wrist. The purpose of this article is to review the reconstructive treatment options for SL instability.

Epidemiology

The SLIL is the most commonly injured intercarpal ligament and it results in the most frequent pattern of carpal instability. The prevalence of this injury is likely underestimated because it is commonly missed on initial presentation. Cadaveric studies have found tears in approximately one-third of wrists in elderly patients, many with no history of wrist injury. These tears may represent a combination of acute and degenerative tears. In a clinical study, Jones reviewed 100 cases of wrist injuries in which a sprained wrist was the initial diagnosis. Subsequently, a clenched fist radiograph was preformed and 19 of 100 patients had an increase in the SL interval. Significant SL instability was ultimately diagnosed in 5 patients. Intercarpal ligamentous injuries are also common in association with distal radius fractures and scaphoid fractures. SL ligament tears have been reported to occur in as high as 54% of displaced distal radius fractures and instability can be seen in as many as 21.5% of cases. Jorgsholm and colleagues found SL ligament injuries in approximately 50% of scaphoid waist fractures and complete disruption in 24%. These findings point to the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion when treating patients with wrist injuries.

Anatomy

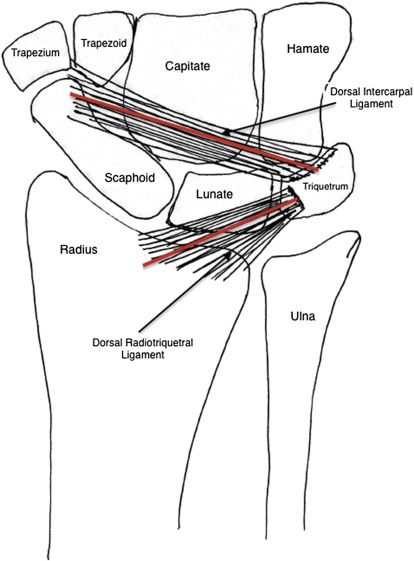

The wrist joint is kinematically one of the most complex joints in the body. In actuality, it is the summation of several smaller joints, including the articulations between the carpals bones, radius, ulna, and metacarpals. It can be conceptually simplified into the distal row (trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate), proximal row (scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum), and the surrounding articulations. The distal row is tightly bound by strong intercarpal ligaments with little motion between its constituents. The bones of the proximal row functionally are intercalary pieces because there are no tendinous insertions on them and their motion depends on their articulations, with the surrounding intrinsic and extrinsic ligaments restricting their motion. The SLIL is one of these intrinsic ligaments. It is C-shaped, running between the dorsal, volar, and proximal thirds of the bones. It is generally subdivided based on anatomic location. The dorsal portion is the most robust and strongest, comprised primarily of collagen. It is the primary restraint to distraction, torsion, and translation. The volar portion is also collagenous but thin and provides primarily rotational control. The proximal portion is comprised of fibrocartilage and is grossly membranous with little restraint to motion. Several extrinsic ligaments function as secondary stabilizers and their disruption in isolation do not cause frank SL instability. Important volar ligaments are the radioscaphocapitate ligament, radiolunate ligaments, and the radioscapholunate ligament. Dorsally the dorsal intercarpal ligament and dorsal radiotriquetral ligament assist in SL stabilization.

Mechanism of Injury

Injury to the SLIL usually occurs with stress loading of extended carpus. It can occur with a fall onto an outstretched hand or with higher-energy trauma. The theorized mechanism for injury during a fall on an outstretched hand is wrist extension, intercarpal supination, and ulnar deviation, which cause failure of the SLIL. In severe hyperextension, the injury continues causing, in succession, tears of the radiocapitate, radiotriquetral, and dorsal radiocarpal ligaments. The lunate then falls into extension by virtue of is attachment to triquetrum, and dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) deformity occurs.

When the SLIL is injured, there is variable presentation based on the severity of the injury to the secondary stabilizing ligaments and surrounding soft tissues. Left unchecked this instability can progress in a stepwise succession to frank arthritis. Determination of the stage of SL instability is important because it can guide treatment. Geissler and colleagues proposed a method to quantify SL injury by arthroscopic assessment with a probe. In grade I injury there is attenuation but no step-off. Grade II injuries have attenuation with incongruency between the scaphoid and lunate. Grades III and IV injuries have complete SLIL disruption but in grade III a 1-mm probe passes through the SL interval and in grade IV a 2.7-mm probe passes through.

The least severe presentation of SL instability is termed occult instability . In this pattern there is either a tear or attenuation of the SL ligament but generally no radiographic findings, even with stress radiographs. The only hint is pain with mechanical loading or painful clunks. The next step in progression occurs when patients have normal static radiographs but abnormal stress radiographs. These patients have dynamic instability and have subtotal or complete SL disruptions with partial disruption of the secondary stabilizers. An anteroposterior (AP) grip film with 2 to 3 mm of increased gapping compared with the contralateral wrist, is suggestive of SL insufficiency. Lateral full flexion radiographs show an SL angle greater than 60% and subluxation of the proximal pole of the scaphoid to contact the volar articular surface of the radius. Radial and ulnar deviation films may also show SL widening.

After dynamic instability is static instability in which there are abnormal static radiographs. These patients have complete disruption of the SLIL and 1 or more of the secondary stabilizing ligaments. Cadaveric studies have recognized the dorsal intercarpal (DIC) ligament as one of the most important stabilizing ligaments, allowing palmar subluxation of the lunate. As the motions of the scaphoid and lunate are uncoupled, they rotate in opposite directions. The scaphoid rotates into increased flexion as the SL gap increases. The lunate extends with mechanical loading due to the dorsally directed force of the capitate. With time, abnormal motion becomes a deformity and static radiographs are abnormal, termed DISI with fixed flexion of the scaphoid and extension of the lunate and triquetrum . The distal carpal row translates proximally and dorsally. When a patient has demonstrated DISI deformity, soft tissue procedure alone is ineffective due to attenuation and degeneration of secondary stabilizers as well as surrounding soft tissue envelope. The abnormal kinematics of the wrist lead to degenerative changes found in SLAC wrists. Watson and colleagues described the sequential arthritic evolution of an SLAC wrist in 1984. Initially the degenerative changes are limited to the articulation between the tip of the radial styloid and radial aspect of the distal pole of the scaphoid. Next they involve the entire radioscaphoid articulation. Later the changes progress to the capitolunate joint due to abnormal articular wear as the capitate migrates proximally between the capitate and lunate.

In general, reconstructive options are indicated in cases of SL dissociation without evidence of degenerative changes.

Introduction

The SL interosseous ligament (SLIL) is an important structure for maintaining normal carpal alignment and kinematics. SL instability can be defined as a wrist that exhibits abnormal kinematics with motion and is symptomatic during weight-bearing activities and normal arc of motion. Untreated, SL instability leads to a predictable pattern of radiocarpal arthritis referred to as SLAC. The decision to repair or reconstruct the SLIL is predicated on the absence of radiocarpal arthritis. Patients with evidence of established radiocarpal arthritis are better treated with salvage procedures. Ideally, an orthopedic surgeon can intervene and prevent the development of an SLAC wrist. The purpose of this article is to review the reconstructive treatment options for SL instability.

Epidemiology

The SLIL is the most commonly injured intercarpal ligament and it results in the most frequent pattern of carpal instability. The prevalence of this injury is likely underestimated because it is commonly missed on initial presentation. Cadaveric studies have found tears in approximately one-third of wrists in elderly patients, many with no history of wrist injury. These tears may represent a combination of acute and degenerative tears. In a clinical study, Jones reviewed 100 cases of wrist injuries in which a sprained wrist was the initial diagnosis. Subsequently, a clenched fist radiograph was preformed and 19 of 100 patients had an increase in the SL interval. Significant SL instability was ultimately diagnosed in 5 patients. Intercarpal ligamentous injuries are also common in association with distal radius fractures and scaphoid fractures. SL ligament tears have been reported to occur in as high as 54% of displaced distal radius fractures and instability can be seen in as many as 21.5% of cases. Jorgsholm and colleagues found SL ligament injuries in approximately 50% of scaphoid waist fractures and complete disruption in 24%. These findings point to the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion when treating patients with wrist injuries.

Anatomy

The wrist joint is kinematically one of the most complex joints in the body. In actuality, it is the summation of several smaller joints, including the articulations between the carpals bones, radius, ulna, and metacarpals. It can be conceptually simplified into the distal row (trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate), proximal row (scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum), and the surrounding articulations. The distal row is tightly bound by strong intercarpal ligaments with little motion between its constituents. The bones of the proximal row functionally are intercalary pieces because there are no tendinous insertions on them and their motion depends on their articulations, with the surrounding intrinsic and extrinsic ligaments restricting their motion. The SLIL is one of these intrinsic ligaments. It is C-shaped, running between the dorsal, volar, and proximal thirds of the bones. It is generally subdivided based on anatomic location. The dorsal portion is the most robust and strongest, comprised primarily of collagen. It is the primary restraint to distraction, torsion, and translation. The volar portion is also collagenous but thin and provides primarily rotational control. The proximal portion is comprised of fibrocartilage and is grossly membranous with little restraint to motion. Several extrinsic ligaments function as secondary stabilizers and their disruption in isolation do not cause frank SL instability. Important volar ligaments are the radioscaphocapitate ligament, radiolunate ligaments, and the radioscapholunate ligament. Dorsally the dorsal intercarpal ligament and dorsal radiotriquetral ligament assist in SL stabilization.

Mechanism of Injury

Injury to the SLIL usually occurs with stress loading of extended carpus. It can occur with a fall onto an outstretched hand or with higher-energy trauma. The theorized mechanism for injury during a fall on an outstretched hand is wrist extension, intercarpal supination, and ulnar deviation, which cause failure of the SLIL. In severe hyperextension, the injury continues causing, in succession, tears of the radiocapitate, radiotriquetral, and dorsal radiocarpal ligaments. The lunate then falls into extension by virtue of is attachment to triquetrum, and dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) deformity occurs.

When the SLIL is injured, there is variable presentation based on the severity of the injury to the secondary stabilizing ligaments and surrounding soft tissues. Left unchecked this instability can progress in a stepwise succession to frank arthritis. Determination of the stage of SL instability is important because it can guide treatment. Geissler and colleagues proposed a method to quantify SL injury by arthroscopic assessment with a probe. In grade I injury there is attenuation but no step-off. Grade II injuries have attenuation with incongruency between the scaphoid and lunate. Grades III and IV injuries have complete SLIL disruption but in grade III a 1-mm probe passes through the SL interval and in grade IV a 2.7-mm probe passes through.

The least severe presentation of SL instability is termed occult instability . In this pattern there is either a tear or attenuation of the SL ligament but generally no radiographic findings, even with stress radiographs. The only hint is pain with mechanical loading or painful clunks. The next step in progression occurs when patients have normal static radiographs but abnormal stress radiographs. These patients have dynamic instability and have subtotal or complete SL disruptions with partial disruption of the secondary stabilizers. An anteroposterior (AP) grip film with 2 to 3 mm of increased gapping compared with the contralateral wrist, is suggestive of SL insufficiency. Lateral full flexion radiographs show an SL angle greater than 60% and subluxation of the proximal pole of the scaphoid to contact the volar articular surface of the radius. Radial and ulnar deviation films may also show SL widening.

After dynamic instability is static instability in which there are abnormal static radiographs. These patients have complete disruption of the SLIL and 1 or more of the secondary stabilizing ligaments. Cadaveric studies have recognized the dorsal intercarpal (DIC) ligament as one of the most important stabilizing ligaments, allowing palmar subluxation of the lunate. As the motions of the scaphoid and lunate are uncoupled, they rotate in opposite directions. The scaphoid rotates into increased flexion as the SL gap increases. The lunate extends with mechanical loading due to the dorsally directed force of the capitate. With time, abnormal motion becomes a deformity and static radiographs are abnormal, termed DISI with fixed flexion of the scaphoid and extension of the lunate and triquetrum . The distal carpal row translates proximally and dorsally. When a patient has demonstrated DISI deformity, soft tissue procedure alone is ineffective due to attenuation and degeneration of secondary stabilizers as well as surrounding soft tissue envelope. The abnormal kinematics of the wrist lead to degenerative changes found in SLAC wrists. Watson and colleagues described the sequential arthritic evolution of an SLAC wrist in 1984. Initially the degenerative changes are limited to the articulation between the tip of the radial styloid and radial aspect of the distal pole of the scaphoid. Next they involve the entire radioscaphoid articulation. Later the changes progress to the capitolunate joint due to abnormal articular wear as the capitate migrates proximally between the capitate and lunate.

In general, reconstructive options are indicated in cases of SL dissociation without evidence of degenerative changes.

Treatment

Capsulodesis

Acute surgical intervention is believed to improve outcomes with the goal of intervening before arthritic changes have set in. Capsulodesis is designed is to reinforce the extrinsic ligaments. Unfortunately, the procedure often sacrifices postoperative flexion. It is indicated in both chronic and subacute settings. It was classically described without SL ligament repair; however, when possible, a ligamentous repair should be done. Since the original description by Blatt in 1987, multiple modifications have been described. Blatt capsulodesis was designed to limit palmar flexion of the scaphoid. It involves a straight dorsal capsulotomy, raising a radially-based capsular flap that is left attached to the radius. The scaphoid and lunate are reduced using Kirschner (K) wires as joysticks and the flap is then attached to the distal pole of the scaphoid via a bony trough and tied over a button. The scaphoid is pinned to the capitate for 3 months. Short-term outcomes showed good symptomatic relief and patient satisfaction rates of 58%. There was, however, poor restoration of normal carpal relationships, in particular SL widening, and some patients developed SLAC wrists requiring further surgery.

Several investigators have described combining the capsulodesis with suture and anchors repairing the SLIL. Lavernia and colleagues evaluated 21 patients at an average follow-up of 33 months and found 11° loss of palmar flexion and similar grip strength to the contralateral side. Approximately 50% patients reported that wrist function still interfered with activities. The SL angle improved from 62° to 57° degrees and SL gap reduced from 3.2 mm to 1.9 mm. Uhl and colleagues examined 35 patients at an average of 36 months finding an average loss of 15° flexion and 85% recovery of grip strength. A majority of patients (25/35) returned to their preinjury job. The SL gap recurred in all patients but the investigators noted that radiographic recurrence of the SL gap did not correlate with symptoms. Pomerance evaluated 17 patients at an average follow-up of 66 months. Grip strength was 82% percent of the uninjured wrist and all patients reporting continued pain with activity (1 severe, 7 moderate, and 7 mild). SL angle on average progressed from 49° preoperatively to 54° at follow-up and 3 developed an SLAC wrist. The investigators noted that at long-term follow-up, initial clinical and radiographic gains deteriorated, especially in patients with a strenuous occupation.

Berger and colleagues described a capsular-sparing approach in which the dorsal radiocarpal and DIC ligaments are split, creating a flap with the apex at the triquetrum ( Fig. 1 ). To perform the capsulodesis (Mayo capsulodesis [MC]), the proximal strip of the flap is attached to dorsal lunate after the lunate is derotated from extension to a neutral position and held in place with K-wires. Moran conducted a retrospective review of 31 patients, at a mean follow-up of 54 months, who were treated with either a Blatt capsulodesis or MC. The investigators noted an average loss of wrist flexion of 20° and no improvement in grip strength after surgery. Pain was minimal or none in approximately 60% of patients, but more than 20% of patients continued to complain of severe pain with activities of daily living. Although the preoperative SL gap was corrected from 2.7 mm to 1.7 mm, the mean SL gap at final follow-up was 3.9 mm. The study did not analyze differences between the Blatt capsulodesis and MC techniques. Wyrick and colleagues reviewed 17 patients at mean follow-up of 30 months and found that no patients were pain-free and radiographic improvements obtained at the time of surgery were not maintained. The mean SL angle preoperatively was 78°and the final mean SL angle was 72°. Mean total wrist arc of motion was only 60% of the contralateral side and mean grip strength was 70% of the contralateral side.