Essentials of Diagnosis

- Systemic disease due to noncaseating epithelioid granulomatous inflammation in affected organs.

- Most frequently affected organs are lung, lymph nodes, eyes, skin, joints, liver, muscles, central and peripheral nervous system, upper airway, heart, and kidneys.

- Clinically apparent organ involvement is typically restricted to a few organs, usually defined early in the course of disease.

- In the United States, sarcoidosis is more common and severe in blacks.

- Diagnosis requires a compatible clinical picture and a biopsy with typical noncaseating granulomas, excluding diseases that can cause similar granulomatous reactions.

General Considerations

Sarcoidosis is found worldwide with a prevalence ranging from 10 to 80 cases per 100,000 in North America and Europe. Higher regional prevalence has been reported in Scandinavia and the southeast coastal United States. In the United States, one study from a Midwest city estimated that the lifetime risk of developing sarcoidosis was 2.7% in black women, 2.1% in black men, 1% in white women, and 0.8% in white men. Worldwide, there is a slight female predominance. Although all ages can be affected, most cases occur between the ages of 20 and 40 years, with a second peak incidence in women over age 60.

A genetic predisposition to sarcoidosis is supported by familial clustering in approximately 5–10% of cases of sarcoidosis. A recent multicenter study on the etiology of sarcoidosis in the United States (A Case-Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis [ACCESS]) suggests that the familial relative risk is approximately 5.0 among first-degree relatives, and this risk is higher in white families compared with black families.

The strongest associations between genotype and sarcoidosis risk have been identified within the major histocompatibility (MHC) locus on chromosome 6. Two recent genome-wide linkage analyses identified an association with the butyrophilin-like 2 gene (BTNL2) (located within the MHC locus) in both whites and blacks with sarcoidosis.

The cause of sarcoidosis is uncertain. The genetic pattern of inheritance suggests that susceptibility to sarcoidosis is polygenic and interacts importantly with environmental factors. Geographic differences in disease prevalence and reports of time-space clustering of cases have also suggested that sarcoidosis may be associated with an environmental, likely microbial, exposure. The large, multicenter study ACCESS found no evidence for a single dominant environmental or occupational exposure associated with an increased risk of developing sarcoidosis. Multiple regression analyses found positive associations with modest odds ratios of approximately 1.5 for exposures to molds and mildews, insecticides, or musty odors at work. The ACCESS data supported a negative association of tobacco use or tobacco smoke exposure among sarcoidosis patients.

Since the first description of sarcoidosis, many experts have speculated that a potential microbial cause of sarcoidosis exists. Recent studies using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have associated mycobacterial and propionibacterial organisms as possible etiologic factors for sarcoidosis. A recent meta-analysis concluded that 26% of sarcoidosis tissues contained mycobacterial nucleic acids, with an odds-ratio of 9- to 19-fold higher chance of finding mycobacterial nucleic acids in sarcoidosis compared with control tissues. Recently, a limited proteomic approach identified the mycobacterial catalase-peroxidase protein (mKatG) as a candidate pathogenic antigen. This and other studies from the United States and Europe have demonstrated immunologic responses to mKatG and other mycobacterial proteins in a subgroup of sarcoidosis patients, supporting a mycobacterial etiology of sarcoidosis. In Japan, a subgroup of sarcoidosis patients has been demonstrated to have immunologic responses to Propionibacterium acnes. No studies have demonstrated the presence of live organisms from sarcoidosis tissues, distinguishing sarcoidosis from active infections. How these microbial organisms trigger sarcoidosis remains unknown.

There are certain immunologic hallmarks of sarcoidosis regardless of the potential etiologic trigger. There is usually an accumulation of CD4+ dominant T cell infiltration at sites of granulomatous inflammation, with fewer CD8+ T cells usually surrounding the granulomas. These CD4+ T cells have biased expression of specific T cell receptor genes, consistent with oligoclonal expansion of antigen-specific T cells. The antigen-specific T cell response is highly polarized toward a T helper 1 response with expression of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and the Th1 immunomodulatory cytokines, interleukin-12 (IL-12), and IL-18. Along with Th1 cytokines, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-1, IL-6, and a Th1-associated chemokines together orchestrate the local granulomatous response. Dysregulated expression of Th1 immunomodulatory cytokines has been hypothesized to central to the development of granulomatous inflammation in sarcoidosis.

Clinical Findings

There is tremendous heterogeneity in the clinical manifestations of sarcoidosis. Pulmonary involvement is documented in >90% of patients. Nonpulmonary manifestations are present in many patients with or without pulmonary involvement (Table 54–1).

| Clinically Evident Organ System Involvement (%) | Major Clinical Features |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary (70–90%) | Bilateral hilar adenopathy, restrictive and obstructive disease, reticulonodular infiltrates, fibrocystic disease, bronchiectasis, mycetomas |

| Ocular (20–30%) | Anterior and posterior uveitis, optic neuritis, chorioretinitis, conjunctival nodules, glaucoma, keratoconjunctivitis, lacrimal gland enlargement |

| Cutaneous (20–30%) | Erythema nodosum, lupus pernio, cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules, plaques, alopecia, dactylitis |

| Hematologic (20–30%) | Peripheral lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hypersplenism, anemia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia |

| Musculoskeletal/joints (10–20%) | Arthralgias, bone cysts, myopathy, heel pain, Achilles tendinitis, sacroiliitis |

| Hepatic (10–20%) | Hepatomegaly, pruritus, jaundice, cirrhosis |

| Salivary and parotid gland (10%) | Sicca syndrome, Heerfordt syndrome |

| Neurologic (5–15%) | Cranial neuropathy, aseptic meningitis, mass brain lesion, hydrocephalus, myelopathy, polyneuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex |

| Sinuses and upper respiratory tract (5–10%) | Chronic sinusitis, nasal congestion, saddle-nose deformity, hoarseness, laryngeal or tracheal obstruction |

| Cardiac (5–10%) | Arrhythmias, heart block, cardiomyopathy, sudden death |

| Gastrointestinal (<10%) | Abdominal pain, gastrointestinal tract dysmotility, pancreatitis |

| Endocrine (<10%) | Hypercalcemia, hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus, epididymitis, testicular mass |

| Renal (<10%) | Interstitial nephritis, glomerulonephritis, nephrolithiasis, hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis |

An initial diagnostic evaluation should consist of tests to evaluate the presence and extent of pulmonary involvement and screening for common extrathoracic involvement (Table 54–2). Specialized testing is indicated when symptoms or signs suggest extrapulmonary involvement.

|

This syndrome of acute sarcoidosis is characterized by erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar adenopathy, and often polyarthritis and uveitis (Figure 54–1). Löfgren syndrome is common among Scandinavians and Irish women but occurs in less than 5% of black patients with sarcoidosis. Acute sarcoidosis without erythema nodosum may also occur, often with disabling arthritis.

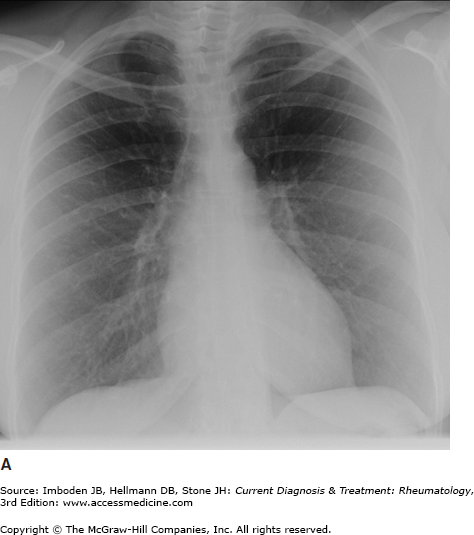

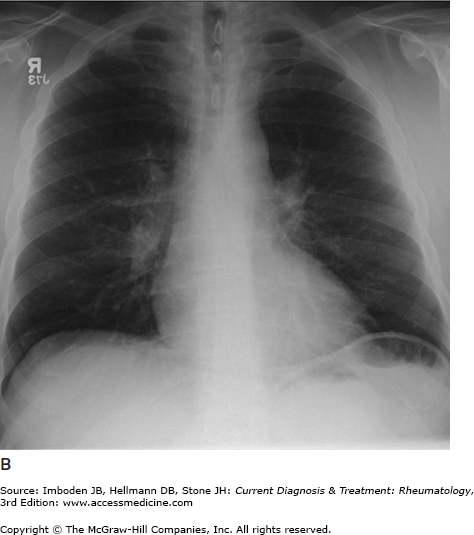

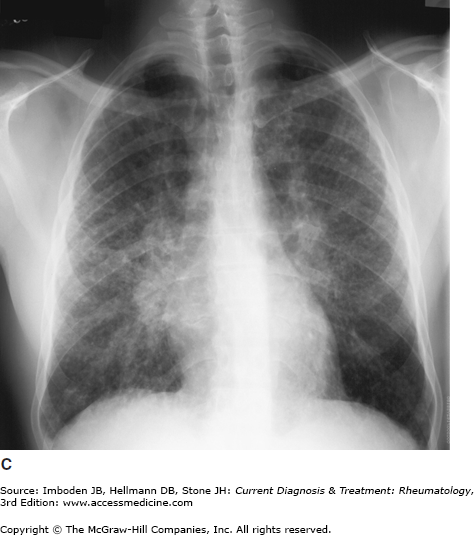

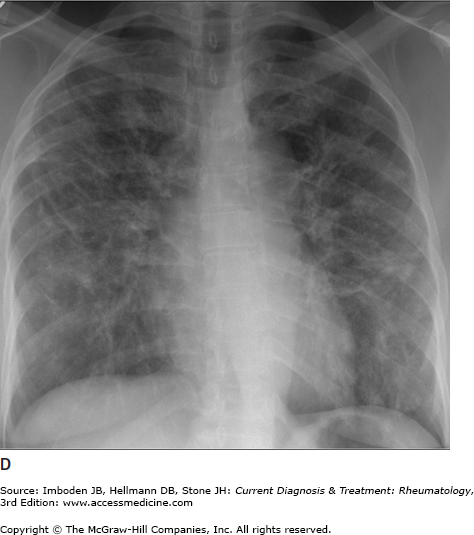

Figure 54–1.

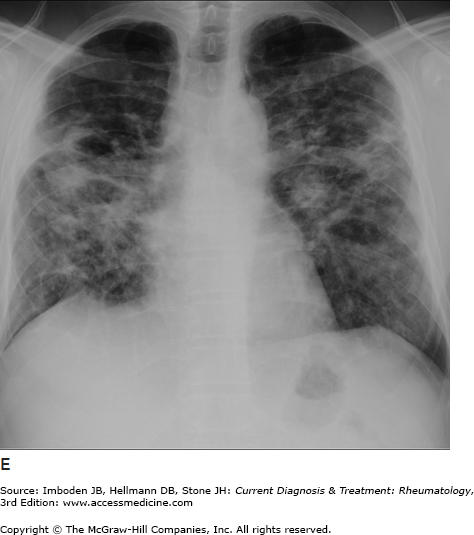

Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Posteroanterior chest radiographs illustrating pulmonary sarcoidosis categorized as stage 0 (normal chest film), stage I (bilateral hilar adenopathy alone), stage II (adenopathy plus interstitial infiltrates), stage III (interstitial infiltrates alone), and stage IV (fibrocystic). Thoracic disease (lung and lymph node involvement) represent the most common manifestations of sarcoidosis affecting over 70% of all patients. Bronchscopy remains the most common method of confirming a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

The most common symptoms are progressive shortness of breath, nonproductive cough, and chest discomfort (Table 54–1). Chronic sputum production and hemoptysis are more frequent in advanced fibrocystic disease (chest radiograph stage IV, Figure 54–1). Typically, there are few physical findings of pulmonary sarcoidosis, with lung crackles heard in less than 10% of patients. Clubbing is rare. Airway obstruction is usually fixed (unresponsive to bronchodilators) and observed in a minority of patients. Bronchial hyperreactivity with occasional frank wheezing is found in 5–30% of patients.

Pulmonary hypertension or cor pulmonale is seen in >80% patients with advanced fibrocystic sarcoidosis with pulmonary fibrosis. Rarely, a granulomatous pulmonary vasculitis results in pulmonary hypertension with little evidence of interstitial lung disease. Dyspnea out of proportion to pulmonary function test results should prompt a search for pulmonary hypertension. Other causes of pulmonary hypertension, such as sleep disordered breathing or chronic thromboembolic disease, must be excluded. Severe pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced lung disease is associated with higher rates of mortality while awaiting lung transplantation.

Uveitis is the most common eye lesion in sarcoidosis and may be the initial presenting manifestation. The uveitis is more commonly anterior, may be unilateral or bilateral, and is frequently associated with bilateral hilar adenopathy. Chronic uveitis occurs in as many as 20% of patients with chronic sarcoidosis and is more common in the black population. Granulomatous conjunctivitis appears as a granular or cobblestone-like appearance of the conjunctivae. Conjunctival nodules are also a common finding. Optic neuritis or retinitis may manifest dramatically with blindness. Severe chorioretinitis occurs uncommonly.

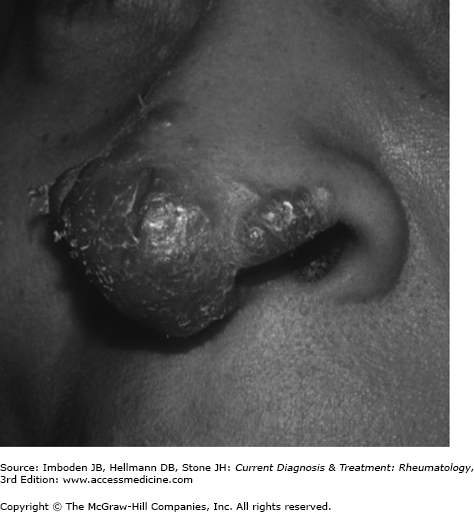

Sarcoidosis commonly involves the skin (20–30%) and may be severe, especially in black patients. Cutaneous nodules, plaques and subcutaneous nodules, typically located around the hairline, eyelids, ears, nose, mouth, and extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, are common. Lupus pernio is a particularly disfiguring form of cutaneous sarcoidosis of the face with violaceous plaques and nodules covering the nose (Figure 54–2), nasal alae, malar areas, and around the eyes.

Peripheral lymph node enlargement occurs in 20–30% of patients as an early manifestation of sarcoidosis but then typically undergoes spontaneous remission. Persistent, bulky lymphadenopathy occurs less than 10% of the time. Splenomegaly, occasionally massive, occurs in less than 5% of cases and is often associated with hepatomegaly and hypercalcemia. Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia is present in 25% or more of patients. Anemia and peripheral lymphopenia are relatively common while leucopenia and thrombocytopenia are rare. A clinical association exists between sarcoidosis and common variable immunodeficiency (CVID); CVID should be suspected in patients with sarcoidosis who develop increased frequency of infections or hypogammaglobulinemia.

Systemic constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, and weight loss are seen in over 20% of patients and may be disabling. Arthralgias are common in active multisystem sarcoidosis, although joint radiographs are usually normal. Acute, often incapacitating polyarthritis involving the ankles, feet, knees, and wrists is commonly seen in patients with Löfgren syndrome; usually the polyarthritis regresses within weeks to several months with or without therapy. Persistent joint disease is found in less than 5% of patients with chronic sarcoidosis. Pain, swelling, and tenderness of the phalanges (sausage digit) of the hands and feet are most common.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree